Contenuto principale

Risultati per

The GCD approach to identify rough numbers is a terribly useful one, well worth remembering. But at some point, I expect someone to notice that all work done with these massively large symbolic numbers uses only one of the cores on your computer. And, having spent so much money on those extra cores in your CPU, surely we can find a way to use them all? The problem is, computations done on symbolic integers never use more than 1 core. (Sad, unhappy face.)

In order to use all of the power available to your computer using MATLAB, you need to work in double precision, or perhaps int64 or uint64. To do that, I'll next search for primes among the family 3^n+4. In fact, they seem pretty common, at least if we look at the first few such examples.

F = @(n) sym(3).^n + 4;

F(0:16)

ans =

[5, 7, 13, 31, 85, 247, 733, 2191, 6565, 19687, 59053, 177151, 531445, 1594327, 4782973, 14348911, 43046725]

isprime(F(0:16))

ans =

1×17 logical array

1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

Of the first 11 members of that sequence, 7 of them were prime. Naturally, primes will become less frequent in this sequence as we look further out. The members of this family grow rapidly in size. F(10000) has 4771 decimal digits, and F(100000) has 47712 decimal digits. We certainly don't want to directly test every member of that sequence for primality. However, what I will call a partial or incomplete sieve can greatly decrease the work needed.

Consider there are roughly 5.7 million primes less than 1e8.

numel(primes(1e8))

ans =

5761455

F(17) is the first member of our sequence that exceeds 1e8. So we can start there, since we already know the small-ish primes in this sequence.

roughlim = 1e8;

primes1e8 = primes(roughlim);

primes1e8([1 2]) = []; % F(n) is never divisible by 2 or 3

F_17 = double(F(17));

Fremainders = mod(F_17,primes1e8);

nmax = 100000;

FnIsRough = false(1,nmax);

for n = 17:nmax

if all(Fremainders)

FnIsRough(n) = true;

end

% update the remainders for the next term in the sequence

% This uses the recursion: F(n+1) = 3*F(n) - 8

Fremainders = mod(Fremainders*3 - 8,primes1e8);

end

sum(FnIsRough)

ans =

6876

These will be effectively trial divides, even though we use mod for the purpose. The result is 6876 1e8-rough numbers, far less than that total set of 99984 values for n. One thing of great importance is to recognize this sequence of tests will use an approximately constant time per test regardless of the size of the numbers because each test works off the remainders from the previous one. And that works as long as we can update those remainders in some simple, direct, and efficient fashion. All that matters is the size of the set of primes to test against. Remember, the beauty of this scheme is that while I did what are implicitly trial divides against 5.76 million primes at each step, ALL of the work was done in double precision. That means I used all 8 of the cores on my computer, pushing them as hard as I could. I never had to go into the realm of big integer arithmetic to identify the rough members in that sequence, and by staying in the realm of doubles, MATLAB will automatically use all the cores you have available.

The first 10 values of n (where n is at least 17), such that F(n) is 1e8-rough were

FnIsRough = find(FnIsRough);

FnIsRough(1:10)

ans =

22 30 42 57 87 94 166 174 195 198

How well does the roughness test do to eliminate composite members of this sequence?

isprime(F(FnIsRough(1:10)))

ans =

1×10 logical array

1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1

As you can see, 8 of those first few 1e8-rough members were actually prime, so only 2 of those eventual isprime tests were effectively wasted. That means the roughness test was quite useful indeed as an efficient but relatively weak pre-test for possible primality. More importantly it is a way to quickly eliminate those values which can be known to be composite.

You can apply a similar set of tests on many families of numbers. For example, repunit primes are a great case. A rep-digit number is any number composed of a sequence of only a single digit, like 11, 777, and 9999999999999.

However, you should understand that only rep-digit numbers composed of entirely ones can ever be prime. Naturally, any number composed entirely of the digit D, will always be divisible by the single digit number D, and so only rep-unit numbers can be prime. Repunit numbers are a subset of the rep-digit family, so numbers composed only of a string of ones. 11 is the first such repunit prime. We can write them in MATLAB as a simple expression:

RU = @(N) (sym(10).^N - 1)/9;

RU(N) is a number composed only of the digit 1, with N decimal digits. This family also follows a recurrence relation, and so we could use a similar scheme as was used to find rough members of the set 3^N-4.

RU(N+1) == 10*RU(N) + 1

However, repunit numbers are rarely prime. Looking out as far as 500 digit repunit numbers, we would see primes are pretty scarce in this specific family.

find(isprime(RU(1:500)))

ans =

2 19 23 317

There are of course good reasons why repunit numbers are rarely prime. One of them is they can only ever be prime when the number of digits is also prime. This is easy to show, as you can always factor any repunit number with a composite number of digits in a simple way:

1111 (4 digits) = 11*101

111111111 (9 digits) = 111*1001001

Finally, I'll mention that Mersenne primes are indeed another example of repunit primes, when expressed in base 2. A fun fact: a Mersenne number of the form 2^n-1, when n is prime, can only have prime factors of the form 1+2*k*n. Even the Mersenne number itself will be of the same general form. And remember that a Mersenne number M(n) can only ever be prime when n is itself prime. Try it! For example, 11 is prime.

Mn = @(n) sym(2).^n - 1;

Mn(11)

ans =

2047

Note that 2047 = 1 + 186*11. But M(11) is not itself prime.

factor(Mn(11))

ans =

[23, 89]

Looking carefully at both of those factors, we see that 23 == 1+2*11, and 89 = 1+8*11.

How does this help us? Perhaps you may see where this is going. The largest known Mersenne prime at this date is Mn(136279841). This is one seriously massive prime, containing 41,024,320 decimal digits. I have no plans to directly test numbers of that size for primality here, at least not with my current computing capacity. Regardless, even at that realm of immensity, we can still do something.

If the largest known Mersenne prime comes from n=136279841, then the next such prime must have a larger prime exponent. What are the next few primes that exceed 136279841?

np = NaN(1,11); np(1) = 136279841;

for i = 1:10

np(i+1) = nextprime(np(i)+1);

end

np(1) = [];

np

np =

Columns 1 through 8

136279879 136279901 136279919 136279933 136279967 136279981 136279987 136280003

Columns 9 through 10

136280009 136280051

The next 10 candidates for Mersenne primality lie in the set Mn(np), though it is unlikely that any of those Mersenne numbers will be prime. But ... is it possible that any of them may form the next Mersenne prime? At the very least, we can exclude a few of them.

for i = 1:10

2*find(powermod(sym(2),np(i),1+2*(1:50000)*np(i))==1)

end

ans =

18 40 64

ans =

1×0 empty double row vector

ans =

2

ans =

1×0 empty double row vector

ans =

1×0 empty double row vector

ans =

1×0 empty double row vector

ans =

1×0 empty double row vector

ans =

1×0 empty double row vector

ans =

1×0 empty double row vector

ans =

2

Even with this quick test which took only a few seconds to run on my computer, we see that 3 of those Mersenne numbers are clearly not prime. In fact, we already know three of the factors of M(136279879), as 1+[18,40,64]*136279879.

You might ask, when is the MOD style test, using a large scale test for roughness against many thousands or millions of small primes, when is it better than the use of GCD? The answer here is clear. Use the large scale mod test when you can easily move from one member of the family to the next, typically using a linear recurrence. Simple such examples of this are:

1. Repunit numbers

General form: R(n) = (10^n-1)/9

Recurrence: R(n+1) = 10*R(n) + 1, R(0) = 1, R(1) = 11

2. Fibonacci numbers.

Recurrence: F(n+1) = F(n) + F(n-1), F(0) = 0, F(1) = 1

3. Mersenne numbers.

General form: M(n) = 2^n - 1

Recurrence: M(n+1) = 2*M(n) + 1

4. Cullen numbers, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cullen_number

General form: C(n) = n*2^n + 1

Recurrence: C(n+1) = 4*C(n) + 4*C(n-1) + 1

5. Hampshire numbers: (My own choice of name)

General form: H(n,b) = (n+1)*b^n - 1

Recurrence: H(n+1,b) = 2*b*H(n-1,b) - b^2*H(n-2,b) - (b-1)^2, H(0,b) = 0, H(1,b) = 2*b-1

6. Tin numbers, so named because Sn is the atomic symbol for tin.

General form: S(n) = 2*n*F(n) + 1, where F(n) is the nth Fibonacci number.

Recurrence: S(n) = S(n-5) + S(n-4) - 3*S(n-3) - S(n-2) +3*S(n-1);

To wrap thing up, I hope you have enjoyed this beginning of a journey into large primes and non-primes. I've shown a few ways we can use roughness, first in a constructive way to identify numbers which may harbor primes in a greater density than would otherwise be expected. Next, using GCD in a very pretty way, and finally by use of MOD and the full power of MATLAB to test elements of a sequence of numbers for potential primality.

My next post will delve into the world of Fermat and his little theorem, showing how it can be used as a stronger test for primality (though not perfect.)

Yes, some readers might now argue that I used roughness in a crazy way in my last post, in my approach to finding a large twin prime pair. That is, I deliberately constructed a family of integers that were known to be a-priori rough. But, suppose I gave you some large, rather arbitrarily constructed number, and asked you to tell me if it is prime? For example, to pull a number out of my hat, consider

P = sym(2)^122397 + 65;

floor(vpa(log10(P) + 1))

36846 decimal digits is pretty large. And in fact, large enough that sym/isprime in R2024b will literally choke on it. But is it prime? Can we efficiently learn if it is at least not prime?

A nice way to learn the roughness of even a very large number like this is to use GCD.

gcd(P,prod(sym(primes(10000))))

If the greatest common divisor between P and prod(sym(primes(10000))) is 1, then P is NOT divisible by any small prime from that set, since they have no common divisors. And so we can learn that P is indeed fairly rough, 10000-rough in fact. That means P is more likely to be prime than most other large integers in that domain.

gcd(P,prod(sym(primes(100000))))

However, this rather efficiently tells us that in fact, P is not prime, as it has a common factor with some integer greater than 1, and less then 1e5.

I suppose you might think this is nothing different from doing trial divides, or using the mod function. But GCD is a much faster way to solve the problem. As a test, I timed the two.

timeit(@() gcd(P,prod(sym(primes(100000)))))

timeit(@() any(mod(P,primes(100000)) == 0))

Even worse, in the first test, much if not most of that time is spent in merely computing the product of those primes.

pprod = prod(sym(primes(100000)));

timeit(@() gcd(P,pprod))

So even though pprod is itself a huge number, with over 43000 decimal digits, we can use it quite efficiently, especially if you precompute that product if you will do this often.

How might I use roughness, if my goal was to find the next larger prime beyond 2^122397? I'll look fairly deeply, looking only for 1e7-rough numbers, because these numbers are pretty seriously large. Any direct test for primality will take some serious time to perform.

pprod = prod(sym(primes(10000000)));

find(1 == gcd(sym(2)^122397 + (1:2:199),pprod))*2 - 1

2^122397 plus any one of those numbers is known to be 1e7-rough, and therefore very possibly prime. A direct test at this point would surely take hours and I don't want to wait that long. So I'll back off just a little to identify the next prime that follows 2^10000. Even that will take some CPU time.

What is the next prime that follows 2^10000? In this case, the number has a little over 3000 decimal digits. But, even with pprod set at the product of primes less than 1e7, only a few seconds were needed to identify many numbers that are 1e7-rough.

P10000 = sym(2)^10000;

k = find(1 == gcd(P10000 + (1:2:1999),pprod))*2 - 1

k =

Columns 1 through 8

15 51 63 85 165 171 177 183

Columns 9 through 16

253 267 273 295 315 421 427 451

Columns 17 through 24

511 531 567 601 603 675 687 717

Columns 25 through 32

723 735 763 771 783 793 795 823

Columns 33 through 40

837 853 865 885 925 955 997 1005

Columns 41 through 48

1017 1023 1045 1051 1071 1075 1095 1107

Columns 49 through 56

1261 1285 1287 1305 1371 1387 1417 1497

Columns 57 through 64

1507 1581 1591 1593 1681 1683 1705 1771

Columns 65 through 69

1773 1831 1837 1911 1917

Among the 1000 odd numbers immediately following 2^10000, there are exactly 69 that are 1e7-rough. Every other odd number in that sequence is now known to be composite, and even though we don't know the full factorization of those 931 composite numbers, we don't care in the context as they are not prime. I would next apply a stronger test for primality to only those few candidates which are known to be rough. Eventually after an extensive search, we would learn the next prime succeeding 2^10000 is 2^10000+13425.

In my next post, I show how to use MOD, and all the cores in your CPU to test for roughness.

How can we use roughness in an effective context to identify large primes? I can quickly think of quite a few examples where we might do so. Again, remember I will be looking for primes with not just hundreds of decimal digits, or even only a few thousand digits. The eventual target is higher than that. Forget about targets for now though, as this is a journey, and what matters in this journey is what we may learn along the way.

I think the most obvious way to employ roughness is in a search for twin primes. Though not yet proven, the twin prime conjecture:

If it is true, it tells us there are infinitely many twin prime pairs. A twin prime pair is two integers with a separation of 2, such that both of them are prime. We can find quite a few of them at first, as we have {3,5}, {5,7}, {11,13}, etc. But there is only ONE pair of integers with a spacing of 1, such that both of them are prime. That is the pair {2,3}. And since primes are less and less common as we go further out, possibly there are only a finite number of twins with a spacing of exactly 2? Anyway, while I'm fairly sure the twin prime conjecture will one day be shown to be true, it can still be interesting to search for larger and larger twin prime pairs. The largest such known pair at the moment is

2996863034895*2^1290000 +/- 1

This is a pair with 388342 decimal digits. And while seriously large, it is still in range of large integers we can work with in MATLAB, though certainly not in double precision. In my own personal work on my own computer, I've done prime testing on integers (in MATLAB) with considerably more than 100,000 decimal digits.

But, again you may ask, just how does roughness help us here? In fact, this application of roughness is not new with me. You might want to read about tools like NewPGen {https://t5k.org/programs/NewPGen/} which sieves out numbers known to be composite, before any direct tests for primality are performed.

Before we even try to talk about numbers with thousands or hundreds of thousands of decimal digits, look at 6=2*3. You might observe

isprime([-1,1] + 6)

shows that both 5 and 7 are prime. This should not be a surprise, but think about what happens, about why it generated a twin prime pair. 6 is divisible by both 2 and 3, so neither 5 or 7 can possibly be divisible by either small prime as they are one more or one less than a multiple of both 2 and 3. We can try this again, pushing the limits just a bit.

isprime([-1,1] + 2*3*5)

That is again interesting. 30=2*3*5 is evenly divisible by 2, 3, and 5. The result is both 29 and 31 are prime, because adding 1 or subtracting 1 from a multiple of 2, 3, or 5 will always result in a number that is not divisible by any of those small primes. The next larger prime after 5 is 7, but it cannot be a factor of 29 or 31, since it is greater than both sqrt(29) and sqrt(31).

We have quite efficiently found another twin prime pair. Can we take this a step further? 210=2*3*5*7 is the smallest such highly composite number that is divisible by all primes up to 7. Can we use the same trick once more?

isprime([-1,1] + 2*3*5*7)

And here the trick fails, because 209=11*19 is not in fact prime. However, can we use the large twin prime trick we saw before? Consider numbers of the form [-1,1]+a*210, where a is itself some small integer?

a = 2;

isprime([-1,1] + a*2*3*5*7)

I did not need to look far, only out to a=2, because both 419 and 421 are prime. You might argue we have formed a twin prime "factory", of sorts. Next, I'll go out as far as the product of all primes not exceeding 60. This is a number with 22 decimal digits, already too large to represent as a double, or even as uint64.

prod(sym(primes(60)))

a = find(all(isprime([-1;1] + prod(sym(primes(60)))*(1:100)),1))

That easily identifies 3 such twin prime pairs, each of which has roughly 23 decimal digits, each of which have the form a*1922760350154212639070+/-1. The twin prime factory is still working well. Going further out to integers with 37 decimal digits, we can easily find two more such pairs that employ the product of all primes not exceeding 100.

prod(sym(primes(100)))

a = find(all(isprime([-1;1] + prod(sym(primes(100)))*(1:100)),1))

This is in fact an efficient way of identifying large twin prime pairs, because it chooses a massively composite number as the product of many distinct small primes. Adding or subtracting 1 from such a number will result always in a rough number, not divisible by any of the primes employed. With a little more CPU time expended, now working with numbers with over 1000 decimal digits, I will claim this next pair forms a twin prime pair, and is the smallest such pair we can generate in this way from the product of the primes not exceeding 2500.

isprime(7826*prod(sym(primes(2500))) + [-1 1])

ans =

logical

1

Unfortunately, 1000 decimal digits is at or near the limit of what the sym/isprime tool can do for us. It does beg the question, asking if there are alternatives to the sym/isprime tool, as an isProbablePrime test, usually based on Miller-Rabin is often employed. But this is gist for yet another set of posts.

Anyway, I've done a search for primes of the form

a*prod(sym(primes(10000))) +/- 1

having gone out as far as a = 600000, with no success as of yet. (My estimate is I will find a pair by the time I get near 5e6 for a.) Anyway, if others can find a better way to search for large twin primes in MATLAB, or if you know of a larger twin prime pair of this extended form, feel free to chime in.

My next post shows how to use GCD in a very nice way to identify roughness, on a large scale.

What is a rough number? What can they be used for? Today I'll take you down a journey into the land of prime numbers (in MATLAB). But remember that a journey is not always about your destination, but about what you learn along the way. And so, while this will be all about primes, and specifically large primes, before we get there we need some background. That will start with rough numbers.

Rough numbers are what I would describe as wannabe primes. Almost primes, and even sometimes prime, but often not prime. They could've been prime, but may not quite make it to the top. (If you are thinking of Marlon Brando here, telling us he "could've been a contender", you are on the right track.)

Mathematically, we could call a number k-rough if it is evenly divisible by no prime smaller than k. (Some authors will use the term k-rough to denote a number where the smallest prime factor is GREATER than k. The difference here is a minor one, and inconsequential for my purposes.) And there are also smooth numbers, numerical antagonists to the rough ones, those numbers with only small prime factors. They are not relevant to the topic today, even though smooth numbers are terribly valuable tools in mathematics. Please forward my apologies to the smooth numbers.

Have you seen rough numbers in use before? Probably so, at least if you ever learned about the sieve of Eratosthenes for prime numbers, though probably the concept of roughness was never explicitly discussed at the time. The sieve is simple. Suppose you wanted a list of all primes less than 100? (Without using the primes function itself.)

% simple sieve of Eratosthenes

Nmax = 100;

N = true(1,Nmax); % A boolean vector which when done, will indicate primes

N(1) = false; % 1 is not a prime by definition

nextP = find(N,1,'first'); % the first prime is 2

while nextP <= sqrt(Nmax)

% flag multiples of nextP as not prime

N(nextP*nextP:nextP:end) = false;

% find the first element after nextP that remains true

nextP = nextP + find(N(nextP+1:end),1,'first');

end

primeList = find(N)

Indeed, that is the set of all 25 primes not exceeding 100. If you think about how the sieve worked, it first found 2 is prime. Then it discarded all integer multiples of 2. The first element after 2 that remains as true is 3. 3 is of course the second prime. At each pass through the loop, the true elements that remain correspond to numbers which are becoming more and more rough. By the time we have eliminated all multiples of 2, 3, 5, and finally 7, everything else that remains below 100 must be prime! The next prime on the list we would find is 11, but we have already removed all multiples of 11 that do not exceed 100, since 11^2=121. For example, 77 is 11*7, but we already removed it, because 77 is a multiple of 7.

Such a simple sieve to find primes is great for small primes. However is not remotely useful in terms of finding primes with many thousands or even millions of decimal digits. And that is where I want to go, eventually. So how might we use roughness in a useful way? You can think of roughness as a way to increase the relative density of primes. That is, all primes are rough numbers. In fact, they are maximally rough. But not all rough numbers are primes. We might think of roughness as a necessary, but not sufficient condition to be prime.

How many primes lie in the interval [1e6,2e6]?

numel(primes(2e6)) - numel(primes(1e6))

There are 70435 primes greater than 1e6, but less than 2e6. Given there are 1 million natural numbers in that set, roughly 7% of those numbers were prime. Next, how many 100-rough numbers lie in that same interval?

N = (1e6:2e6)';

roughInd = all(mod(N,primes(100)) > 0,2);

sum(roughInd)

That is, there are 120571 100-rough numbers in that interval, but all those 70435 primes form a subset of the 100-rough numbers. What does this tell us? Of the 1 million numbers in that interval, approximately 12% of them were 100-rough, but 58% of the rough set were prime.

The point being, if we can efficiently identify a number as being rough, then we can substantially increase the chance it is also prime. Roughness in this sense is a prime densifier. (Is that even a word? It is now.) If we can reduce the number of times we need to perform an explicit isprime test, that will gain greatly because a direct test for primality is often quite costly in CPU time, at least on really large numbers.

In my next post, I'll show some ways we can employ rough numbers to look for some large primes.

I've been trying this problem a lot of time and i don't understand why my solution doesnt't work.

In 4 tests i get the error Assertion failed but when i run the code myself i get the diag and antidiag correctly.

function [diag_elements, antidg_elements] = your_fcn_name(x)

[m, n] = size(x);

% Inicializar los vectores de la diagonal y la anti-diagonal

diag_elements = zeros(1, min(m, n));

antidg_elements = zeros(1, min(m, n));

% Extraer los elementos de la diagonal

for i = 1:min(m, n)

diag_elements(i) = x(i, i);

end

% Extraer los elementos de la anti-diagonal

for i = 1:min(m, n)

antidg_elements(i) = x(m-i+1, i);

end

end

I love it all

47%

Love the first snowfall only

13%

Hate it

18%

It doesn't snow where I live

21%

38 voti

My following code works running Matlab 2024b for all test cases. However, 3 of 7 tests fail (#1, #4, & #5) the QWERTY Shift Encoder problem. Any ideas what I am missing?

Thanks in advance.

keyboardMap1 = {'qwertyuiop[;'; 'asdfghjkl;'; 'zxcvbnm,'};

keyboardMap2 = {'QWERTYUIOP{'; 'ASDFGHJKL:'; 'ZXCVBNM<'};

if length(s) == 0

se = s;

end

for i = 1:length(s)

if double(s(i)) >= 65 && s(i) <= 90

row = 1;

col = 1;

while ~strcmp(s(i), keyboardMap2{row}(col))

if col < length(keyboardMap2{row})

col = col + 1;

else

row = row + 1;

col = 1;

end

end

se(i) = keyboardMap2{row}(col + 1);

elseif double(s(i)) >= 97 && s(i) <= 122

row = 1;

col = 1;

while ~strcmp(s(i), keyboardMap1{row}(col))

if col < length(keyboardMap1{row})

col = col + 1;

else

row = row + 1;

col = 1;

end

end

se(i) = keyboardMap1{row}(col + 1);

else

se(i) = s(i);

end

% if ~(s(i) = 65 && s(i) <= 90) && ~(s(i) >= 97 && s(i) <= 122)

% se(i) = s(i);

% end

end

If you have a folder with an enormous number of files and want to use the uigetfile function to select specific files, you may have noticed a significant delay in displaying the file list.

Thanks to the assistance from MathWorks support, an interesting behavior was observed.

For example, if a folder such as Z:\Folder1\Folder2\data contains approximately 2 million files, and you attempt to use uigetfile to access files with a specific extension (e.g., *.ext), the following behavior occurs:

Method 1: This takes minutes to show me the list of all files

[FileName, PathName] = uigetfile('Z:\Folder1\Folder2\data\*.ext', 'File selection');

Method 2: This takes less than a second to display all files.

[FileName, PathName] = uigetfile('*.ext', 'File selection','Z:\Folder1\Folder2\data');

Method 3: This method also takes minutes to display the file list. What is intertesting is that this method is the same as Method 2, except that a file seperator "\" is added at the end of the folder string.

[FileName, PathName] = uigetfile('*.ext', 'File selection','Z:\Folder1\Folder2\data\');

I was informed that the Mathworks development team has been informed of this strange behaviour.

I am using 2023a, but think this should be the same for newer versions.

This post is more of a "tips and tricks" guide than a question.

If you have a folder with an enormous number of files and want to use the uigetfile function to select specific files, you may have noticed a significant delay in displaying the file list.

Thanks to the assistance from MathWorks support, an interesting behavior was observed.

For example, if a folder such as Z:\Folder1\Folder2\data contains approximately 2 million files, and you attempt to use uigetfile to access files with a specific extension (e.g., *.ext), the following behavior occurs:

Method 1: This takes minutes to show me the list of all files

[FileName, PathName] = uigetfile('Z:\Folder1\Folder2\data\*.ext', 'File selection');

Method 2: This takes less than a second to display all files.

[FileName, PathName] = uigetfile('*.ext', 'File selection','Z:\Folder1\Folder2\data');

Method 3: This method also takes minutes to display the file list. What is intertesting is that this method is the same as Method 2, except that a file seperator "\" is added at the end of the folder string.

[FileName, PathName] = uigetfile('*.ext', 'File selection','Z:\Folder1\Folder2\data\');

I was informed that the Mathworks development team has been informed of this strange behaviour.

I am using 2023a, but think this should be the same for newer versions.

Christmas is coming, here are two dynamic Christmas tree drawing codes:

Crystal XMas Tree

function XmasTree2024_1

fig = figure('Units','normalized', 'Position',[.1,.1,.5,.8],...

'Color',[0,9,33]/255, 'UserData',40 + [60,65,75,72,0,59,64,57,74,0,63,59,57,0,1,6,45,75,61,74,28,57,76,57,1,1]);

axes('Parent',fig, 'Position',[0,-1/6,1,1+1/3], 'UserData',97 + [18,11,0,13,3,0,17,4,17],...

'XLim',[-1.5,1.5], 'YLim',[-1.5,1.5], 'ZLim',[-.2,3.8], 'DataAspectRatio', [1,1,1], 'NextPlot','add',...

'Projection','perspective', 'Color',[0,9,33]/255, 'XColor','none', 'YColor','none', 'ZColor','none')

%% Draw Christmas tree

F = [1,3,4;1,4,5;1,5,6;1,6,3;...

2,3,4;2,4,5;2,5,6;2,6,3];

dP = @(V) patch('Faces',F, 'Vertices',V, 'FaceColor',[0 71 177]./255,...

'FaceAlpha',rand(1).*0.2+0.1, 'EdgeColor',[0 71 177]./255.*0.8,...

'EdgeAlpha',0.6, 'LineWidth',0.5, 'EdgeLighting','gouraud', 'SpecularStrength',0.3);

r = .1; h = .8;

V0 = [0,0,0; 0,0,1; 0,r,h; r,0,h; 0,-r,h; -r,0,h];

% Rotation matrix

Rx = @(V, theta) V*[1 0 0; 0 cos(theta) sin(theta); 0 -sin(theta) cos(theta)];

Rz = @(V, theta) V*[cos(theta) sin(theta) 0;-sin(theta) cos(theta) 0; 0 0 1];

N = 180; Vn = zeros(N, 3); eval(char(fig.UserData))

for i = 1:N

tV = Rz(Rx(V0.*(1.2 - .8.*i./N + rand(1).*.1./i^(1/5)), pi/3.*(1 - .6.*i./N)), i.*pi/8.1 + .001.*i.^2) + [0,0,.016.*i];

dP(tV); Vn(i,:) = tV(2,:);

end

scatter3(Vn(:,1).*1.02,Vn(:,2).*1.02,Vn(:,3).*1.01, 30, 'w', 'Marker','*', 'MarkerEdgeAlpha',.5)

%% Draw Star of Bethlehem

w = .3; R = .62; r = .4; T = (1/8:1/8:(2 - 1/8)).'.*pi;

V8 = [ 0, 0, w; 0, 0,-w;

1, 0, 0; 0, 1, 0; -1, 0, 0; 0,-1,0;

R, R, 0; -R, R, 0; -R,-R, 0; R,-R,0;

cos(T).*r, sin(T).*r, T.*0];

F8 = [1,3,25; 1,3,11; 2,3,25; 2,3,11; 1,7,11; 1,7,13; 2,7,11; 2,7,13;

1,4,13; 1,4,15; 2,4,13; 2,4,15; 1,8,15; 1,8,17; 2,8,15; 2,8,17;

1,5,17; 1,5,19; 2,5,17; 2,5,19; 1,9,19; 1,9,21; 2,9,19; 2,9,21;

1,6,21; 1,6,23; 2,6,21; 2,6,23; 1,10,23; 1,10,25; 2,10,23; 2,10,25];

V8 = Rx(V8.*.3, pi/2) + [0,0,3.5];

patch('Faces',F8, 'Vertices',V8, 'FaceColor',[255,223,153]./255,...

'EdgeColor',[255,223,153]./255, 'FaceAlpha', .2)

%% Draw snow

sXYZ = rand(200,3).*[4,4,5] - [2,2,0];

sHdl1 = plot3(sXYZ(1:90,1),sXYZ(1:90,2),sXYZ(1:90,3), '*', 'Color',[.8,.8,.8]);

sHdl2 = plot3(sXYZ(91:200,1),sXYZ(91:200,2),sXYZ(91:200,3), '.', 'Color',[.6,.6,.6]);

annotation(fig,'textbox',[0,.05,1,.09], 'Color',[1 1 1], 'String','Merry Christmas Matlaber',...

'HorizontalAlignment','center', 'FontWeight','bold', 'FontSize',48,...

'FontName','Times New Roman', 'FontAngle','italic', 'FitBoxToText','off','EdgeColor','none');

% Rotate the Christmas tree and let the snow fall

for i=1:1e8

sXYZ(:,3) = sXYZ(:,3) - [.05.*ones(90,1); .06.*ones(110,1)];

sXYZ(sXYZ(:,3)<0, 3) = sXYZ(sXYZ(:,3) < 0, 3) + 5;

sHdl1.ZData = sXYZ(1:90,3); sHdl2.ZData = sXYZ(91:200,3);

view([i,30]); drawnow; pause(.05)

end

end

Curved XMas Tree

function XmasTree2024_2

fig = figure('Units','normalized', 'Position',[.1,.1,.5,.8],...

'Color',[0,9,33]/255, 'UserData',40 + [60,65,75,72,0,59,64,57,74,0,63,59,57,0,1,6,45,75,61,74,28,57,76,57,1,1]);

axes('Parent',fig, 'Position',[0,-1/6,1,1+1/3], 'UserData',97 + [18,11,0,13,3,0,17,4,17],...

'XLim',[-6,6], 'YLim',[-6,6], 'ZLim',[-16, 1], 'DataAspectRatio', [1,1,1], 'NextPlot','add',...

'Projection','perspective', 'Color',[0,9,33]/255, 'XColor','none', 'YColor','none', 'ZColor','none')

%% Draw Christmas tree

[X,T] = meshgrid(.4:.1:1, 0:pi/50:2*pi);

XM = 1 + sin(8.*T).*.05;

X = X.*XM; R = X.^(3).*(.5 + sin(8.*T).*.02);

dF = @(R, T, X) surf(R.*cos(T), R.*sin(T), -X, 'EdgeColor',[20,107,58]./255,...

'FaceColor', [20,107,58]./255, 'FaceAlpha',.2, 'LineWidth',1);

CList = [254,103,110; 255,191,115; 57,120,164]./255;

for i = 1:5

tR = R.*(2 + i); tT = T+i; tX = X.*(2 + i) + i;

SFHdl = dF(tR, tT, tX);

[~, ind] = sort(SFHdl.ZData(:)); ind = ind(1:8);

C = CList(randi([1,size(CList,1)], [8,1]), :);

scatter3(tR(ind).*cos(tT(ind)), tR(ind).*sin(tT(ind)), -tX(ind), 120, 'filled',...

'CData', C, 'MarkerEdgeColor','none', 'MarkerFaceAlpha',.3)

scatter3(tR(ind).*cos(tT(ind)), tR(ind).*sin(tT(ind)), -tX(ind), 60, 'filled', 'CData', C)

end

%% Draw Star of Bethlehem

Rx = @(V, theta) V*[1 0 0; 0 cos(theta) sin(theta); 0 -sin(theta) cos(theta)];

% Rz = @(V, theta) V*[cos(theta) sin(theta) 0;-sin(theta) cos(theta) 0; 0 0 1];

w = .3; R = .62; r = .4; T = (1/8:1/8:(2 - 1/8)).'.*pi;

V8 = [ 0, 0, w; 0, 0,-w;

1, 0, 0; 0, 1, 0; -1, 0, 0; 0,-1,0;

R, R, 0; -R, R, 0; -R,-R, 0; R,-R,0;

cos(T).*r, sin(T).*r, T.*0];

F8 = [1,3,25; 1,3,11; 2,3,25; 2,3,11; 1,7,11; 1,7,13; 2,7,11; 2,7,13;

1,4,13; 1,4,15; 2,4,13; 2,4,15; 1,8,15; 1,8,17; 2,8,15; 2,8,17;

1,5,17; 1,5,19; 2,5,17; 2,5,19; 1,9,19; 1,9,21; 2,9,19; 2,9,21;

1,6,21; 1,6,23; 2,6,21; 2,6,23; 1,10,23; 1,10,25; 2,10,23; 2,10,25];

V8 = Rx(V8.*.8, pi/2) + [0,0,-1.3];

patch('Faces',F8, 'Vertices',V8, 'FaceColor',[255,223,153]./255,...

'EdgeColor',[255,223,153]./255, 'FaceAlpha', .2)

annotation(fig,'textbox',[0,.05,1,.09], 'Color',[1 1 1], 'String','Merry Christmas Matlaber',...

'HorizontalAlignment','center', 'FontWeight','bold', 'FontSize',48,...

'FontName','Times New Roman', 'FontAngle','italic', 'FitBoxToText','off','EdgeColor','none');

%% Draw snow

sXYZ = rand(200,3).*[12,12,17] - [6,6,16];

sHdl1 = plot3(sXYZ(1:90,1),sXYZ(1:90,2),sXYZ(1:90,3), '*', 'Color',[.8,.8,.8]);

sHdl2 = plot3(sXYZ(91:200,1),sXYZ(91:200,2),sXYZ(91:200,3), '.', 'Color',[.6,.6,.6]);

for i=1:1e8

sXYZ(:,3) = sXYZ(:,3) - [.1.*ones(90,1); .12.*ones(110,1)];

sXYZ(sXYZ(:,3)<-16, 3) = sXYZ(sXYZ(:,3) < -16, 3) + 17.5;

sHdl1.ZData = sXYZ(1:90,3); sHdl2.ZData = sXYZ(91:200,3);

view([i,30]); drawnow; pause(.05)

end

end

I wish all MATLABers a Merry Christmas in advance!

Watt's Up with Electric Vehicles?EV modeling Ecosystem (Eco-friendly Vehicles), V2V Communication and V2I communications thereby emitting zero Emissions to considerably reduce NOx ,Particulates matters,CO2 given that Combustion is always incomplete and will always be.

Reduction of gas emissions outside to the environment will improve human life span ,few epidemic diseases and will result in long life standard

Hi! My name is Mike McLernon, and I’m a product marketing engineer with MathWorks. In my role, I look at the trends ongoing in the wireless industry, across lots of different standards (think 5G, WLAN, SatCom, Bluetooth, etc.), and I seek to shape and guide the software that MathWorks builds to respond to these trends. That’s all about communicating within the Mathworks organization, but every so often it’s worth communicating these trends to our audience in the world at large. Many of the people reading this are engineers (or engineers at heart), and we all want to know what’s happening in the geek world around us. I think that now is one of these times to communicate an important milestone. So, without further ado . . .

Bluetooth 6.0 is here! Announced in September by the Bluetooth Special Interest Group (SIG), it’s making more advances in its quest to create a “world without wires”. A few of the salient features in Bluetooth 6.0 are:

- Channel sounding (for accurate distance measurements)

- Decision-based advertising filtering (for more efficient channel scanning)

- Monitoring advertisers (for improved energy efficiency when devices come into and go out of range)

- Frame space updates (for both higher throughput and better coexistence management)

Bluetooth 6.0 includes other features as well, but the SIG has put special promotional emphasis on channel sounding (CS), which once upon a time was called High Accuracy Distance Measurement (HADM). The SIG has said that CS is a step towards true distance awareness, and 10 cm ranging accuracy. I think their emphasis is in exactly the right place, so let’s learn more about this technology and how it is used.

CS can be used for the following use cases:

- Keyless vehicle entry, performed by communication between a key fob or phone and the car’s anchor points

- Smart locks, to permit access only when an authorized device is within a designated proximity to the locks

- Geofencing, to limit access to designated areas

- Warehouse management, to monitor inventory and manage logistics

- Asset tracking for virtually any object of interest

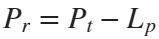

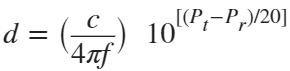

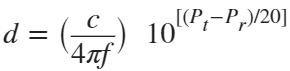

In the past, Bluetooth devices would use a received signal strength indicator (RSSI) measurement to infer the distance between two of them. They would assume a free space path loss on the link, and use a straightforward equation to estimate distance:

where

whereSo in this method,  . But if the signal suffers more loss from multipath or shadowing, then the distance would be overestimated. Something better needed to be found.

. But if the signal suffers more loss from multipath or shadowing, then the distance would be overestimated. Something better needed to be found.

. But if the signal suffers more loss from multipath or shadowing, then the distance would be overestimated. Something better needed to be found.

. But if the signal suffers more loss from multipath or shadowing, then the distance would be overestimated. Something better needed to be found.Bluetooth 6.0 introduces not one, but two ways to accurately measure distance:

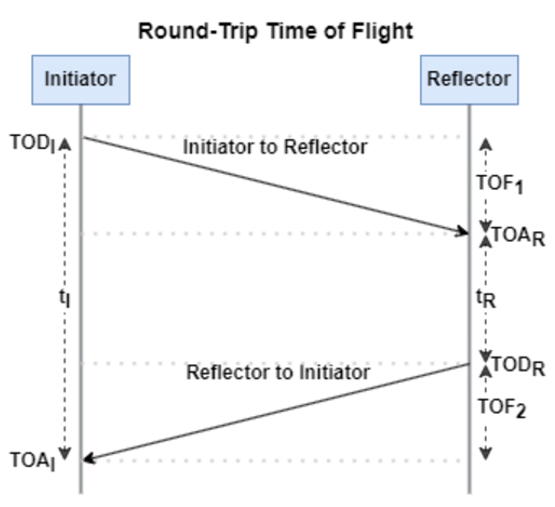

- Round-trip time (RTT) measurement

- Phase-based ranging (PBR) measurement

The RTT measurement method uses the fact that the Bluetooth signal time of flight (TOF) between two devices is half the RTT. It can then accurately compute the distance d as

, where c is again the speed of light. This method requires accurate measurements of the time of departure (TOD) of the outbound signal from device 1 (the Initiator), time of arrival (TOA) of the outbound signal to device 2 (the Reflector), TOD of the return signal from device 2, and TOA of the return signal to device 1. The diagram below shows the signal paths and the times.

, where c is again the speed of light. This method requires accurate measurements of the time of departure (TOD) of the outbound signal from device 1 (the Initiator), time of arrival (TOA) of the outbound signal to device 2 (the Reflector), TOD of the return signal from device 2, and TOA of the return signal to device 1. The diagram below shows the signal paths and the times.

If you want to see how you can use MATLAB to simulate the RTT method, take a look at Estimate Distance Between Bluetooth LE Devices by Using Channel Sounding and Round-Trip Timing.

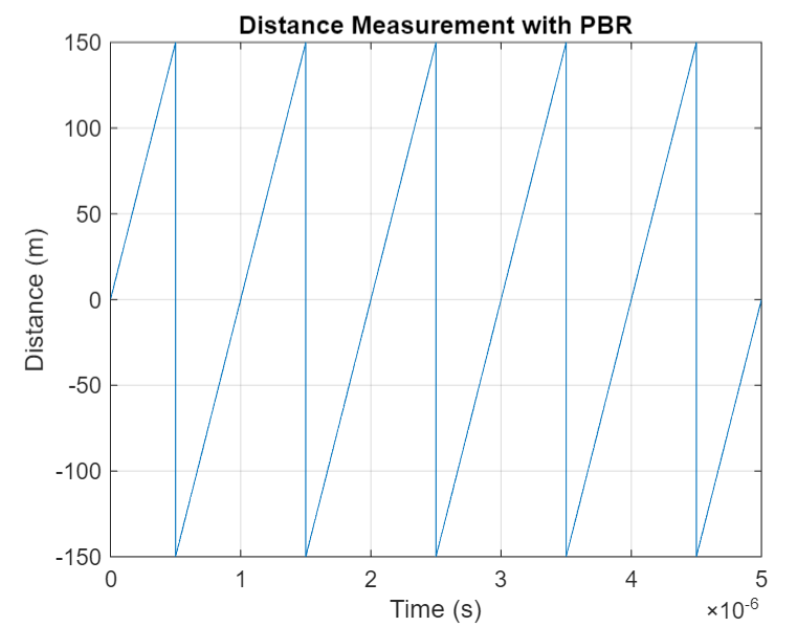

The PBR method uses two Bluetooth signals of different frequencies to measure distance. These signals are simply tones – sine waves. Without going through the derivation, PBR calculates distance d as

The mod() operation is needed to eliminate ambiguities in the distance calculation and the final division by two is to convert a round trip distance to a one-way distance. Because a given phase difference value can hold true for an infinite number of distance values, the mod() operation chooses the smallest distance that satisfies the equation. Also, these tones can be as close as 1 MHz apart. In that case, the maximum resolvable distance measurement is about 150 m. The plot below shows that ambiguity and repetition in distance measurement.

If you want to see how you can use MATLAB to simulate the PBR method, take a look at Estimate Distance Between Bluetooth LE Devices by Using Channel Sounding and Phase-Based Ranging.

Bluetooth 6.0 outlines RTT and PBR distance measurement methods, but CS does not mandate a specific algorithm for calculating distance estimates. This flexibility allows device manufacturers to tailor solutions to various use cases, balancing computational complexity with required accuracy and adapting to different radio environments. Examples include simple phase difference calculations and FFT-based methods.

Although Bluetooth 6.0 is now out, it is far from a finished version. The SIG is actively working through the ratification process for two major extensions:

- High Data Throughput, up to 8 Mbps

- 5 and 6 GHz operation

See the last few minutes of this video from the SIG to learn more about these exciting future developments. And if you want to see more Bluetooth blogs, give a review of this one! Finally, if you have specific Bluetooth questions, give me a shout and let’s start a discussion!

So I made this.

clear

close all

clc

% inspired from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3CuUmy7jX6k

%% user parameters

h = 768;

w = 1024;

N_snowflakes = 50;

%% set figure window

figure(NumberTitle="off", ...

name='Mat-snowfalling-lab (right click to stop)', ...

MenuBar="none")

ax = gca;

ax.XAxisLocation = 'origin';

ax.YAxisLocation = 'origin';

axis equal

axis([0, w, 0, h])

ax.Color = 'k';

ax.XAxis.Visible = 'off';

ax.YAxis.Visible = 'off';

ax.Position = [0, 0, 1, 1];

%% first snowflake

ht = gobjects(1, 1);

for i=1:length(ht)

ht(i) = hgtransform();

ht(i).UserData = snowflake_factory(h, w);

ht(i).Matrix(2, 4) = ht(i).UserData.y;

ht(i).Matrix(1, 4) = ht(i).UserData.x;

im = imagesc(ht(i), ht(i).UserData.img);

im.AlphaData = ht(i).UserData.alpha;

colormap gray

end

%% falling snowflake

tic;

while true

% add a snowflake every 0.3 seconds

if toc > 0.3

if length(ht) < N_snowflakes

ht = [ht; hgtransform()];

ht(end).UserData = snowflake_factory(h, w);

ht(end).Matrix(2, 4) = ht(end).UserData.y;

ht(end).Matrix(1, 4) = ht(end).UserData.x;

im = imagesc(ht(end), ht(end).UserData.img);

im.AlphaData = ht(end).UserData.alpha;

colormap gray

end

tic;

end

ax.CLim = [0, 0.0005]; % prevent from auto clim

% move snowflakes

for i = 1:length(ht)

ht(i).Matrix(2, 4) = ht(i).Matrix(2, 4) + ht(i).UserData.velocity;

end

if strcmp(get(gcf, 'SelectionType'), 'alt')

set(gcf, 'SelectionType', 'normal')

break

end

drawnow

% delete the snowflakes outside the window

for i = length(ht):-1:1

if ht(i).Matrix(2, 4) < -length(ht(i).Children.CData)

delete(ht(i))

ht(i) = [];

end

end

end

%% snowflake factory

function snowflake = snowflake_factory(h, w)

radius = round(rand*h/3 + 10);

sigma = radius/6;

snowflake.velocity = -rand*0.5 - 0.1;

snowflake.x = rand*w;

snowflake.y = h - radius/3;

snowflake.img = fspecial('gaussian', [radius, radius], sigma);

snowflake.alpha = snowflake.img/max(max(snowflake.img));

end

Hi everyone, I wrote several fancy functions that may help your coding experience, since they are in very early developing stage, I will be thankful if anyone could try them and give some feedbacks. Currently I have following:

- fstr: a Python f-string like expression

- printf: an easy to use fprintf function, accepts multiple arguments with seperator, end string control.

I will bring more functions or packages like logger when I am available.

The code is open sourced at GitHub with simple examples: https://github.com/bentrainer/MMGA

MATLAB Comprehensive commands list:

- clc - clears command window, workspace not affected

- clear - clears all variables from workspace, all variable values are lost

- diary - records into a file almost everything that appears in command window.

- exit - exits the MATLAB session

- who - prints all variables in the workspace

- whos - prints all variables in current workspace, with additional information.

Ch. 2 - Basics:

- Mathematical constants: pi, i, j, Inf, Nan, realmin, realmax

- Precedence rules: (), ^, negation, */, +-, left-to-right

- and, or, not, xor

- exp - exponential

- log - natural logarithm

- log10 - common logarithm (base 10)

- sqrt (square root)

- fprintf("final amount is %f units.", amt);

- can have: %f, %d, %i, %c, %s

- %f - fixed-point notation

- %e - scientific notation with lowercase e

- disp - outputs to a command window

- % - fieldWith.precision convChar

- MyArray = [startValue : IncrementingValue : terminatingValue]

Linspace

linspace(xStart, xStop, numPoints)

% xStart: Starting value

% xStop: Stop value

% numPoints: Number of linear-spaced points, including xStart and xStop

% Outputs a row array with the resulting values

Logspace

logspace(powerStart, powerStop, numPoints)

% powerStart: Starting value 10^powerStart

% powerStop: Stop value 10^powerStop

% numPoints: Number of logarithmic spaced points, including 10^powerStart and 10^powerStop

% Outputs a row array with the resulting values

- Transpose an array with []'

Element-Wise Operations

rowVecA = [1, 4, 5, 2];

rowVecB = [1, 3, 0, 4];

sumEx = rowVecA + rowVecB % Element-wise addition

diffEx = rowVecA - rowVecB % Element-wise subtraction

dotMul = rowVecA .* rowVecB % Element-wise multiplication

dotDiv = rowVecA ./ rowVecB % Element-wise division

dotPow = rowVecA .^ rowVecB % Element-wise exponentiation

- isinf(A) - check if the array elements are infinity

- isnan(A)

Rounding Functions

- ceil(x) - rounds each element of x to nearest integer >= to element

- floor(x) - rounds each element of x to nearest integer <= to element

- fix(x) - rounds each element of x to nearest integer towards 0

- round(x) - rounds each element of x to nearest integer. if round(x, N), rounds N digits to the right of the decimal point.

- rem(dividend, divisor) - produces a result that is either 0 or has the same sign as the dividen.

- mod(dividend, divisor) - produces a result that is either 0 or same result as divisor.

- Ex: 12/2, 12 is dividend, 2 is divisor

- sum(inputArray) - sums all entires in array

Complex Number Functions

- abs(z) - absolute value, is magnitude of complex number (phasor form r*exp(j0)

- angle(z) - phase angle, corresponds to 0 in r*exp(j0)

- complex(a,b) - creates complex number z = a + jb

- conj(z) - given complex conjugate a - jb

- real(z) - extracts real part from z

- imag(z) - extracts imaginary part from z

- unwrap(z) - removes the modulus 2pi from an array of phase angles.

Statistics Functions

- mean(xAr) - arithmetic mean calculated.

- std(xAr) - calculated standard deviation

- median(xAr) - calculated the median of a list of numbers

- mode(xAr) - calculates the mode, value that appears most often

- max(xAr)

- min(xAr)

- If using &&, this means that if first false, don't bother evaluating second

Random Number Functions

- rand(numRand, 1) - creates column array

- rand(1, numRand) - creates row array, both with numRand elements, between 0 and 1

- randi(maxRandVal, numRan, 1) - creates a column array, with numRand elements, between 1 and maxRandValue.

- randn(numRand, 1) - creates a column array with normally distributed values.

- Ex: 10 * rand(1, 3) + 6

- "10*rand(1, 3)" produces a row array with 3 random numbers between 0 and 10. Adding 6 to each element results in random values between 6 and 16.

- randi(20, 1, 5)

- Generates 5 (last argument) random integers between 1 (second argument) and 20 (first argument). The arguments 1 and 5 specify a 1 × 5 row array is returned.

Discrete Integer Mathematics

- primes(maxVal) - returns prime numbers less than or equal to maxVal

- isprime(inputNums) - returns a logical array, indicating whether each element is a prime number

- factor(intVal) - returns the prime factors of a number

- gcd(aVals, bVals) - largest integer that divides both a and b without a remainder

- lcm(aVals, bVals) - smallest positive integer that is divisible by both a and b

- factorial(intVals) - returns the factorial

- perms(intVals) - returns all the permutations of the elements int he array intVals in a 2D array pMat.

- randperm(maxVal)

- nchoosek(n, k)

- binopdf(x, n, p)

Concatenation

- cat, vertcat, horzcat

- Flattening an array, becomes vertical: sampleList = sampleArray ( : )

Dimensional Properties of Arrays

- nLargest = length(inArray) - number of elements along largest dimension

- nDim = ndims(inArray)

- nArrElement = numel(inArray) - nuber of array elements

- [nRow, nCol] = size(inArray) - returns the number of rows and columns on array. use (inArray, 1) if only row, (inArray, 2) if only column needed

- aZero = zeros(m, n) - creates an m by n array with all elements 0

- aOnes = ones(m, n) - creates an m by n array with all elements set to 1

- aEye = eye(m, n) - creates an m by n array with main diagonal ones

- aDiag = diag(vector) - returns square array, with diagonal the same, 0s elsewhere.

- outFlipLR = fliplr(A) - Flips array left to right.

- outFlipUD = flipud(A) - Flips array upside down.

- outRot90 = rot90(A) - Rotates array by 90 degrees counter clockwise around element at index (1,1).

- outTril = tril(A) - Returns the lower triangular part of an array.

- outTriU = triu(A) - Returns the upper triangular part of an array.

- arrayOut = repmat(subarrayIn, mRow, nCol), creates a large array by replicating a smaller array, with mRow x nCol tiling of copies of subarrayIn

- reshapeOut - reshape(arrayIn, numRow, numCol) - returns array with modifid dimensions. Product must equal to arrayIn of numRow and numCol.

- outLin = find(inputAr) - locates all nonzero elements of inputAr and returns linear indices of these elements in outLin.

- [sortOut, sortIndices] = sort(inArray) - sorts elements in ascending order, results result in sortOut. specify 'descend' if you want descending order. sortIndices hold the sorted indices of the array elements, which are row indices of the elements of sortOut in the original array

- [sortOut, sortIndices] = sortrows(inArray, colRef) - sorts array based on values in column colRef while keeping the rows together. Bases on first column by default.

- isequal(inArray1, inarray2, ..., inArrayN)

- isequaln(inArray1, inarray2, ..., inarrayn)

- arrayChar = ischar(inArray) - ischar tests if the input is a character array.

- arrayLogical = islogical(inArray) - islogical tests for logical array.

- arrayNumeric = isnumeric(inArray) - isnumeric tests for numeric array.

- arrayInteger = isinteger(inArray) - isinteger tests whether the input is integer type (Ex: uint8, uint16, ...)

- arrayFloat = isfloat(inArray) - isfloat tests for floating-point array.

- arrayReal= isreal(inArray) - isreal tests for real array.

- objIsa = isa(obj,ClassName) - isa determines whether input obj is an object of specified class ClassName.

- arrayScalar = isscalar(inArray) - isscalar tests for scalar type.

- arrayVector = isvector(inArray) - isvector tests for a vector (a 1D row or column array).

- arrayColumn = iscolumn(inArray) - iscolumn tests for column 1D arrays.

- arrayMatrix = ismatrix(inArray) - ismatrix returns true for a scalar or array up to 2D, but false for an array of more than 2 dimensions.

- arrayEmpty = isempty(inArray) - isempty tests whether inArray is empty.

- primeArray = isprime(inArray) - isprime returns a logical array primeArray, of the same size as inArray. The value at primeArray(index) is true when inArray(index) is a prime number. Otherwise, the values are false.

- finiteArray = isfinite(inArray) - isfinite returns a logical array finiteArray, of the same size as inArray. The value at finiteArray(index) is true when inArray(index) is finite. Otherwise, the values are false.

- infiniteArray = isinf(inArray) - isinf returns a logical array infiniteArray, of the same size as inArray. The value at infiniteArray(index) is true when inArray(index) is infinite. Otherwise, the values are false.

- nanArray = isnan(inArray) - isnan returns a logical array nanArray, of the same size as inArray. The value at nanArray(index) is true when inArray(index) is NaN. Otherwise, the values are false.

- allNonzero = all(inArray) - all identifies whether all array elements are non-zero (true). Instead of testing elements along the columns, all(inArray, 2) tests along the rows. all(inArray,1) is equivalent to all(inArray).

- anyNonzero = any(inArray) - any identifies whether any array elements are non-zero (true), and false otherwise. Instead of testing elements along the columns, any(inArray, 2) tests along the rows. any(inArray,1) is equivalent to any(inArray).

- logicArray = ismember(inArraySet,areElementsMember) - ismember returns a logical array logicArray the same size as inArraySet. The values at logicArray(i) are true where the elements of the first array inArraySet are found in the second array areElementsMember. Otherwise, the values are false. Similar values found by ismember can be extracted with inArraySet(logicArray).

- any(x) - Returns true if x is nonzero; otherwise, returns false.

- isnan(x) - Returns true if x is NaN (Not-a-Number); otherwise, returns false.

- isfinite(x) - Returns true if x is finite; otherwise, returns false. Ex: isfinite(Inf) is false, and isfinite(10) is true.

- isinf(x) - Returns true if x is +Inf or -Inf; otherwise, returns false.

Relational Operators

a & b, and(a, b)

a | b, or(a, b)

~a, not(a)

xor(a, b)

- fctName = @(arglist) expression - anonymous function

- nargin - keyword returns the number of input arguments passed to the function.

Looping

while condition

% code

end

for index = startVal:endVal

% code

end

- continue: Skips the rest of the current loop iteration and begins the next iteration.

- break: Exits a loop before it has finished all iterations.

switch expression

case value1

% code

case value2

% code

otherwise

% code

end

Comprehensive Overview (may repeat)

Built in functions/constants

abs(x) - absolute value

pi - 3.1415...

inf - ∞

eps - floating point accuracy 1e6 106

sum(x) - sums elements in x

cumsum(x) - Cumulative sum

prod - Product of array elements cumprod(x) cumulative product

diff - Difference of elements round/ceil/fix/floor Standard functions..

*Standard functions: sqrt, log, exp, max, min, Bessel *Factorial(x) is only precise for x < 21

Variable Generation

j:k - row vector

j:i:k - row vector incrementing by i

linspace(a,b,n) - n points linearly spaced and including a and b

NaN(a,b) - axb matrix of NaN values

ones(a,b) - axb matrix with all 1 values

zeros(a,b) - axb matrix with all 0 values

meshgrid(x,y) - 2d grid of x and y vectors

global x

Ch. 11 - Custom Functions

function [ outputArgs ] = MainFunctionName (inputArgs)

% statements go here

end

function [ outputArgs ] = LocalFunctionName (inputArgs)

% statements go here

end

- You are allowed to have nested functions in MATLAB

Anonymous Function:

- fctName = @(argList) expression

- Ex: RaisedCos = @(angle) (cosd(angle))^2;

- global variables - can be accessed from anywhere in the file

- Persistent variables

- persistent variable - only known to function where it was declared, maintains value between calls to function.

- Recursion - base case, decreasing case, ending case

- nargin - evaluates to the number of arguments the function was called with

Ch. 12 - Plotting

- plot(xArray, yArray)

- refer to help plot for more extensive documentation, chapter 12 only briefly covers plotting

plot - Line plot

yyaxis - Enables plotting with y-axes on both left and right sides

loglog - Line plot with logarithmic x and y axes

semilogy - Line plot with linear x and logarithmic y axes

semilogx - Line plot with logarithmic x and linear y axes

stairs - Stairstep graph

axis - sets the aspect ratio of x and y axes, ticks etc.

grid - adds a grid to the plot

gtext - allows positioning of text with the mouse

text - allows placing text at specified coordinates of the plot

xlabel labels the x-axis

ylabel labels the y-axis

title sets the graph title

figure(n) makes figure number n the current figure

hold on allows multiple plots to be superimposed on the same axes

hold off releases hold on current plot and allows a new graph to be drawn

close(n) closes figure number n

subplot(a, b, c) creates an a x b matrix of plots with c the current figure

orient specifies the orientation of a figure

Animated plot example:

for j = 1:360

pause(0.02)

plot3(x(j),y(j),z(j),'O')

axis([minx maxx miny maxy minz maxz]);

hold on;

end

Ch. 13 - Strings

stringArray = string(inputArray) - converts the input array inputArray to a string array

number = strLength(stringIn) - returns the number of characters in the input string

stringArray = strings(n, m) - returns an n-by-m array of strings with no characters,

- doing strings(sz) returns an array of strings with no characters, where sz defines the size.

charVec1 = char(stringScalar) char(stringScalar) converts the string scalar stringScalar into a character vector charVec1.

charVec2 = char(numericArray) char(numericArray) converts the numeric array numericArray into a character vector charVec2 corresponding to the Unicode transformation format 16 (UTF-16) code.

stringOut = string1 + string2 - combines the text in both strings

stringOut = join(textSrray) - consecutive elements of array joined, placing a space character between them.

stringOut = blanks(n) - creates a string of n blank characters

stringOut = strcar(string1, string2) - horizontally concatenates strings in arrays.

sprintf(formatSpec, number) - for printing out strings

- strExp = sprintf("%0.6e", pi)

stringArrayOur = compose(formatSpec, arrayIn) - formats data in arrayIn.

lower(string) - converts to lowercase

upper(string) - converts to uppercase

num2str(inputArray, precision) - returns a character vector with the maximum number of digits specified by precision

mat2str(inputMat, precision), converts matrix into a character vector.

numberOut = sscanf(inputText, format) - convert inputText according to format specifier

str2double(inputText)

str2num(inputChar)

strcmp(string1, string2)

strcmpi(string1, string2) - case-insensitive comparison

strncmp(str1, str2, n) - first n characters

strncmpi(str1, str2, n) - case-insensitive comparison of first n characters.

isstring(string) - logical output

isStringScalar(string) - logical output

ischar(inputVar) - logical output

iscellstr(inputVar) - logical output.

isstrprop(stringIn, categoryString) - returns a logical array of the same size as stringIn, with true at indices where elements of the stringIn belong to specified category:

iskeyword(stringIn) - returns true if string is a keyword in the matlab language

isletter(charVecIn)

isspace(charVecIn)

ischar(charVecIn)

contains(string1, testPattern) - boolean outputs if string contains a specific pattern

startsWith(string1, testPattern) - also logical output

endsWith(string1, testPattern) - also logical output

strfind(stringIn, pattern) - returns INDEX of each occurence in array

number = count(stringIn, patternSeek) - returns the number of occurences of string scalar in the string scalar stringIn.

strip(strArray) - removes all consecutive whitespace characters from begining and end of each string in Array, with side argument 'left', 'right', 'both'.

pad(stringIn) - pad with whitespace characters, can also specify where.

replace(stringIn, oldStr, newStr) - replaces all occurrences of oldStr in string array stringIn with newStr.

replaceBetween(strIn, startStr, endStr, newStr)

strrep(origStr, oldSubsr, newSubstr) - searches original string for substric, and if found, replace with new substric.

insertAfter(stringIn, startStr, newStr) - insert a new string afte the substring specified by startStr.

insertBefore(stringIn, endPos, newStr)

extractAfter(stringIn, startStr)

extractBefore(stringIn, startPos)

split(stringIn, delimiter) - divides string at whitespace characters.

splitlines(stringIn, delimiter)

It's frustrating when a long function or script runs and prints unexpected outputs to the command window. The line producing those outputs can be difficult to find.

Run this line of code before running the script or function. Execution will pause when the line is hit and the file will open to that line. Outputs that are intentionaly displayed by functions such as disp() or fprintf() will be ignored.

dbstop if unsuppressed output

To turn this off,

dbclear if unsuppressed output

Time to time I need to filll an existing array with NaNs using logical indexing. A trick I discover is using arithmetics rather than filling. It is quite faster in some circumtances

A=rand(10000);

b=A>0.5;

tic; A(b) = NaN; toc

tic; A = A + 0./~b; toc;

If you know trick for other value filling feel free to post.

function drawframe(f)

% Create a figure

figure;

hold on;

axis equal;

axis off;

% Draw the roads

rectangle('Position', [0, 0, 2, 30], 'FaceColor', [0.5 0.5 0.5]); % Left road

rectangle('Position', [2, 0, 2, 30], 'FaceColor', [0.5 0.5 0.5]); % Right road

% Draw the traffic light

trafficLightPole = rectangle('Position', [-1, 20, 1, 0.2], 'FaceColor', 'black'); % Pole

redLight = rectangle('Position', [0, 20, 0.5, 1], 'FaceColor', 'red'); % Red light

yellowLight = rectangle('Position', [0.5, 20, 0.5, 1], 'FaceColor', 'black'); % Yellow light

greenLight = rectangle('Position', [1, 20, 0.5, 1], 'FaceColor', 'black'); % Green light

carBody = rectangle('Position', [2.5, 2, 1, 4], 'Curvature', 0.2, 'FaceColor', 'red'); % Body

leftWheel = rectangle('Position', [2.5, 3.0, 0.2, 0.2], 'Curvature', [1, 1], 'FaceColor', 'black'); % Left wheel

rightWheel = rectangle('Position', [3.3, 3.0, 0.2, 0.2], 'Curvature', [1, 1], 'FaceColor', 'black'); % Right wheel

leftFrontWheel = rectangle('Position', [2.5, 5.0, 0.2, 0.2], 'Curvature', [1, 1], 'FaceColor', 'black'); % Left wheel

rightFrontWheel = rectangle('Position', [3.3, 5.0, 0.2, 0.2], 'Curvature', [1, 1], 'FaceColor', 'black'); % Right wheel

% Set limits

xlim([-1, 8]);

ylim([-1, 35]);

% Animation parameters

carSpeed = 0.5; % Speed of the car

carPosition = 2; % Initial car position

stopPosition = 15; % Position to stop at the traffic light

isStopped = false; % Car is not stopped initially

%Animation loop

for t = 1:100

% Update traffic light: Red for 40 frames, yellow for 10 frames Green for 40 frames

if t <= 40

% Red light on, yellow and green off

set(redLight, 'FaceColor', 'red');

set(yellowLight, 'FaceColor', 'black');

set(greenLight, 'FaceColor', 'black');

elseif t > 40 && t <= 50

% Change to green light

set(redLight, 'FaceColor', 'black');

set(yellowLight, 'FaceColor', 'yellow');

set(greenLight, 'FaceColor', 'black');

else

% Back to red light

set(redLight, 'FaceColor', 'black');

set(yellowLight, 'FaceColor', 'black');

set(greenLight, 'FaceColor', 'green');

isStopped = false; % Allow car to move

end

%Move the car

if ~isStopped

carPosition = carPosition + carSpeed; % Move forward

if carPosition < stopPosition

%do nothing

else

isStopped = true;

end

else

% Gradually stop the car when red

if carPosition > stopPosition

carPosition = carPosition + carSpeed*(1-t/50); % Move backward until it reaches the stop position

end

end

if carPosition >= 25

carPosition = 25;

end

% Update car position

% set(carBody, 'Position', [carPosition, 2, 1, 0.5]);

set(carBody, 'Position', [2.5, carPosition, 1, 4]);

%set(carWindow, 'Position', [carPosition + 0.2, 2.4, 0.6, 0.2]);

%set(leftWheel, 'Position', [carPosition, 1.5, 0.2, 0.2]);

set(leftWheel, 'Position', [2.5, carPosition+1, 0.2, 0.2]);

% set(rightWheel, 'Position', [carPosition + 0.8, 1.5, 0.2, 0.2]);

set(rightWheel, 'Position', [3.3, carPosition+1, 0.2, 0.2]);

set(leftFrontWheel, 'Position', [2.5, carPosition+3, 0.2, 0.2]);

set(rightFrontWheel, 'Position', [3.3, carPosition+3, 0.2, 0.2]);

% Pause to control animation speed

pause(0.01);

end

hold off;

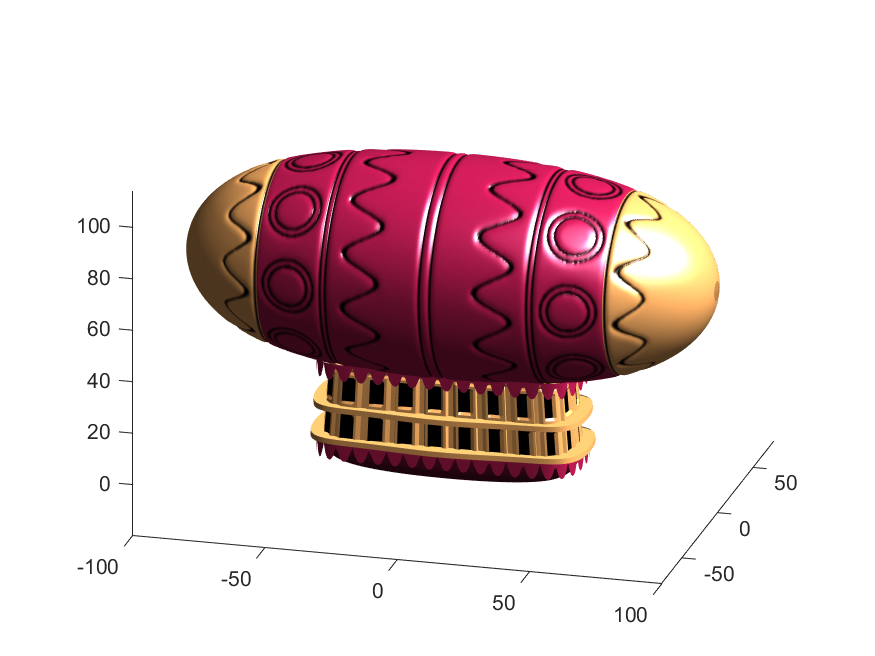

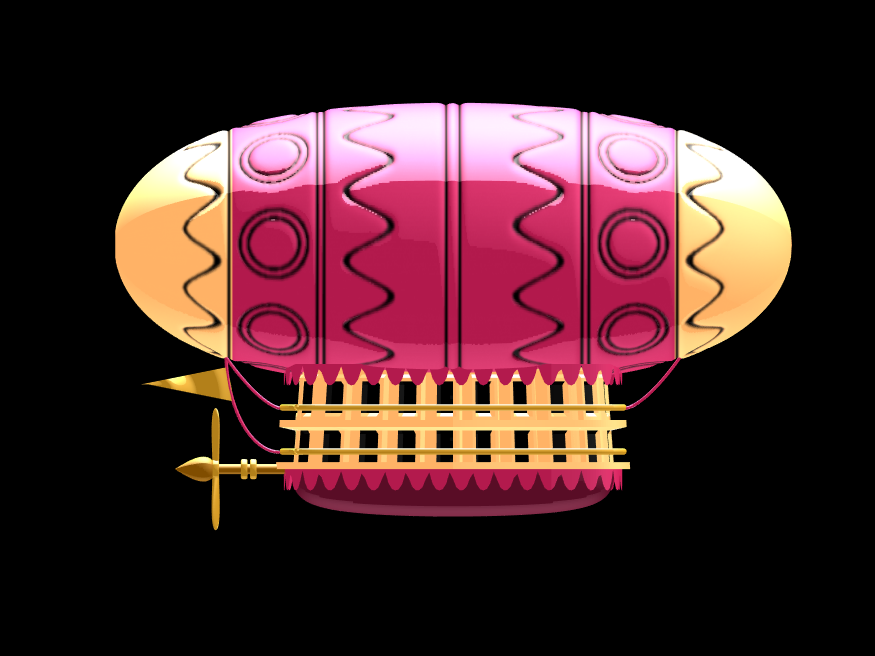

In the spirit of warming up for this year's minihack contest, I'm uploading a walkthrough for how to design an airship using pure Matlab script. This is commented and uncondensed; half of the challenge for the minihacks is how minimize characters. But, maybe it will give people some ideas.

The actual airship design is from one of my favorite original NES games that I played when I was a kid - Little Nemo: The Dream Master. The design comes from the intro of the game when Nemo sees the Slumberland airship leave for Slumberland:

(Snip from a frame of the opening scene in Capcom's game Little Nemo: The Dream Master, showing the Slumberland airship).

I spent hours playing this game with my two sisters, when we were little. It's fun and tough, but the graphics sparked the imagination. On to the code walkthrough, beginning with the color palette: these four colors are the only colors used for the airship:

c1=cat(3,1,.7,.4); % Cream color

c2=cat(3,.7,.1,.3); % Magenta

c3=cat(3,0.7,.5,.1); % Gold

c4=cat(3,.5,.3,0); % bronze

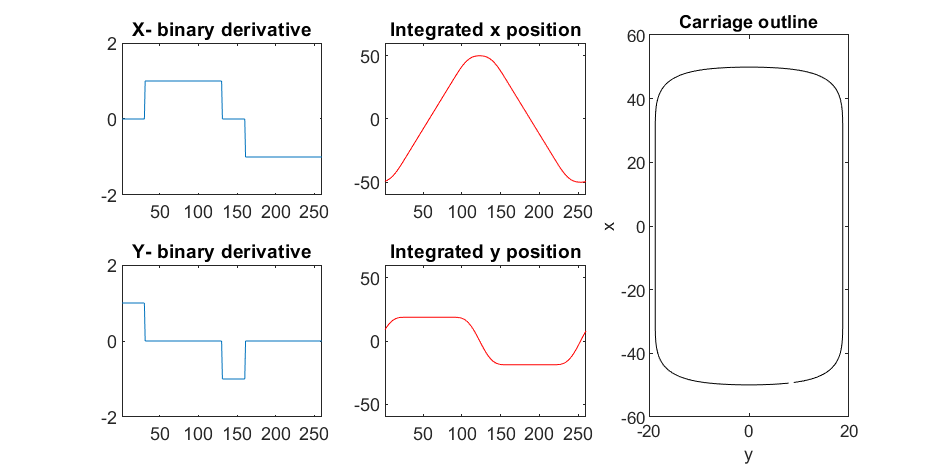

We start with the airship carriage body. We want something rectangular but smoothed on the corners. To do this we are going to start with the separate derivatives of the x and y components, which can be expressed using separate blocks of only three levels: [1, 0, -1]. You could integrate to create a rectangle, but if we smooth the derivatives prior to integrating we will get rounded edges. This is done in the following code:

% Binary components for x & y vectors

z=zeros(1,30);

o=ones(1,100);

% X and y vectors

x=[z,o,z,-o];

y=[1+z,1-o,z-1,1-o];

% Smoother function (fourier / circular)

s=@(x)ifft(fft(x).*conj(fft(hann(45)'/22,260)));

% Integrator function with replication and smoothing to form mesh matrices

u=@(x)repmat(cumsum(s(x)),[30,1]);

% Construct x and y components of carriage with offsets

x3=u(x)-49.35;

y3=u(y)+6.35;

y3 = y3*1.25; % Make it a little fatter

% Add a z-component to make the full set of matrices for creating a 3D

% surface:

z3=linspace(0,1,30)'.*ones(1,260)*30;

z3(14,:)=z3(15,:); % These two lines are for adding platforms

z3(2,:)=z3(3,:); % to the carriage, later.

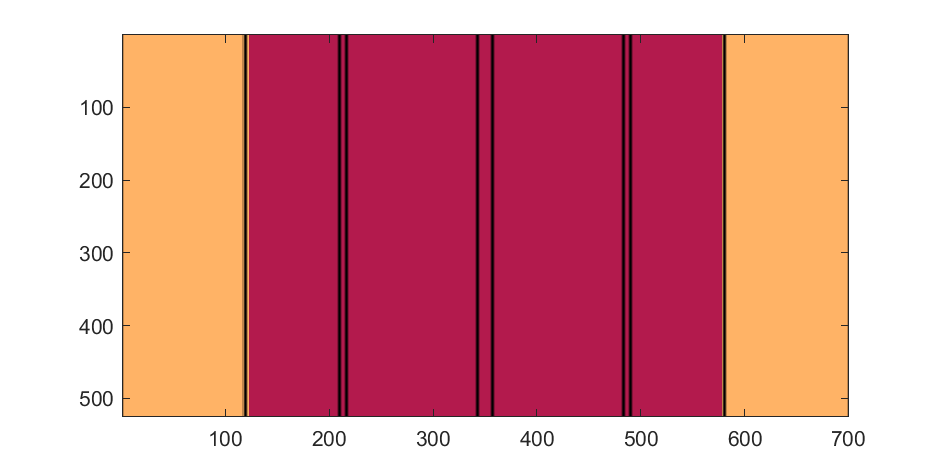

Plotting x, y, and the top row of the smoothed, integrated, and replicated matrices x3 and y3 gives the following:

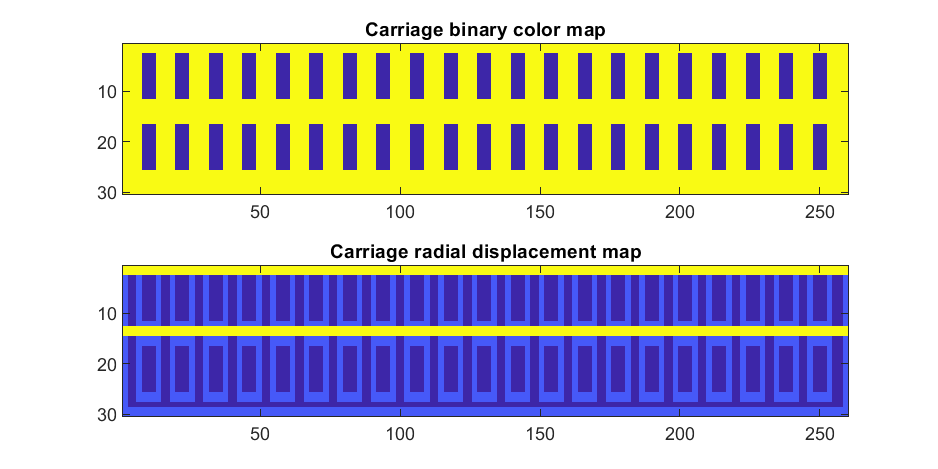

We now have the x and y components for a 3D mesh of the carriage, let's make it more interesting by adding a color scheme including doors, and texture for the trim around the doors. Let's also add platforms beneath the doors for passengers to walk on.

Starting with the color values, let's make doors by convolving points in a color-matrix by a door shaped function.

m=0*z3; % Image matrix that will be overlayed on carriage surface

m(7,10:12:end)=1; % Door locations (lower deck)

m(21,10:12:end)=1; % Door locations (upper deck)

drs = ones(9, 5); % Door shape

m=1-conv2(m,ones(9,5),'same'); % Applying

To add the trim, we will convolve matrix "m" (the color matrix) with a square function, and look for values that lie between the extrema. We will use this to create a displacement function that bumps out the -x, and -y values of the carriage surface in intermediary polar coordinate format.

rm=conv2(m,ones(5)/25,'same'); % Smoothing the door function

rm(~m)=0; % Preserving only the region around the doors

rds=0*m; % Radial displacement function

rds(rm<1&rm>0)=1; % Preserving region around doors

rds(m==0)=0;

rds(13:14,:)=6; % Adding walkways

rds(1:2,:)=6;

% Apply radial displacement function

[th,rd]=cart2pol(x3,y3);

[x3T,y3T]=pol2cart(th,(rd+rds)*.89);

If we plot the color function (m) and radial displacement function (rds) we get the following:

In the upper plot you can see the doors, and in the bottom map you can see the walk way and door trim.

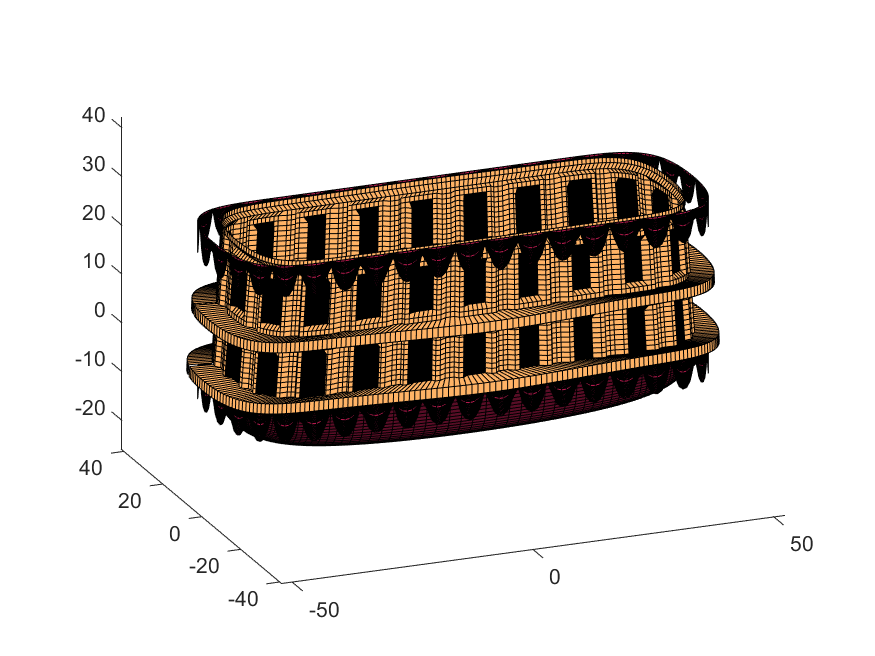

Next, we are going to add some flags draped from the bottom and top of the carriage. We are going to recycle the values in "z3" to do this, by multiplying that matrix with the absolute value of a sine-wave, squished a bit with the soft-clip erf() function.

We add a keel to the airship carriage using a canonical sphere turned on its side, again using the soft-clip erf() function to make it roughly rectangular in x and y, and multiplying with a vector that is half nan's to make the top half transparent.

At this point, since we are beginning the plotting of the ship, we also need to create our hgtransform objects. These allow us to move all of the components of the airship in unison, and also link objects with pivot points to the airship, such as the propeller.

% Now we need some flags extending around the top and bottom of the

% carriage. We can do this my multiplying the height function (z3) with the

% absolute value of a sine-wave, rounded with a compression function

% (erf() in this case);

g=-z3.*erf(abs(sin(linspace(0,40*pi,260))))/4; % Flags

% Also going to add a slight taper to the carriage... gives it a nice look

tp=linspace(1.05,1,30)';

% Finally, plotting. Plot the carriage with the color-map for the doors in

% the cream color, than the flags in magenta. Attach them both to transform

% objects for movement.

% Set up transform objects. 2 moving parts:

% 1) The airship itself and all sub-components

% 2) The propellor, which attaches to the airship and spins on its axis.

hold on;

P=hgtransform('Parent',gca); % Ship

S=hgtransform('Parent',P); % Prop

surf(x3T.*tp,y3T,z3,c1.*m,'Parent',P);

surf(x3,y3,g,c2.*rd./rd, 'Parent', P);

surf(x3,y3,g+31,c2.*rd./rd, 'Parent', P);

axis equal

% Now add the keel of the airship. Will use a canonical sphere and the

% erf() compression function to square off.

[x,y,z]=sphere(99);

mk=round(linspace(-1,1).^2+.3); % This function makes the top half of the sphere nan's for transparency.

surf(50*erf(1.4*z),15*erf(1.4*y),13*x.*mk./mk-1,.5*c2.*z./z, 'Parent', P);

% The carriage is done. Now we can make the blimp above it.

We haven't adjusted the shading of the image yet, but you can see the design features that have been created:

Next, we start working on the blimp. This is going to use a few more vertices & faces. We are going to use a tapered cylinder for this part, and will start by making the overlaid image, which will have 2 colors plus radial rings, circles, and squiggles for ornamentation.

M=525; % Blimp (matrix dimensions)

N=700;

% Assign the blimp the cream and magenta colors

t=122; % Transition point

b=ones(M,N,3); % Blimp color map template

bc=b.*c1; % Blimp color map

bc(:,t+1:end-t,:)=b(:,t+1:end-t,:).*c2;

% Add axial rings around blimp

l=[.17,.3,.31,.49];

l=round([l,1-fliplr(l)]*N); % Mirroring

lnw=ones(1,N); % Mask

lnw(l)=0;

lnw=rescale(conv(lnw,hann(7)','same'));

bc=bc.*lnw;

% Now add squiggles. We're going to do this by making an even function in

% the x-dimension (N, 725) added with a sinusoidal oscillation in the

% y-dimension (M, 500), then thresholding.

r=sin(linspace(0, 2*pi, M)*10)'+(linspace(-1, 1, N).^6-.18)*15;

q=abs(r)>.15;

r=sin(linspace(0, 2*pi, M)*12)'+(abs(linspace(-1, 1, N))-.25)*15;

q=q.*(abs(r)>.15);

% Now add the circles on the blimp. These will be spaced evenly in the

% polar angle dimension around the axis. We will have 9. To make the

% circles, we will create a cone function with a peak at the center of the

% circle, and use thresholding to create a ring of appropriate radius.

hs=[1,.75,.5,.25,0,-.25,-.5,-.75,-1]; % Axial spacing of rings

% Cone generation and ring loop

xy= @(h,s)meshgrid(linspace(-1, 1, N)+s*.53,(linspace(-1, 1, M)+h)*1.15);

w=@(x,y)sqrt(x.^2+y.^2);

for n=1:9

h=hs(n);

[xx,yy]=xy(h,-1);

r1=w(xx,yy);

[xx,yy]=xy(h,1);

r2=w(xx,yy);

b=@(x,y)abs(y-x)>.005;

q=q.*b(.1,r1).*b(.075,r1).*b(.1,r2).*b(.075,r2);

end

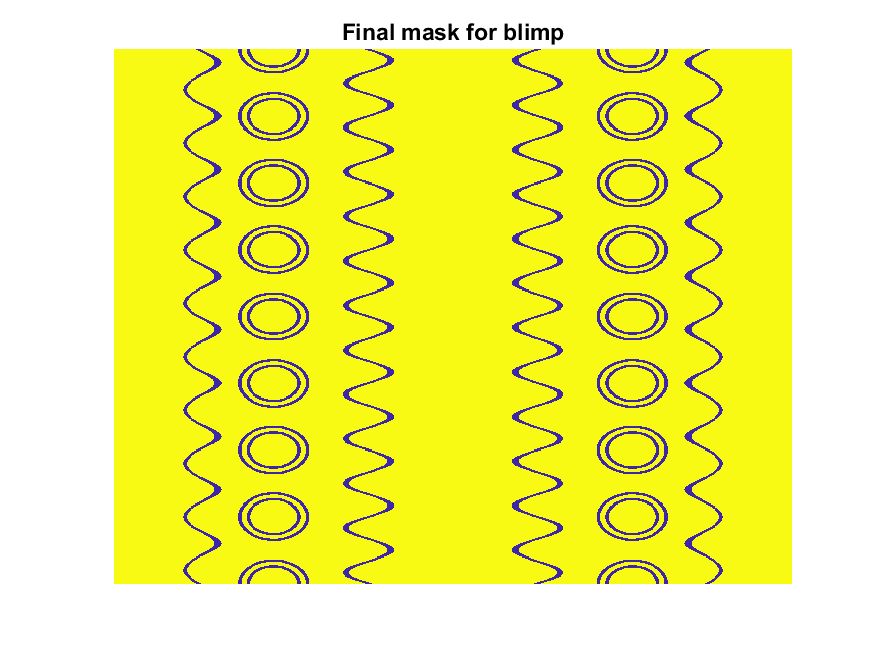

The figures below show the color scheme and mask used to apply the squiggles and circles generated in the code above:

Finally, for the colormap we are going to smooth the binary mask to avoid hard transitions, and use it to to add a "puffy" texture to the blimp shape. This will be done by diffusing the mask iteratively in a loop with a non-linear min() operator.

% 2D convolution function

ff=@(x)circshift(ifft2(fft2(x).*conj(fft2(hann(7)*hann(7)'/9,M,N))),[3,3]);

q=ff(q); % Smooth our mask function

hh=rgb2hsv(q.*bc); % Convert to hsv: we are going to use the value

% component for radial displacement offsets of the

% 3D blimp structure.

rd=hh(:,:,3); % Value component

for n=1:10

rd=min(rd,ff(rd)); % Diffusing the value component for a puffy look

end

rd=(rd+35)/36; % Make displacements effects small

% Now make 3D blimp manifold using "cylinder" canonical shape

[x,y,z]=cylinder(erf(sin(linspace(0,pi,N)).^.5)/4,M-1); % First argument is the blimp taper

[t,r]=cart2pol(x, y);

[x2,y2]=pol2cart(t, r.*rd'); % Applying radial displacment from mask

s=200;

% Plotting the blimp

surf(z'*s-s/2, y2'*s, x2'*s+s/3.9+15, q.*bc,'Parent',P);

Notice that the parent of the blimp surface plot is the same as the carriage (e.g. hgtransform object "P"). Plotting at this point using flat shading and adding some lighting gives the image below:

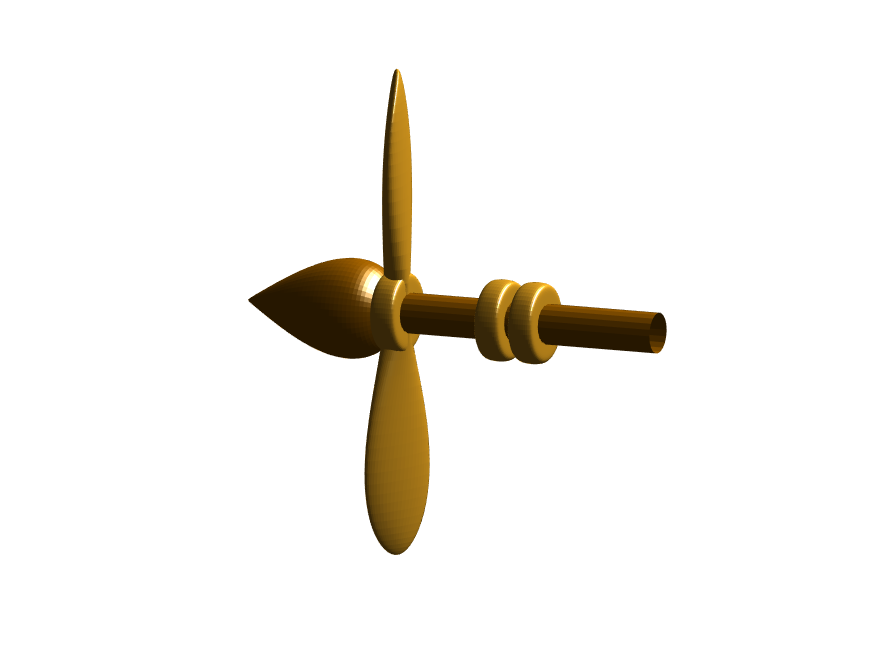

Next, we need to add a propeller so it can move. This will include the creation of a shaft using the cylinder() function. The rest of the pieces (the propeller blades, collars and shaft tip) all use the same canonical sphere with distortions applied using various math functions. Note that when the propeller is made it is linked to hgtransform object "S" rather than "P." This will allow the propeller to rotate, but still be joined to the airship.

% Next, the propeller. First, we start with the shaft. This is a simple

% cylinder. We add an offset variable and a scale variable to move our

% propeller components around, as well.

shx = -70; % This is our x-shifter for components

scl = 3; % Component size scaler

[x,y,z]=cylinder(1, 20); % Canonical cylinder for prop shaft.

p(1)=surf(-scl*(z-1)*7+shx,scl*x/2,scl*y/2,0*x+c4,'Parent',P); % Prop shaft

% Now the propeller. This is going to be made from a distorted sphere.

% The important thing here is that it is linked to the "S" hgtransform

% object, which will allow it to rotate.

[x,y,z]=sphere(50);

a=(-1:.04:1)';

x2=(x.*cos(a)-y/3.*sin(a)).*(abs(sin(a*2))*2+.1);

y2=(x.*sin(a)+y/3.*cos(a));

p(2)=surf(-scl*y2+shx,scl*x2,scl*z*6,0*x+c3,'Parent',S);

% Now for the prop-collars. You can see these on the shaft in the NES

% animation. These will just be made by using the canonical sphere and the

% erf() activation function to square it in the x-dimension.

g=erf(z*3)/3;

r=@(g)surf(-scl*g+shx,scl*x,scl*y,0*x+c3,'Parent',P);

r(g);

r(g-2.8);

r(g-3.7);

% Finally, the prop shaft tip. This will just be the sphere with a

% taper-function applied radially.

t=1.7*cos(0:.026:1.3)'.^2;

p(3)=surf(-(z*2+2)*scl + shx,x.*t*scl,y.*t*scl, 0*x+c4,'Parent',P);

Now for some final details including the ropes to the blimp, a flag hung on one of the ropes, and railings around the walkways so that passengers don't plummet to their doom. This will make use of the ad-hoc "ropeG" function, which takes a 3D vector of points and makes a conforming cylinder around it, so that you get lighting functions etc. that don't work on simple lines. This function is added to the script at the end to do this:

% Rope function for making a 3D curve have thickness, like a rope.

% Inputs:

% - xyz (3D curve vector, M points in 3 x M format)

% - N (Number of radial points in cylinder function around the curve

% - W (Width of the rope)

%