Hands-On Gets a Thumbs Up

Changing the Way Schools Teach STEM

“I was really happy every time I came to school this week.” That was the reaction of a Boston public school student to the inaugural Boston STEM week, which ran from October 3rd through 7th, 2016.

And why not? Instead of the usual curriculum for the more than 6,000 students in Boston’s 36 middle schools, kids were building lunar colonies, creating interactive monsters, designing digital games, or isolating their DNA and practicing surgical techniques.

It was hands-on learning. Engaging. Empowering. As Marjorie Soto, principal of the Hurley K-8 Dual Language School in Boston’s South End put it, “I saw kids who were wearing goggles and lab coats, working with the human heart to see how the blood goes through it."

"They were able to make connections and inferences based on what they saw, and connect it to what they had read. They not only experienced this learning, they owned it. It was as if they had become immersed in an exciting problem-solving community. For my sixth, seventh, and eighth graders, STEM Week was like finding the entry point into their heart and soul.”

Boston STEM Week was created by the team at i2 Learning. The company’s founder, Ethan Berman, was inspired to bring immersive, hands-on STEM learning to middle school students by the experience of his nine-year-old daughter who liked school well enough, but who really liked solving problems and making things with her own hands, especially, as she put it, “if it was something useful.”

“What if schools could offer a different approach to STEM education that would provide these kinds of immersive learning opportunities?” Berman wondered. That “what if” evolved into a program that would capture the imaginations of the city’s population of middle schoolers, as well as parents, educators, politicians, curriculum partners from the world’s leading STEM organizations, and a broad range of community and corporate sponsors.

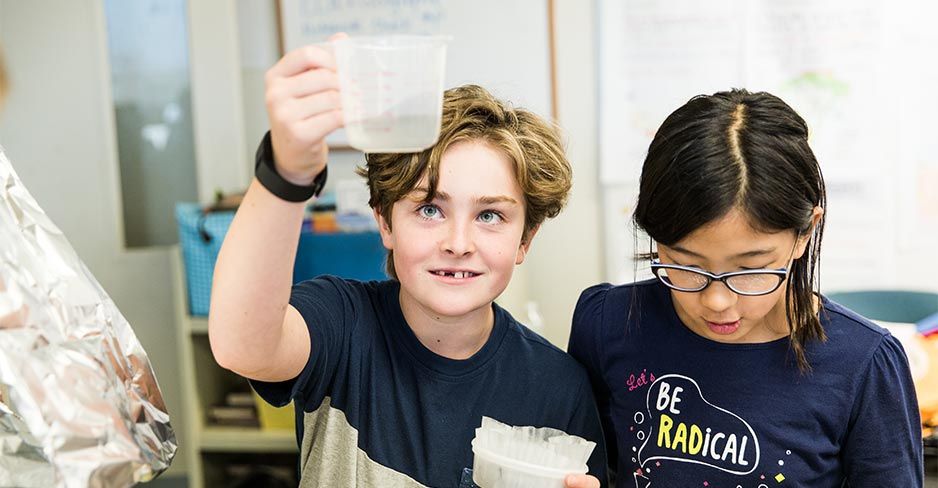

Image courtesy of i2 Learning

The initial week-long STEM program was so successful that it was held in Boston’s middle schools again in 2017. In addition, five schools are participating in a pilot program that replaces their traditional sixth grade coursework for an entire month. Using a special curriculum co-developed with MIT that expands the Building a Lunar Colony learning module, these sixth graders will read and write science fiction, discover space exploration, and develop their own form of government in addition to constructing a sustainable colony.

i2 focused on middle school students because research showed that this was the age at which boys and girls started to lose interest in science and math. “Our theory was if you change the way these subjects are taught, you can change that perception,” said Berman.

The program’s curriculum is based on the engineering design process; this iterative process teaches that it’s okay to make mistakes as long as one is willing to learn from them. According to Phil Thornton, school liaison at i2, “There are an awful lot of kids these days who are pretty risk-averse.They actually don’t want to start something until they have a pretty good idea that they’re on the right path.” Instead, students in the STEM Week program are encouraged to give something a try and, if it doesn’t work, sit down and think about how it could have been better; then take another shot at it.

So how did the i2 team persuade the Boston School system to give up their regular school curriculum and try this innovative learning approach? “We’d already run a couple of successful pilot programs,” said Thornton. “Boston School officials had seen the program in action and were impressed, so we made them a proposal: we would run a one-week STEM Week program in every middle school in the city, at no cost to the school. We would raise the money, train the teachers, handle all the logistics, and provide all the materials and equipment.”

“It sounds like a no-brainer, but it was a big ask,” said Berman. “There aren’t many systems that would cancel all their classes and put their entire middle school on a STEM curriculum. It was a combination of first, having seen the program in action as a pilot; second, the sponsorship of organizations like MathWorks, MIT, and the Lynch and Boston Foundations; and third, having a school department that was willing to take a chance.”

Adds Thornton, “There were also bright, courageous innovators in the school system. We went directly to the school leaders and teachers and told them about the benefits of STEM Week. They were so open to the possibilities. So many of them told us, after our initial conversation, ‘You know, this is the way I believe middle school should be’.”

Image Courtesy of i2 Learning

That’s not to say there wasn’t some apprehension going into the program. As sixth-grade English Language Arts teacher Helen Sullivan put it, “I was excited about the interdisciplinary aspect of STEM Week—it’s the educator’s dream—but it made me a little nervous from the teaching point of view.” To address this concern, i2 had all 300 Boston middle school teachers participate in a two-day professional development workshop. After personally experiencing the project-based activities and strategies she would later use in the classroom, Sullivan became a believer.

Of course, it’s in the classrooms where the true test of this approach to STEM education takes place. Research conducted by The Center for Technology and School Change (CTSC) at Teachers College, Columbia University revealed significant differences in student perceptions pre- and post-STEM Week, including increased interest in STEM-related subjects and classes, increased comfort in working on projects, and increased interest in STEM-related careers.

Ross Wilson, the Chief Innovation Officer for the Boston Public Schools at the time, believes the rich, project-based STEM curriculum provided the schools with a spark experience. “Our teachers could connect to that learning over the course of the entire school year, and the applied learning approach helped the abstract become real, so students who typically struggled in math tended to do well.”

“It is not an overstatement to say that this type of learning environment has the potential to change the trajectory of young people’s lives. There was a sense of excitement, an atmosphere of accomplishment. The kids were so excited to show off their learning.”

In one school, a student with learning disabilities completed a brain dissection, all by himself. His teachers were stunned. At Rose’s school, a student who had been struggling with literacy gained enough coding proficiency over the course of the week that he created a digital game so challenging, no one could get through it. Rose was thrilled for the boy, “Now, he has a success that he can revisit and draw from when faced with other challenges.”

Rose recalled watching one of his 7th graders demonstrate his digital monster to a kindergartener. “The boy had learned enough coding to get the monster to light up, and the younger kid was just full of questions that the older boy was patiently explaining and answering.”

Parents noticed the changes as well. The mother of one eight-grader was brimming with enthusiasm, “My daughter was rarely excited about anything that happened in school. With STEM Week, she came home every day, saying ‘Ma, guess what!’ She was very proud of herself; she was engaged; she was speaking in class; she even wants to sign up for some of the new STEM-related electives they’re offering. I just wish the school had been doing this all along. I’m so happy. She’s so happy!”

As STEM Week evolves into STEM month, Berman and Thornton are thinking about getting the idea in to as many schools in the city as possible. “We’re thinking about what we call i2 month,” says Berman, “because it’s not just STEM; then maybe a conversation about doing a semester.”

Image Courtesy of i2 Learning

Marjorie Soto is already way ahead of them; she saw how STEM Week changed her students. “It stayed with them for the rest of the school year,” she says, “Kids walked a little taller, listened a little bit harder. I could see them imagining their own future.”

“I want this program to start in the fifth grade,” she says, “and I want it to last all year.”