Mixed-Integer Quadratic Programming Portfolio Optimization: Problem-Based

This example shows how to solve a Mixed-Integer Quadratic Programming (MIQP) portfolio optimization problem using the problem-based approach. The idea is to iteratively solve a sequence of mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problems that locally approximate the MIQP problem. For the solver-based approach, see Mixed-Integer Quadratic Programming Portfolio Optimization: Solver-Based.

Problem Outline

As Markowitz showed ("Portfolio Selection," J. Finance Volume 7, Issue 1, pp. 77-91, March 1952), you can express many portfolio optimization problems as quadratic programming problems. Suppose that you have a set of N assets and want to choose a portfolio, with being the fraction of your investment that is in asset . If you know the vector of mean returns of each asset, and the covariance matrix of the returns, then for a given level of risk-aversion you maximize the risk-adjusted expected return:

The quadprog solver addresses this quadratic programming problem. However, in addition to the plain quadratic programming problem, you might want to restrict a portfolio in a variety of ways, such as:

Having no more than

Massets in the portfolio, whereM <= N.Having at least

massets in the portfolio, where0 < m <= M.Having semicontinuous constraints, meaning either , or for some fixed fractions and .

You cannot include these constraints in quadprog. The difficulty is the discrete nature of the constraints. Furthermore, while the mixed-integer linear programming solver does handle discrete constraints, it does not address quadratic objective functions.

This example constructs a sequence of MILP problems that satisfy the constraints, and that increasingly approximate the quadratic objective function. While this technique works for this example, it might not apply to different problem or constraint types.

Begin by modeling the constraints.

Modeling Discrete Constraints

is the vector of asset allocation fractions, with for each . To model the number of assets in the portfolio, you need indicator variables such that when , and when . To get variables that satisfy this restriction, set the vector to be a binary variable, and impose the linear constraints

These inequalities both enforce that and are zero at exactly the same time, and they also enforce that whenever .

Also, to enforce the constraints on the number of assets in the portfolio, impose the linear constraints

Objective and Successive Linear Approximations

As first formulated, you try to maximize the objective function. However, all Optimization Toolbox™ solvers minimize. So formulate the problem as minimizing the negative of the objective:

This objective function is nonlinear. The MILP solver requires a linear objective function. There is a standard technique to reformulate this problem into one with linear objective and nonlinear constraints. Introduce a slack variable to represent the quadratic term.

As you iteratively solve MILP approximations, you include new linear constraints, each of which approximates the nonlinear constraint locally near the current point. In particular, for where is a constant vector and is a variable vector, the first-order Taylor approximation to the constraint is

Replacing by gives

For each intermediate solution you introduce a new linear constraint in and as the linear part of the expression above:

This has the form , where , there is a multiplier for the term, and .

This method of adding new linear constraints to the problem is called a cutting plane method. For details, see J. E. Kelley, Jr. "The Cutting-Plane Method for Solving Convex Programs." J. Soc. Indust. Appl. Math. Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 703-712, December, 1960.

MATLAB® Problem Formulation

To express optimization problems:

Decide what your variables represent

Express lower and upper bounds in these variables

Give linear equality and inequality expressions

Load the data for the problem. This data has 225 expected returns in the vector r and the covariance of the returns in the 225-by-225 matrix Q. The data is the same as in the Using Quadratic Programming on Portfolio Optimization Problems example.

load port5

r = mean_return;

Q = Correlation .* (stdDev_return * stdDev_return');Set the number of assets as N.

N = length(r);

Create Problem Variables, Constraints, and Objective

Create continuous variables xvars representing the asset allocation fraction, binary variables vvars representing whether or not the associated xvars is zero or strictly positive, and zvar representing the variable, a positive scalar.

xvars = optimvar('xvars',N,1,'LowerBound',0,'UpperBound',1); vvars = optimvar('vvars',N,1,'Type','integer','LowerBound',0,'UpperBound',1); zvar = optimvar('zvar',1,'LowerBound',0);

The lower bounds of all the 2N+1 variables in the problem are zero. The upper bounds of the xvars and yvars variables are one, and zvar has no upper bound.

Set the number of assets in the solution to be between 100 and 150. Incorporate this constraint into the problem in the form, namely

by writing two linear constraints:

M = 150; m = 100; qpprob = optimproblem('ObjectiveSense','maximize'); qpprob.Constraints.mconstr = sum(vvars) <= M; qpprob.Constraints.mconstr2 = sum(vvars) >= m;

Include semicontinuous constraints. Take the minimal nonzero fraction of assets to be 0.001 for each asset type, and the maximal fraction to be 0.05.

fmin = 0.001; fmax = 0.05;

Include the inequalities and .

qpprob.Constraints.fmaxconstr = xvars <= fmax*vvars; qpprob.Constraints.fminconstr = fmin*vvars <= xvars;

Include the constraint that the portfolio is 100% invested, meaning .

qpprob.Constraints.allin = sum(xvars) == 1;

Set the risk-aversion coefficient to 100.

lambda = 100;

Define the objective function and include it in the problem.

qpprob.Objective = r'*xvars - lambda*zvar;

Solve the Problem

To solve the problem iteratively, begin by solving the problem with the current constraints, which do not yet reflect any linearization.

options = optimoptions(@intlinprog,'Display','off'); % Suppress iterative display [xLinInt,fval,exitFlagInt,output] = solve(qpprob,'options',options);

Prepare a stopping condition for the iterations: stop when the slack variable is within 0.01% of the true quadratic value.

thediff = 1e-4;

iter = 1; % iteration counter

assets = xLinInt.xvars;

truequadratic = assets'*Q*assets;

zslack = xLinInt.zvar;Keep a history of the computed true quadratic and slack variables for plotting. Set a tighter constraint tolerance than default to help the iterations converge to a correct solution.

history = [truequadratic,zslack]; options.ConstraintTolerance = 1e-9;

Compute the quadratic and slack values. If they differ, then add another linear constraint and solve again.

Each new linear constraint comes from the linear approximation

After you find a new solution, use a linear constraint halfway between the old and new solutions. This heuristic way of including linear constraints can be faster than simply taking the new solution. To use the solution instead of the halfway heuristic, comment the "Midway" line below, and uncomment the following one.

while abs((zslack - truequadratic)/truequadratic) > thediff % relative error constr = 2*assets'*Q*xvars - zvar <= assets'*Q*assets; newname = ['iteration',num2str(iter)]; qpprob.Constraints.(newname) = constr; % Solve the problem with the new constraints [xLinInt,fval,exitFlagInt,output] = solve(qpprob,'options',options); assets = (assets+xLinInt.xvars)/2; % Midway from the previous to the current % assets = xLinInt(xvars); % Use the previous line or this one truequadratic = xLinInt.xvars'*Q*xLinInt.xvars; zslack = xLinInt.zvar; history = [history;truequadratic,zslack]; iter = iter + 1; end

Examine the Solution and Convergence Rate

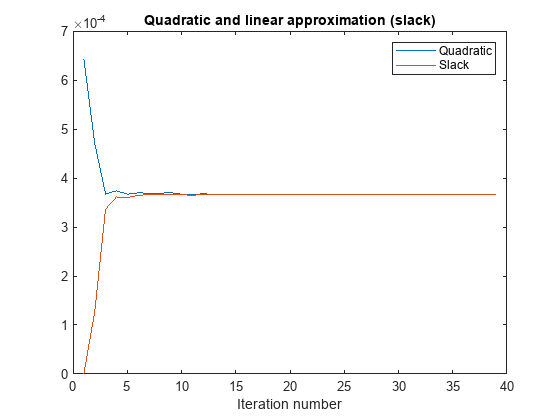

Plot the history of the slack variable and the quadratic part of the objective function to see how they converged.

plot(history) legend('Quadratic','Slack') xlabel('Iteration number') title('Quadratic and linear approximation (slack)')

What is the quality of the MILP solution? The output structure contains that information. Examine the absolute gap between the internally-calculated bounds on the objective at the solution.

disp(output.absolutegap)

0

The absolute gap is zero, indicating that the MILP solution is accurate.

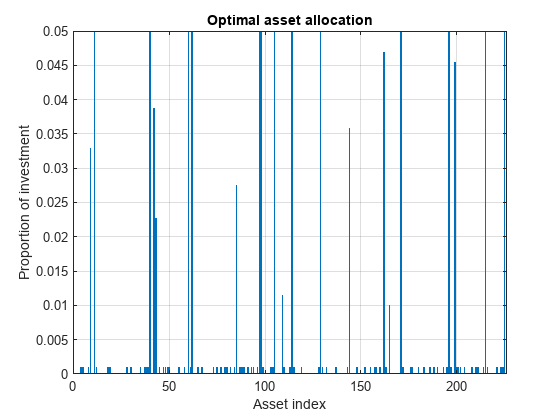

Plot the optimal allocation. Use xLinInt.xvars, not assets, because assets might not satisfy the constraints when using the midway update.

bar(xLinInt.xvars) grid on xlabel('Asset index') ylabel('Proportion of investment') title('Optimal asset allocation')

You can easily see that all nonzero asset allocations are between the semicontinuous bounds and .

How many nonzero assets are there? The constraint is that there are between 100 and 150 nonzero assets.

sum(xLinInt.vvars)

ans = 100

What is the expected return for this allocation, and the value of the risk-adjusted return?

fprintf('The expected return is %g, and the risk-adjusted return is %g.\n',... r'*xLinInt.xvars,fval)

The expected return is 0.000595107, and the risk-adjusted return is -0.0360382.

More elaborate analyses are possible by using features specifically designed for portfolio optimization in Financial Toolbox®. For an example that shows how to use the Portfolio class to directly handle semicontinuous and cardinality constraints, see Portfolio Optimization with Semicontinuous and Cardinality Constraints (Financial Toolbox).