ans =

Contenuto principale

Results for

We're excited to announce that the 2024 Community Contest—MATLAB Shorts Mini Hack starts today! The contest will run for 5 weeks, from Oct. 7th to Nov. 10th.

What creative short movies will you create? Let the party begin, and we look forward to seeing you all in the contest!

What is the side-effect of counting the number of Deep Learning Toolbox™ updates in the last 5 years? The industry has slowly stabilised and matured, so updates have slowed down in the last 1 year, and there has been no exponential growth.Is it correct to assume that? Let's see what you think!

releaseNumNames = "R"+string(2019:2024)+["a";"b"];

releaseNumNames = releaseNumNames(:);

numReleaseNotes = [10,14,27,39,38,43,53,52,55,57,46,46];

exampleNums = [nan,nan,nan,nan,nan,nan,40,24,22,31,24,38];

bar(releaseNumNames,[numReleaseNotes;exampleNums]')

legend(["#release notes","#new/update examples"],Location="northwest")

title("Number of Deep Learning Toolbox™ update items in the last 5 years")

ylabel("#release notes")

Dear contest participants,

The 2024 Community Contest—MATLAB Shorts Mini Hack—is just one week away! Last year, we challenged you to create a 48-frame, 2-second animation. This year, we're doubling the fun by increasing the frame count to 96 and adding audio support. Your mission? Create a short movie!

As always, whether you are a seasoned MATLAB user or just a beginner, you can participate in the contest and have opportunities to win amazing prizes.

Timeframe:

- The contest will run for 5 weeks, from Oct. 7th to Nov. 10th, Eastern Time.

General Rules:

- The first week is dedicated to entry creation, and the fifth week is reserved for voting only.

- Create a 96-frame, 4-second animation and add audio. We will loop it 3 times to create a 12-second short movie for you.

- The character limit remains at 2,000 characters.

Prizes

- You will have opportunities to win compelling prizes, including Amazon gift cards, MathWorks T-shirts, and virtual badges. We will give out both weekly prizes and grand prizes.

Warm-up!

With one week left before the contest begins, we recommend you warm up by reading a fantastic article: Walkthrough: making Little Nemo's airship in MATLAB by @Tim. The article shares both technical insights and the challenges encountered along the way.

The MATLAB Central Community Team

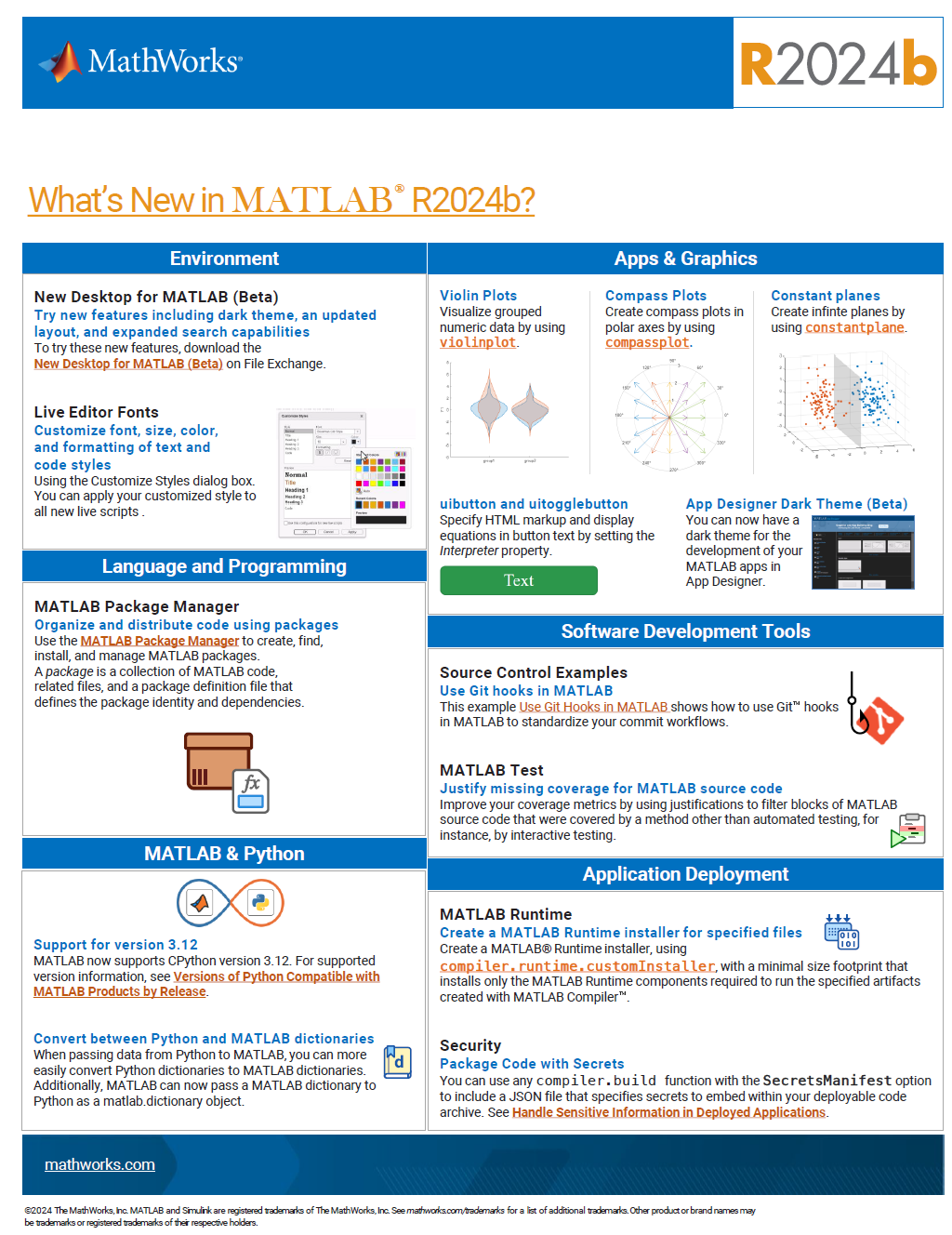

See the attached PDF for a higher resolution

Related blogs posts:

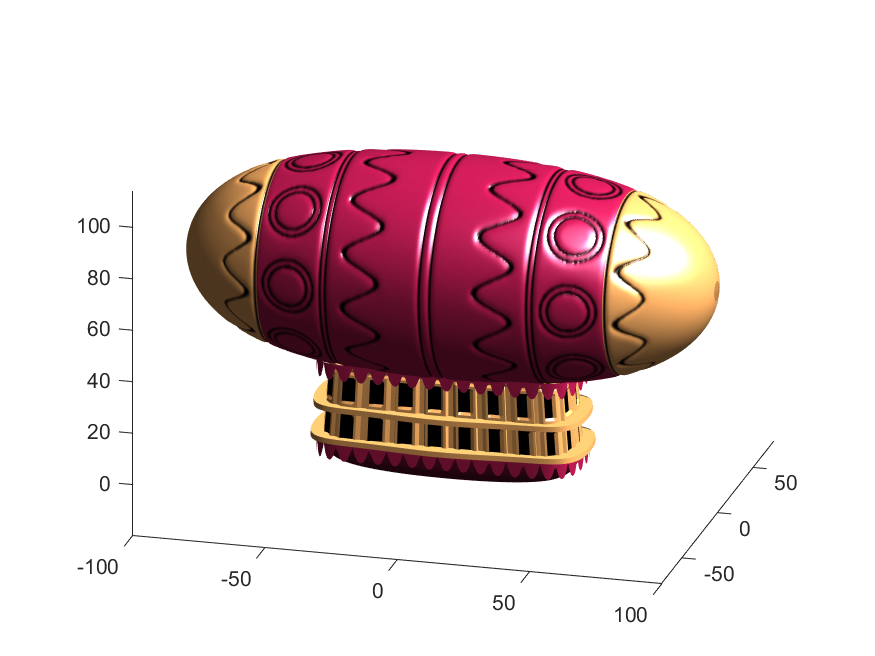

In the spirit of warming up for this year's minihack contest, I'm uploading a walkthrough for how to design an airship using pure Matlab script. This is commented and uncondensed; half of the challenge for the minihacks is how minimize characters. But, maybe it will give people some ideas.

The actual airship design is from one of my favorite original NES games that I played when I was a kid - Little Nemo: The Dream Master. The design comes from the intro of the game when Nemo sees the Slumberland airship leave for Slumberland:

(Snip from a frame of the opening scene in Capcom's game Little Nemo: The Dream Master, showing the Slumberland airship).

I spent hours playing this game with my two sisters, when we were little. It's fun and tough, but the graphics sparked the imagination. On to the code walkthrough, beginning with the color palette: these four colors are the only colors used for the airship:

c1=cat(3,1,.7,.4); % Cream color

c2=cat(3,.7,.1,.3); % Magenta

c3=cat(3,0.7,.5,.1); % Gold

c4=cat(3,.5,.3,0); % bronze

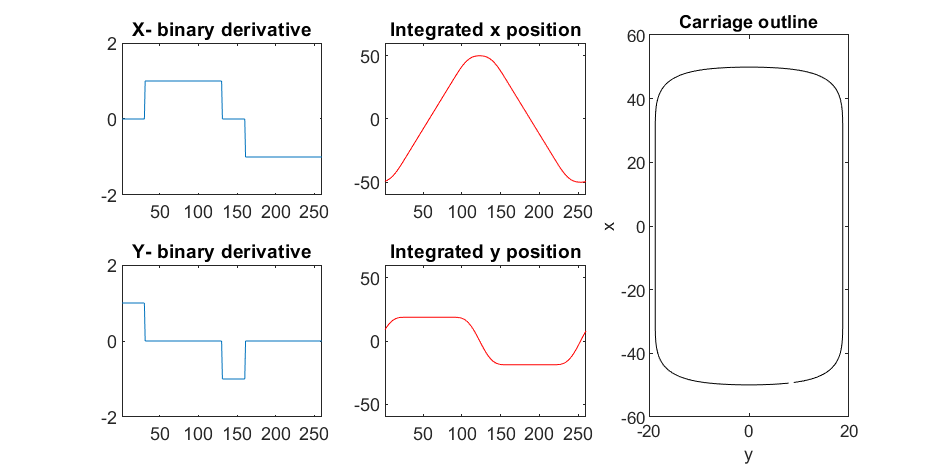

We start with the airship carriage body. We want something rectangular but smoothed on the corners. To do this we are going to start with the separate derivatives of the x and y components, which can be expressed using separate blocks of only three levels: [1, 0, -1]. You could integrate to create a rectangle, but if we smooth the derivatives prior to integrating we will get rounded edges. This is done in the following code:

% Binary components for x & y vectors

z=zeros(1,30);

o=ones(1,100);

% X and y vectors

x=[z,o,z,-o];

y=[1+z,1-o,z-1,1-o];

% Smoother function (fourier / circular)

s=@(x)ifft(fft(x).*conj(fft(hann(45)'/22,260)));

% Integrator function with replication and smoothing to form mesh matrices

u=@(x)repmat(cumsum(s(x)),[30,1]);

% Construct x and y components of carriage with offsets

x3=u(x)-49.35;

y3=u(y)+6.35;

y3 = y3*1.25; % Make it a little fatter

% Add a z-component to make the full set of matrices for creating a 3D

% surface:

z3=linspace(0,1,30)'.*ones(1,260)*30;

z3(14,:)=z3(15,:); % These two lines are for adding platforms

z3(2,:)=z3(3,:); % to the carriage, later.

Plotting x, y, and the top row of the smoothed, integrated, and replicated matrices x3 and y3 gives the following:

We now have the x and y components for a 3D mesh of the carriage, let's make it more interesting by adding a color scheme including doors, and texture for the trim around the doors. Let's also add platforms beneath the doors for passengers to walk on.

Starting with the color values, let's make doors by convolving points in a color-matrix by a door shaped function.

m=0*z3; % Image matrix that will be overlayed on carriage surface

m(7,10:12:end)=1; % Door locations (lower deck)

m(21,10:12:end)=1; % Door locations (upper deck)

drs = ones(9, 5); % Door shape

m=1-conv2(m,ones(9,5),'same'); % Applying

To add the trim, we will convolve matrix "m" (the color matrix) with a square function, and look for values that lie between the extrema. We will use this to create a displacement function that bumps out the -x, and -y values of the carriage surface in intermediary polar coordinate format.

rm=conv2(m,ones(5)/25,'same'); % Smoothing the door function

rm(~m)=0; % Preserving only the region around the doors

rds=0*m; % Radial displacement function

rds(rm<1&rm>0)=1; % Preserving region around doors

rds(m==0)=0;

rds(13:14,:)=6; % Adding walkways

rds(1:2,:)=6;

% Apply radial displacement function

[th,rd]=cart2pol(x3,y3);

[x3T,y3T]=pol2cart(th,(rd+rds)*.89);

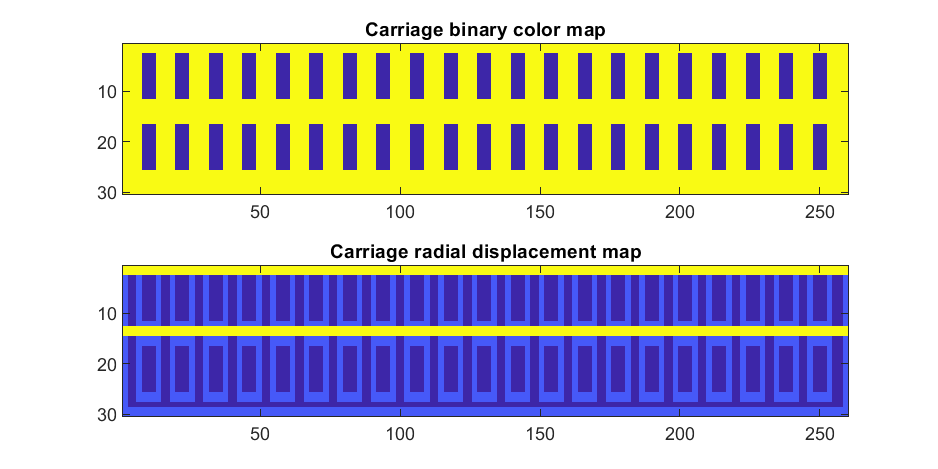

If we plot the color function (m) and radial displacement function (rds) we get the following:

In the upper plot you can see the doors, and in the bottom map you can see the walk way and door trim.

Next, we are going to add some flags draped from the bottom and top of the carriage. We are going to recycle the values in "z3" to do this, by multiplying that matrix with the absolute value of a sine-wave, squished a bit with the soft-clip erf() function.

We add a keel to the airship carriage using a canonical sphere turned on its side, again using the soft-clip erf() function to make it roughly rectangular in x and y, and multiplying with a vector that is half nan's to make the top half transparent.

At this point, since we are beginning the plotting of the ship, we also need to create our hgtransform objects. These allow us to move all of the components of the airship in unison, and also link objects with pivot points to the airship, such as the propeller.

% Now we need some flags extending around the top and bottom of the

% carriage. We can do this my multiplying the height function (z3) with the

% absolute value of a sine-wave, rounded with a compression function

% (erf() in this case);

g=-z3.*erf(abs(sin(linspace(0,40*pi,260))))/4; % Flags

% Also going to add a slight taper to the carriage... gives it a nice look

tp=linspace(1.05,1,30)';

% Finally, plotting. Plot the carriage with the color-map for the doors in

% the cream color, than the flags in magenta. Attach them both to transform

% objects for movement.

% Set up transform objects. 2 moving parts:

% 1) The airship itself and all sub-components

% 2) The propellor, which attaches to the airship and spins on its axis.

hold on;

P=hgtransform('Parent',gca); % Ship

S=hgtransform('Parent',P); % Prop

surf(x3T.*tp,y3T,z3,c1.*m,'Parent',P);

surf(x3,y3,g,c2.*rd./rd, 'Parent', P);

surf(x3,y3,g+31,c2.*rd./rd, 'Parent', P);

axis equal

% Now add the keel of the airship. Will use a canonical sphere and the

% erf() compression function to square off.

[x,y,z]=sphere(99);

mk=round(linspace(-1,1).^2+.3); % This function makes the top half of the sphere nan's for transparency.

surf(50*erf(1.4*z),15*erf(1.4*y),13*x.*mk./mk-1,.5*c2.*z./z, 'Parent', P);

% The carriage is done. Now we can make the blimp above it.

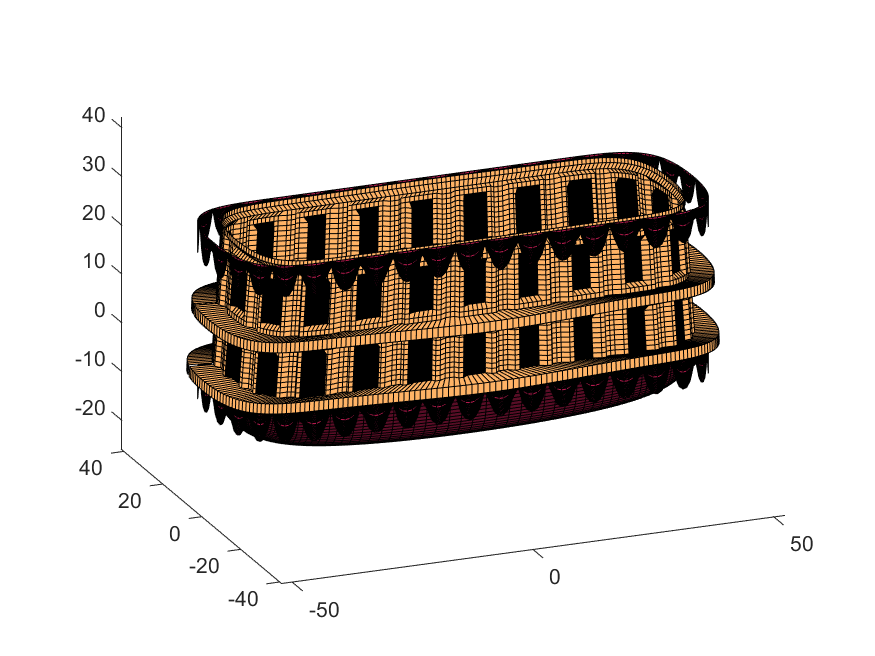

We haven't adjusted the shading of the image yet, but you can see the design features that have been created:

Next, we start working on the blimp. This is going to use a few more vertices & faces. We are going to use a tapered cylinder for this part, and will start by making the overlaid image, which will have 2 colors plus radial rings, circles, and squiggles for ornamentation.

M=525; % Blimp (matrix dimensions)

N=700;

% Assign the blimp the cream and magenta colors

t=122; % Transition point

b=ones(M,N,3); % Blimp color map template

bc=b.*c1; % Blimp color map

bc(:,t+1:end-t,:)=b(:,t+1:end-t,:).*c2;

% Add axial rings around blimp

l=[.17,.3,.31,.49];

l=round([l,1-fliplr(l)]*N); % Mirroring

lnw=ones(1,N); % Mask

lnw(l)=0;

lnw=rescale(conv(lnw,hann(7)','same'));

bc=bc.*lnw;

% Now add squiggles. We're going to do this by making an even function in

% the x-dimension (N, 725) added with a sinusoidal oscillation in the

% y-dimension (M, 500), then thresholding.

r=sin(linspace(0, 2*pi, M)*10)'+(linspace(-1, 1, N).^6-.18)*15;

q=abs(r)>.15;

r=sin(linspace(0, 2*pi, M)*12)'+(abs(linspace(-1, 1, N))-.25)*15;

q=q.*(abs(r)>.15);

% Now add the circles on the blimp. These will be spaced evenly in the

% polar angle dimension around the axis. We will have 9. To make the

% circles, we will create a cone function with a peak at the center of the

% circle, and use thresholding to create a ring of appropriate radius.

hs=[1,.75,.5,.25,0,-.25,-.5,-.75,-1]; % Axial spacing of rings

% Cone generation and ring loop

xy= @(h,s)meshgrid(linspace(-1, 1, N)+s*.53,(linspace(-1, 1, M)+h)*1.15);

w=@(x,y)sqrt(x.^2+y.^2);

for n=1:9

h=hs(n);

[xx,yy]=xy(h,-1);

r1=w(xx,yy);

[xx,yy]=xy(h,1);

r2=w(xx,yy);

b=@(x,y)abs(y-x)>.005;

q=q.*b(.1,r1).*b(.075,r1).*b(.1,r2).*b(.075,r2);

end

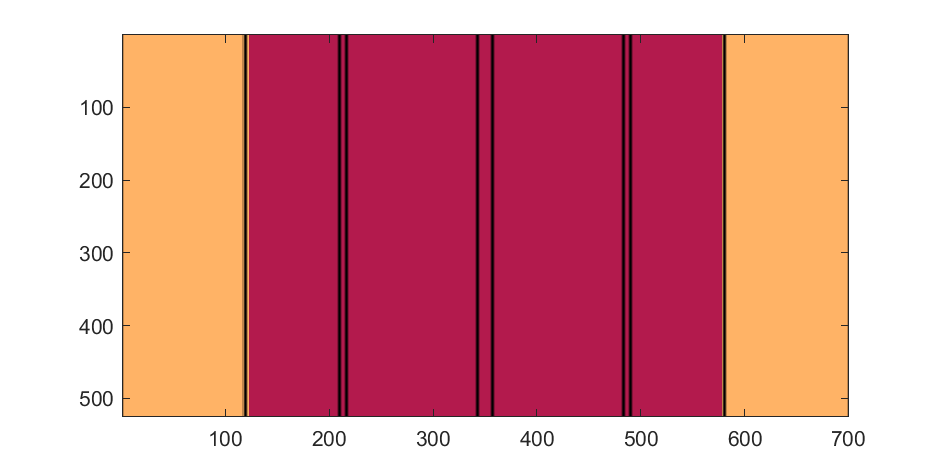

The figures below show the color scheme and mask used to apply the squiggles and circles generated in the code above:

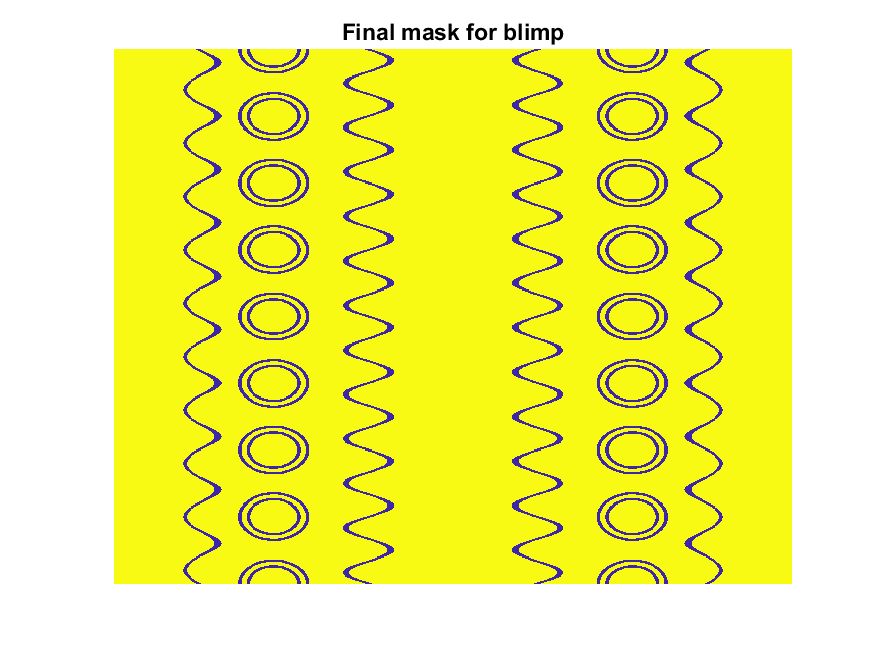

Finally, for the colormap we are going to smooth the binary mask to avoid hard transitions, and use it to to add a "puffy" texture to the blimp shape. This will be done by diffusing the mask iteratively in a loop with a non-linear min() operator.

% 2D convolution function

ff=@(x)circshift(ifft2(fft2(x).*conj(fft2(hann(7)*hann(7)'/9,M,N))),[3,3]);

q=ff(q); % Smooth our mask function

hh=rgb2hsv(q.*bc); % Convert to hsv: we are going to use the value

% component for radial displacement offsets of the

% 3D blimp structure.

rd=hh(:,:,3); % Value component

for n=1:10

rd=min(rd,ff(rd)); % Diffusing the value component for a puffy look

end

rd=(rd+35)/36; % Make displacements effects small

% Now make 3D blimp manifold using "cylinder" canonical shape

[x,y,z]=cylinder(erf(sin(linspace(0,pi,N)).^.5)/4,M-1); % First argument is the blimp taper

[t,r]=cart2pol(x, y);

[x2,y2]=pol2cart(t, r.*rd'); % Applying radial displacment from mask

s=200;

% Plotting the blimp

surf(z'*s-s/2, y2'*s, x2'*s+s/3.9+15, q.*bc,'Parent',P);

Notice that the parent of the blimp surface plot is the same as the carriage (e.g. hgtransform object "P"). Plotting at this point using flat shading and adding some lighting gives the image below:

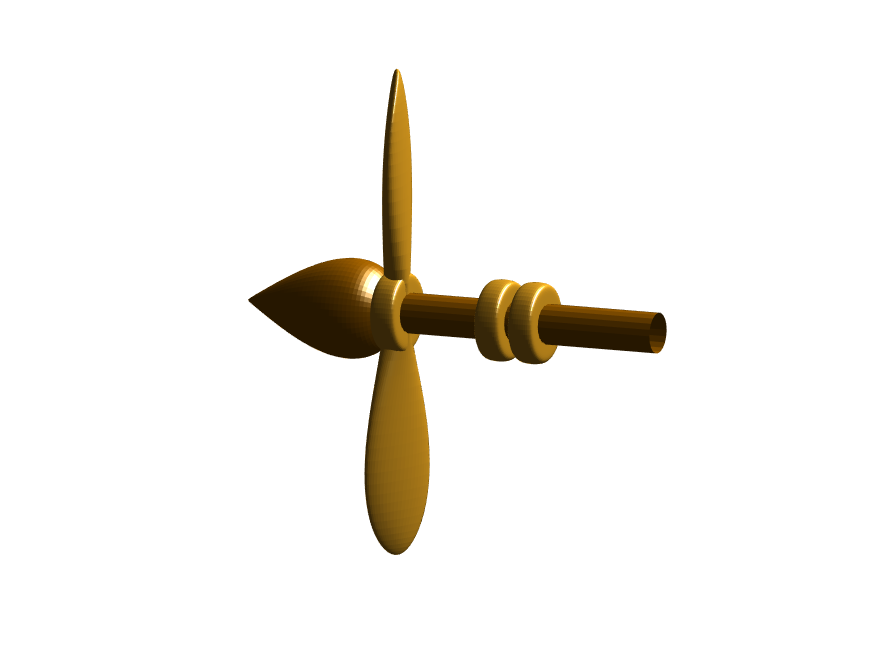

Next, we need to add a propeller so it can move. This will include the creation of a shaft using the cylinder() function. The rest of the pieces (the propeller blades, collars and shaft tip) all use the same canonical sphere with distortions applied using various math functions. Note that when the propeller is made it is linked to hgtransform object "S" rather than "P." This will allow the propeller to rotate, but still be joined to the airship.

% Next, the propeller. First, we start with the shaft. This is a simple

% cylinder. We add an offset variable and a scale variable to move our

% propeller components around, as well.

shx = -70; % This is our x-shifter for components

scl = 3; % Component size scaler

[x,y,z]=cylinder(1, 20); % Canonical cylinder for prop shaft.

p(1)=surf(-scl*(z-1)*7+shx,scl*x/2,scl*y/2,0*x+c4,'Parent',P); % Prop shaft

% Now the propeller. This is going to be made from a distorted sphere.

% The important thing here is that it is linked to the "S" hgtransform

% object, which will allow it to rotate.

[x,y,z]=sphere(50);

a=(-1:.04:1)';

x2=(x.*cos(a)-y/3.*sin(a)).*(abs(sin(a*2))*2+.1);

y2=(x.*sin(a)+y/3.*cos(a));

p(2)=surf(-scl*y2+shx,scl*x2,scl*z*6,0*x+c3,'Parent',S);

% Now for the prop-collars. You can see these on the shaft in the NES

% animation. These will just be made by using the canonical sphere and the

% erf() activation function to square it in the x-dimension.

g=erf(z*3)/3;

r=@(g)surf(-scl*g+shx,scl*x,scl*y,0*x+c3,'Parent',P);

r(g);

r(g-2.8);

r(g-3.7);

% Finally, the prop shaft tip. This will just be the sphere with a

% taper-function applied radially.

t=1.7*cos(0:.026:1.3)'.^2;

p(3)=surf(-(z*2+2)*scl + shx,x.*t*scl,y.*t*scl, 0*x+c4,'Parent',P);

Now for some final details including the ropes to the blimp, a flag hung on one of the ropes, and railings around the walkways so that passengers don't plummet to their doom. This will make use of the ad-hoc "ropeG" function, which takes a 3D vector of points and makes a conforming cylinder around it, so that you get lighting functions etc. that don't work on simple lines. This function is added to the script at the end to do this:

% Rope function for making a 3D curve have thickness, like a rope.

% Inputs:

% - xyz (3D curve vector, M points in 3 x M format)

% - N (Number of radial points in cylinder function around the curve

% - W (Width of the rope)

%

% Outputs:

% - xf, yf, zf (Matrices that can be used with surf())

function [xf, yf, zf] = RopeG(xyz, N, W)

% Canonical cylinder with N points in circumference

[xt,yt,zt] = cylinder(1, N);

% Extract just the first ring and make (W) wide

xyzt = [xt(1, :); yt(1, :); zt(1, :)]*W;

% Get local orientation vector between adjacent points in rope

dxyz = xyz(:, 2:end) - xyz(:, 1:end-1);

dxyz(:, end+1) = dxyz(:, end);

vcs = dxyz./vecnorm(dxyz);

% We need to orient circle so that its plane normal is parallel to

% xyzt. This is a kludgey way to do that.

vcs2 = [ones(2, size(vcs, 2)); -(vcs(1, :) + vcs(2, :))./(vcs(3, :)+0.01)];

vcs2 = vcs2./vecnorm(vcs2);

vcs3 = cross(vcs, vcs2);

p = @(x)permute(x, [1, 3, 2]);

rmats = [p(vcs3), p(vcs2), p(vcs)];

% Create surface

xyzF = pagemtimes(rmats, xyzt) + permute(xyz, [1, 3, 2]);

% Outputs for surf format

xf = squeeze(xyzF(1, :, :));

yf = squeeze(xyzF(2, :, :));

zf = squeeze(xyzF(3, :, :));

end

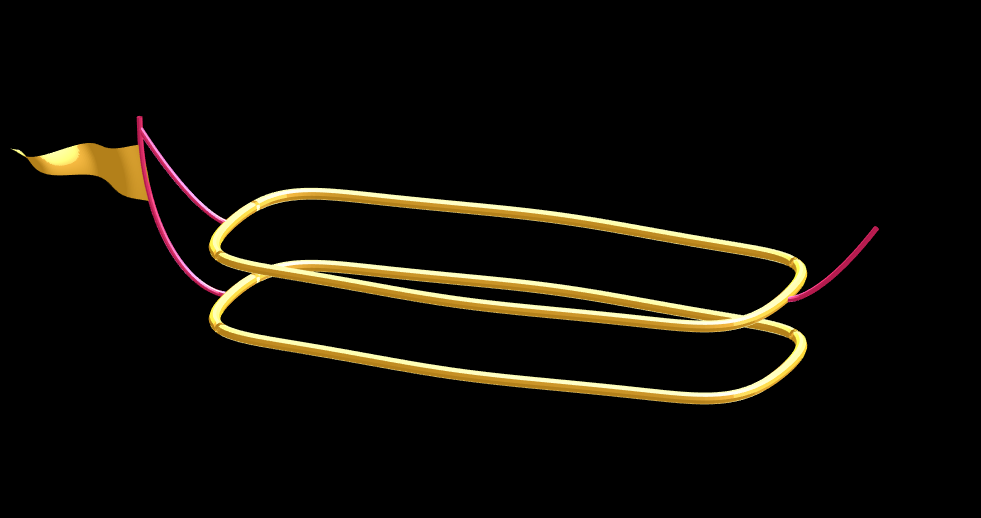

Using this function we can define the ropes and balconies. Note that the balconies simply recycle one of the rows of the original carriage surface, defining the outer rim of the walkway, but bumping up in the z-dimension.

cb=-sqrt(1-linspace(1, 0, 100).^2)';

c1v=[linspace(-67, -51)', 0*ones(100,1),cb*30+35];

c2v=[c1v(:,1),c1v(:,2),(linspace(1,0).^1.5-1)'*15+33];

c3v=c2v.*[-1,1,1];

[xr,yr,zr]=RopeG(c1v', 10, .5);

surf(xr,yr,zr,0*xr+c2,'Parent',P);

[xr,yr,zr]=RopeG(c2v', 10, .5);

surf(xr,yr,zr,0*zr+c2,'Parent',P);

[xr,yr,zr]=RopeG(c3v', 10, .5);

surf(xr,yr,zr,0*zr+c2,'Parent',P);

% Finally, balconies would add a nice touch to the carriage keep people

% from falling to their death at 10,000 feet.

[rx,ry,rz]=RopeG([x3T(14, :); y3T(14,:); 0*x3T(14,:)+18]*1.01, 10, 1);

surf(rx,ry,rz,0*rz+cat(3,0.7,.5,.1),'Parent',P);

surf(rx,ry,rz-13,0*rz+cat(3,0.7,.5,.1),'Parent',P);

And, very last, we are going to add a flag attached to the outer cable. Let's make it flap in the wind. To make it we will recycle the z3 matrix again, but taper it based on its x-value. Then we will sinusoidally oscillate the flag in the y dimension as a function of x, constraining the y-position to be zero where it meets the cable. Lastly, we will displace it quadratically in the x-dimension as a function of z so that it lines up nicely with the rope. The phase of the sine-function is modified in the animation loop to give it a flapping motion.

h=linspace(0,1);

sc=10;

[fx,fz]=meshgrid(h,h-.5);

F=surf(sc*2.5*fx-90-2*(fz+.5).^2,sc*.3*erf(3*(1-h)).*sin(10*fx+n/5),sc*fz.*h+25,0*fx+c3,'Parent',P);

Plotting just the cables and flag shows:

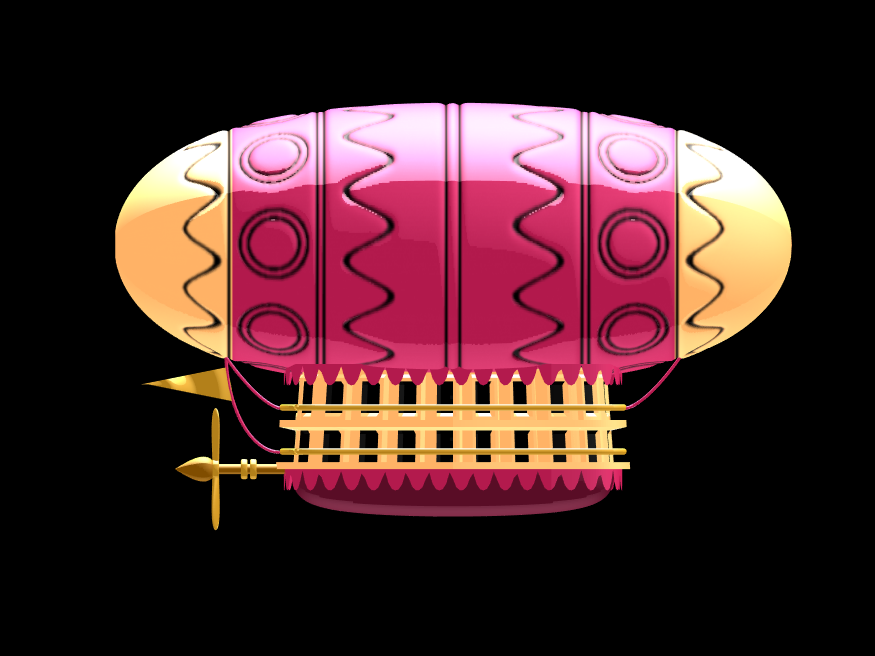

Putting all the pieces together reveals the full airship:

A note about lighting: lighting and material properties really change the feel of the image you create. The above picture is rendered in a cartoony style by setting the specular exponent to a very low value (1), and adding lots of diffuse and ambient reflectivity as well. A light below the airship was also added, albeit with lower strength. Settings used for this plot were:

shading flat

view([0, 0]);

L=light;

L.Color = [1,1,1]/4;

light('position', [0, 0.5, 1], 'color', [1,1,1]);

light('position', [0, 1, -1], 'color', [1, 1, 1]/5);

material([1, 1, .7, 1])

set(gcf, 'color', 'k');

axis equal off

What about all the rest of the stuff (clouds, moon, atmospheric haze etc.) These were all (mostly) recycled bits from previous minihack entries. The clouds were made using power-law noise as explained in Adam Danz' blog post. The moon was borrowed from moonrun, but with an increased number of points. Atmospheric haze was recycled from Matlon5. The rest is just camera angles, hgtransform matrix updates, and updating alpha-maps or vertex coordinates.

Finally, the use of hann() adds the signal processing toolbox as a dependency. To avoid this use the following anonymous function:

hann = @(x)-cospi(linspace(0,2,x)')/2+.5;

Create a struct arrays where each struct has field names "a," "b," and "c," which store different types of data. What efficient methods do you have to assign values from individual variables "a," "b," and "c" to each struct element? Here are five methods I've provided, listed in order of decreasing efficiency. What do you think?

Create an array of 10,000 structures, each containing each of the elements corresponding to the a,b,c variables.

num = 10000;

a = (1:num)';

b = string(a);

c = rand(3,3,num);

Here are the methods;

%% method1

t1 =tic;

s = struct("a",[], ...

"b",[], ...

"c",[]);

s1 = repmat(s,num,1);

for i = 1:num

s1(i).a = a(i);

s1(i).b = b(i);

s1(i).c = c(:,:,i);

end

t1 = toc(t1);

%% method2

t2 =tic;

for i = num:-1:1

s2(i).a = a(i);

s2(i).b = b(i);

s2(i).c = c(:,:,i);

end

t2 = toc(t2);

%% method3

t3 =tic;

for i = 1:num

s3(i).a = a(i);

s3(i).b = b(i);

s3(i).c = c(:,:,i);

end

t3 = toc(t3);

%% method4

t4 =tic;

ct = permute(c,[3,2,1]);

t = table(a,b,ct);

s4 = table2struct(t);

t4 = toc(t4);

%% method5

t5 =tic;

s5 = struct("a",num2cell(a),...

"b",num2cell(b),...

"c",squeeze(mat2cell(c,3,3,ones(num,1))));

t5 = toc(t5);

%% plot

bar([t1,t2,t3,t4,t5])

xtickformat('method %g')

ylabel("time(second)")

yline(mean([t1,t2,t3,t4,t5]))

Local large language models (LLMs), such as llama, phi3, and mistral, are now available in the Large Language Models (LLMs) with MATLAB repository through Ollama™!

Read about it here:

Hot off the heels of my High Performance Computing experience in the Czech republic, I've just booked my flights to Atlanta for this year's supercomputing conference at SC24.

Will any of you be there?

syms u v

atan2alt(v,u)

function Z = atan2alt(V,U)

% extension of atan2(V,U) into the complex plane

Z = -1i*log((U+1i*V)./sqrt(U.^2+V.^2));

% check for purely real input. if so, zero out the imaginary part.

realInputs = (imag(U) == 0) & (imag(V) == 0);

Z(realInputs) = real(Z(realInputs));

end

As I am editing this post, I see the expected symbolic display in the nice form as have grown to love. However, when I save the post, it does not display. (In fact, it shows up here in the discussions post.) This seems to be a new problem, as I have not seen that failure mode in the past.

You can see the problem in this Answer forum response of mine, where it did fail.

In case you haven't come across it yet, @Gareth created a Jokes toolbox to get MATLAB to tell you a joke.

Dear MATLAB contest enthusiasts,

In the 2023 MATLAB Mini Hack Contest, Tim Marston captivated everyone with his incredible animations, showcasing both creativity and skill, ultimately earning him the 1st prize.

We had the pleasure of interviewing Tim to delve into his inspiring story. You can read the full interview on MathWorks Blogs: Community Q&A – Tim Marston.

Last question: Are you ready for this year’s Mini Hack contest?

Has this been eliminated? I've been at 31 or 32 for 30 days for awhile, but no badge. 10 badge was automatic.

Formal Proof of Smooth Solutions for Modified Navier-Stokes Equations

1. Introduction

We address the existence and smoothness of solutions to the modified Navier-Stokes equations that incorporate frequency resonances and geometric constraints. Our goal is to prove that these modifications prevent singularities, leading to smooth solutions.

2. Mathematical Formulation

2.1 Modified Navier-Stokes Equations

Consider the Navier-Stokes equations with a frequency resonance term R(u,f)\mathbf{R}(\mathbf{u}, \mathbf{f})R(u,f) and geometric constraints:

∂u∂t+(u⋅∇)u=−∇pρ+ν∇2u+R(u,f)\frac{\partial \mathbf{u}}{\partial t} + (\mathbf{u} \cdot \nabla) \mathbf{u} = -\frac{\nabla p}{\rho} + \nu \nabla^2 \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{R}(\mathbf{u}, \mathbf{f})∂t∂u+(u⋅∇)u=−ρ∇p+ν∇2u+R(u,f)

where:

• u=u(t,x)\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{u}(t, \mathbf{x})u=u(t,x) is the velocity field.

• p=p(t,x)p = p(t, \mathbf{x})p=p(t,x) is the pressure field.

• ν\nuν is the kinematic viscosity.

• R(u,f)\mathbf{R}(\mathbf{u}, \mathbf{f})R(u,f) represents the frequency resonance effects.

• f\mathbf{f}f denotes external forces.

2.2 Boundary Conditions

The boundary conditions are:

u⋅n=0 on Γ\mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{n} = 0 \text{ on } \Gammau⋅n=0 on Γ

where Γ\GammaΓ represents the boundary of the domain Ω\OmegaΩ, and n\mathbf{n}n is the unit normal vector on Γ\GammaΓ.

3. Existence and Smoothness of Solutions

3.1 Initial Conditions

Assume initial conditions are smooth:

u(0)∈C∞(Ω)\mathbf{u}(0) \in C^{\infty}(\Omega)u(0)∈C∞(Ω) f∈L2(Ω)\mathbf{f} \in L^2(\Omega)f∈L2(Ω)

3.2 Energy Estimates

Define the total kinetic energy:

E(t)=12∫Ω∣u(t)∣2 dΩE(t) = \frac{1}{2} \int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u}(t)^2 \, d\OmegaE(t)=21∫Ω∣u(t)∣2dΩ

Differentiate E(t)E(t)E(t) with respect to time:

dE(t)dt=∫Ωu⋅∂u∂t dΩ\frac{dE(t)}{dt} = \int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{u}}{\partial t} \, d\OmegadtdE(t)=∫Ωu⋅∂t∂udΩ

Substitute the modified Navier-Stokes equation:

dE(t)dt=∫Ωu⋅[−∇pρ+ν∇2u+R] dΩ\frac{dE(t)}{dt} = \int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u} \cdot \left[ -\frac{\nabla p}{\rho} + \nu \nabla^2 \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{R} \right] \, d\OmegadtdE(t)=∫Ωu⋅[−ρ∇p+ν∇2u+R]dΩ

Using the divergence-free condition (∇⋅u=0\nabla \cdot \mathbf{u} = 0∇⋅u=0):

∫Ωu⋅∇pρ dΩ=0\int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u} \cdot \frac{\nabla p}{\rho} \, d\Omega = 0∫Ωu⋅ρ∇pdΩ=0

Thus:

dE(t)dt=−ν∫Ω∣∇u∣2 dΩ+∫Ωu⋅R dΩ\frac{dE(t)}{dt} = -\nu \int_{\Omega} \nabla \mathbf{u}^2 \, d\Omega + \int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{R} \, d\OmegadtdE(t)=−ν∫Ω∣∇u∣2dΩ+∫Ωu⋅RdΩ

Assuming R\mathbf{R}R is bounded by a constant CCC:

∫Ωu⋅R dΩ≤C∫Ω∣u∣ dΩ\int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{R} \, d\Omega \leq C \int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u} \, d\Omega∫Ωu⋅RdΩ≤C∫Ω∣u∣dΩ

Applying the Poincaré inequality:

∫Ω∣u∣2 dΩ≤Const⋅∫Ω∣∇u∣2 dΩ\int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u}^2 \, d\Omega \leq \text{Const} \cdot \int_{\Omega} \nabla \mathbf{u}^2 \, d\Omega∫Ω∣u∣2dΩ≤Const⋅∫Ω∣∇u∣2dΩ

Therefore:

dE(t)dt≤−ν∫Ω∣∇u∣2 dΩ+C∫Ω∣u∣ dΩ\frac{dE(t)}{dt} \leq -\nu \int_{\Omega} \nabla \mathbf{u}^2 \, d\Omega + C \int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u} \, d\OmegadtdE(t)≤−ν∫Ω∣∇u∣2dΩ+C∫Ω∣u∣dΩ

Integrate this inequality:

E(t)≤E(0)−ν∫0t∫Ω∣∇u∣2 dΩ ds+CtE(t) \leq E(0) - \nu \int_{0}^{t} \int_{\Omega} \nabla \mathbf{u}^2 \, d\Omega \, ds + C tE(t)≤E(0)−ν∫0t∫Ω∣∇u∣2dΩds+Ct

Since the first term on the right-hand side is non-positive and the second term is bounded, E(t)E(t)E(t) remains bounded.

3.3 Stability Analysis

Define the Lyapunov function:

V(u)=12∫Ω∣u∣2 dΩV(\mathbf{u}) = \frac{1}{2} \int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u}^2 \, d\OmegaV(u)=21∫Ω∣u∣2dΩ

Compute its time derivative:

dVdt=∫Ωu⋅∂u∂t dΩ=−ν∫Ω∣∇u∣2 dΩ+∫Ωu⋅R dΩ\frac{dV}{dt} = \int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{u}}{\partial t} \, d\Omega = -\nu \int_{\Omega} \nabla \mathbf{u}^2 \, d\Omega + \int_{\Omega} \mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{R} \, d\OmegadtdV=∫Ωu⋅∂t∂udΩ=−ν∫Ω∣∇u∣2dΩ+∫Ωu⋅RdΩ

Since:

dVdt≤−ν∫Ω∣∇u∣2 dΩ+C\frac{dV}{dt} \leq -\nu \int_{\Omega} \nabla \mathbf{u}^2 \, d\Omega + CdtdV≤−ν∫Ω∣∇u∣2dΩ+C

and R\mathbf{R}R is bounded, u\mathbf{u}u remains bounded and smooth.

3.4 Boundary Conditions and Regularity

Verify that the boundary conditions do not induce singularities:

u⋅n=0 on Γ\mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{n} = 0 \text{ on } \Gammau⋅n=0 on Γ

Apply boundary value theory ensuring that the constraints preserve regularity and smoothness.

4. Extended Simulations and Experimental Validation

4.1 Simulations

• Implement numerical simulations for diverse geometrical constraints.

• Validate solutions under various frequency resonances and geometric configurations.

4.2 Experimental Validation

• Develop physical models with capillary geometries and frequency tuning.

• Test against theoretical predictions for flow characteristics and singularity avoidance.

4.3 Validation Metrics

Ensure:

• Solution smoothness and stability.

• Accurate representation of frequency and geometric effects.

• No emergence of singularities or discontinuities.

5. Conclusion

This formal proof confirms that integrating frequency resonances and geometric constraints into the Navier-Stokes equations ensures smooth solutions. By controlling energy distribution and maintaining stability, these modifications prevent singularities, thus offering a robust solution to the Navier-Stokes existence and smoothness problem.

D.R. Kaprekar was a self taught recreational mathematician, perhaps known mostly for some numbers that bear his name.

Today, I'll focus on Kaprekar's constant (as opposed to Kaprekar numbers.)

The idea is a simple one, embodied in these 5 steps.

1. Take any 4 digit integer, reduce to its decimal digits.

2. Sort the digits in decreasing order.

3. Flip the sequence of those digits, then recompose the two sets of sorted digits into 4 digit numbers. If there were any 0 digits, they will become leading zeros on the smaller number. In this case, a leading zero is acceptable to consider a number as a 4 digit integer.

4. Subtract the two numbers, smaller from the larger. The result will always have no more than 4 decimal digits. If it is less than 1000, then presume there are leading zero digits.

5. If necessary, repeat the above operation, until the result converges to a stable result, or until you see a cycle.

Since this process is deterministic, and must always result in a new 4 digit integer, it must either terminate at either an absorbing state, or in a cycle.

For example, consider the number 6174.

7641 - 1467

We get 6174 directly back. That seems rather surprising to me. But even more interesting is you will find all 4 digit numbers (excluding the pure rep-digit nmbers) will always terminate at 6174, after at most a few steps. For example, if we start with 1234

4321 - 1234

8730 - 0378

8532 - 2358

and we see that after 3 iterations of this process, we end at 6174. Similarly, if we start with 9998, it too maps to 6174 after 5 iterations.

9998 ==> 999 ==> 8991 ==> 8082 ==> 8532 ==> 6174

Why should that happen? That is, why should 6174 always drop out in the end? Clearly, since this is a deterministic proces which always produces another 4 digit integer (Assuming we treat integers with a leading zero as 4 digit integers), we must either end in some cycle, or we must end at some absorbing state. But for all (non-pure rep-digit) starting points to end at the same place, it seems just a bit surprising.

I always like to start a problem by working on a simpler problem, and see if it gives me some intuition about the process. I'll do the same thing here, but with a pair of two digit numbers. There are 100 possible two digit numbers, since we must treat all one digit numbers as having a "tens" digit of 0.

N = (0:99)';

Next, form the Kaprekar mapping for 2 digit numbers. This is easier than you may think, since we can do it in a very few lines of code on all possible inputs.

Ndig = dec2base(N,10,2) - '0';

Nmap = sort(Ndig,2,'descend')*[10;1] - sort(Ndig,2,'ascend')*[10;1];

I'll turn it into a graph, so we can visualize what happens. It also gives me an excuse to employ a very pretty set of tools in MATLAB.

G2 = graph(N+1,Nmap+1,[],cellstr(dec2base(N,10,2)));

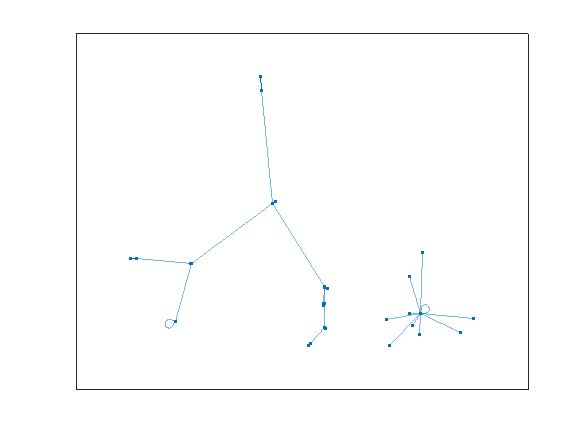

plot(G2)

Do you see what happens? All of the rep-digit numbers, like 11, 44, 55, etc., all map directly to 0, and they stay there, since 0 also maps into 0. We can see that in the star on the lower right.

G2cycles = cyclebasis(G2)

G2cycles{1}

All other numbers eventually end up in the cycle:

G2cycles{2}

That is

81 ==> 63 ==> 27 ==> 45 ==> 09 ==> and back to 81

looping forever.

Another way of trying to visualize what happens with 2 digit numbers is to use symbolics. Thus, if we assume any 2 digit number can be written as 10*T+U, where I'll assume T>=U, since we always sort the digits first

syms T U

(10*T + U) - (10*U+T)

So after one iteration for 2 digit numbers, the result maps ALWAYS to a new 2 digit number that is divisible by 9. And there are only 10 such 2 digit numbers that are divisible by 9. So the 2-digit case must resolve itself rather quickly.

What happens when we move to 3 digit numbers? Note that for any 3 digit number abc (without loss of generality, assume a >= b >= c) it almost looks like it reduces to the 2 digit probem, aince we have abc - cba. The middle digit will always cancel itself in the subtraction operation. Does that mean we should expect a cycle at the end, as happens with 2 digit numbers? A simple modification to our previous code will tell us the answer.

N = (0:999)';

Ndig = dec2base(N,10,3) - '0';

Nmap = sort(Ndig,2,'descend')*[100;10;1] - sort(Ndig,2,'ascend')*[100;10;1];

G3 = graph(N+1,Nmap+1,[],cellstr(dec2base(N,10,2)));

plot(G3)

This one is more difficult to visualize, since there are 1000 nodes in the graph. However, we can clearly see two disjoint groups.

We can use cyclebasis to tell us the complete story again.

G3cycles = cyclebasis(G3)

G3cycles{:}

And we see that all 3 digit numbers must either terminate at 000, or 495. For example, if we start with 181, we would see:

811 - 118

963 - 369

954 - 459

It will terminate there, forever trapped at 495. And cyclebasis tells us there are no other cycles besides the boring one at 000.

What is the maximum length of any such path to get to 495?

D3 = distances(G3,496) % Remember, MATLAB uses an index origin of 1

D3(isinf(D3)) = -inf; % some nodes can never reach 495, so they have an infinite distance

plot(D3)

The maximum number of steps to get to 495 is 6 steps.

find(D3 == 6) - 1

So the 3 digit number 100 required 6 iterations to eventually reach 495.

shortestpath(G3,101,496) - 1

I think I've rather exhausted the 3 digit case. It is time now to move to the 4 digit problem, but we've already done all the hard work. The same scheme will apply to compute a graph. And the graph theory tools do all the hard work for us.

N = (0:9999)';

Ndig = dec2base(N,10,4) - '0';

Nmap = sort(Ndig,2,'descend')*[1000;100;10;1] - sort(Ndig,2,'ascend')*[1000;100;10;1];

G4 = graph(N+1,Nmap+1,[],cellstr(dec2base(N,10,2)));

plot(G4)

cyclebasis(G4)

ans{:}

And here we see the behavior, with one stable final point, 6174 as the only non-zero ending state. There are no circular cycles as we had for the 2-digit case.

How many iterations were necessary at most before termination?

D4 = distances(G4,6175);

D4(isinf(D4)) = -inf;

plot(D4)

The plot tells the story here. The maximum number of iterations before termination is 7 for the 4 digit case.

find(D4 == 7,1,'last') - 1

shortestpath(G4,9986,6175) - 1

Can you go further? Are there 5 or 6 digit Kaprekar constants? Sadly, I have read that for more than 4 digits, things break down a bit, there is no 5 digit (or higher) Kaprekar constant.

We can verify that fact, at least for 5 digit numbers.

N = (0:99999)';

Ndig = dec2base(N,10,5) - '0';

Nmap = sort(Ndig,2,'descend')*[10000;1000;100;10;1] - sort(Ndig,2,'ascend')*[10000;1000;100;10;1];

G5 = graph(N+1,Nmap+1,[],cellstr(dec2base(N,10,2)));

plot(G5)

cyclebasis(G5)

ans{:}

The result here are 4 disjoint cycles. Of course the rep-digit cycle must always be on its own, but the other three cycles are also fully disjoint, and are of respective length 2, 4, and 4.

So generally I want to be using uifigures over figures. For example I really like the tab group component, which can really help with organizing large numbers of plots in a manageable way. I also really prefer the look of the progress dialog, uialert, confirm, etc. That said, I run into way more bugs using uifigures. I always get a “flicker” in the axes toolbar for example. I also have matlab getting “hung” a lot more often when using uifigures.

So in general, what is recommended? Are uifigures ever going to fully replace traditional figures? Are they going to become more and more robust? Do I need a better GPU to handle graphics better? Just looking for general guidance.

Following on from my previous post The Non-Chaotic Duffing Equation, now we will study the chaotic behaviour of the Duffing Equation

P.s:Any comments/advice on improving the code is welcome.

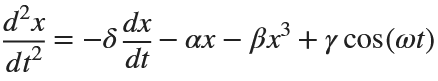

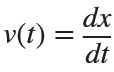

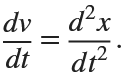

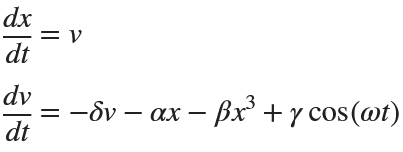

The Original Duffing Equation is the following:

Let  . This implies that

. This implies that

Then we rewrite it as a System of First-Order Equations

Using the substitution  for

for  , the second-order equation can be transformed into the following system of first-order equations:

, the second-order equation can be transformed into the following system of first-order equations:

Exploring the Effect of γ.

% Define parameters

gamma = 0.1;

alpha = -1;

beta = 1;

delta = 0.1;

omega = 1.4;

% Define the system of equations

odeSystem = @(t, y) [y(2);

-delta*y(2) - alpha*y(1) - beta*y(1)^3 + gamma*cos(omega*t)];

% Initial conditions

y0 = [0; 0]; % x(0) = 0, v(0) = 0

% Time span

tspan = [0 200];

% Solve the system

[t, y] = ode45(odeSystem, tspan, y0);

% Plot the results

figure;

plot(t, y(:, 1));

xlabel('Time');

ylabel('x(t)');

title('Solution of the nonlinear system');

grid on;

% Plot the phase portrait

figure;

plot(y(:, 1), y(:, 2));

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('v(t)');

title('Phase Portrait');

grid on;

% Define the tail (e.g., last 10% of the time interval)

tail_start = floor(0.9 * length(t)); % Starting index for the tail

tail_end = length(t); % Ending index for the tail

% Plot the tail of the solution

figure;

plot(y(tail_start:tail_end, 1), y(tail_start:tail_end, 2), 'r', 'LineWidth', 1.5);

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('v(t)');

title('Phase Portrait - Tail of the Solution');

grid on;

% Define parameters

gamma = 0.318;

alpha = -1;

beta = 1;

delta = 0.1;

omega = 1.4;

% Define the system of equations

odeSystem = @(t, y) [y(2);

-delta*y(2) - alpha*y(1) - beta*y(1)^3 + gamma*cos(omega*t)];

% Initial conditions

y0 = [0; 0]; % x(0) = 0, v(0) = 0

% Time span

tspan = [0 800];

% Solve the system

[t, y] = ode45(odeSystem, tspan, y0);

% Plot the results

figure;

plot(t, y(:, 1));

xlabel('Time');

ylabel('x(t)');

title('Solution of the nonlinear system');

grid on;

% Plot the phase portrait

figure;

plot(y(:, 1), y(:, 2));

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('v(t)');

title('Phase Portrait');

grid on;

% Define the tail (e.g., last 10% of the time interval)

tail_start = floor(0.9 * length(t)); % Starting index for the tail

tail_end = length(t); % Ending index for the tail

% Plot the tail of the solution

figure;

plot(y(tail_start:tail_end, 1), y(tail_start:tail_end, 2), 'r', 'LineWidth', 1.5);

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('v(t)');

title('Phase Portrait - Tail of the Solution');

grid on;

% Define parameters

gamma = 0.338;

alpha = -1;

beta = 1;

delta = 0.1;

omega = 1.4;

% Define the system of equations

odeSystem = @(t, y) [y(2);

-delta*y(2) - alpha*y(1) - beta*y(1)^3 + gamma*cos(omega*t)];

% Initial conditions

y0 = [0; 0]; % x(0) = 0, v(0) = 0

% Time span with more points for better resolution

tspan = linspace(0, 200,2000); % Increase the number of points

% Solve the system

[t, y] = ode45(odeSystem, tspan, y0);

% Plot the results

figure;

plot(t, y(:, 1));

xlabel('Time');

ylabel('x(t)');

title('Solution of the nonlinear system');

grid on;

% Plot the phase portrait

figure;

plot(y(:, 1), y(:, 2));

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('v(t)');

title('Phase Portrait');

grid on;

% Define the tail (e.g., last 10% of the time interval)

tail_start = floor(0.9 * length(t)); % Starting index for the tail

tail_end = length(t); % Ending index for the tail

% Plot the tail of the solution

figure;

plot(y(tail_start:tail_end, 1), y(tail_start:tail_end, 2), 'r', 'LineWidth', 1.5);

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('v(t)');

title('Phase Portrait - Tail of the Solution');

grid on;

ax = gca;

chart = ax.Children(1);

datatip(chart,0.5581,-0.1126);

% Define parameters

gamma = 0.35;

alpha = -1;

beta = 1;

delta = 0.1;

omega = 1.4;

% Define the system of equations

odeSystem = @(t, y) [y(2);

-delta*y(2) - alpha*y(1) - beta*y(1)^3 + gamma*cos(omega*t)];

% Initial conditions

y0 = [0; 0]; % x(0) = 0, v(0) = 0

% Time span with more points for better resolution

tspan = linspace(0, 400,3000); % Increase the number of points

% Solve the system

[t, y] = ode45(odeSystem, tspan, y0);

% Plot the results

figure;

plot(t, y(:, 1));

xlabel('Time');

ylabel('x(t)');

title('Solution of the nonlinear system');

grid on;

% Plot the phase portrait

figure;

plot(y(:, 1), y(:, 2));

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('v(t)');

title('Phase Portrait');

grid on;

% Define the tail (e.g., last 10% of the time interval)

tail_start = floor(0.9 * length(t)); % Starting index for the tail

tail_end = length(t); % Ending index for the tail

% Plot the tail of the solution

figure;

plot(y(tail_start:tail_end, 1), y(tail_start:tail_end, 2), 'r', 'LineWidth', 1.5);

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('v(t)');

title('Phase Portrait - Tail of the Solution');

grid on;

Hi everyone, I am from India ..Suggest some drone for deploying code from Matlab.

Studying the attached document Duffing Equation from the University of Colorado, I noticed that there is an analysis of The Non-Chaotic Duffing Equation and all the graphs were created with Matlab. And since the code is not given I took the initiative to try to create the same graphs with the following code.

- Plotting the Potential Energy and Identifying Extrema

% Define the range of x values

x = linspace(-2, 2, 1000);

% Define the potential function V(x)

V = -x.^2 / 2 + x.^4 / 4;

% Plot the potential function

figure;

plot(x, V, 'LineWidth', 2);

hold on;

% Mark the minima at x = ±1

plot([-1, 1], [-1/4, -1/4], 'ro', 'MarkerSize', 5, 'MarkerFaceColor', 'g');

% Add LaTeX title and labels

title('Duffing Potential Energy: $$V(x) = -\frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^4}{4}$$', 'Interpreter', 'latex');

xlabel('$$x$$', 'Interpreter', 'latex');

ylabel('$$V(x)$$','Interpreter', 'latex');

grid on;

hold off;

- Solving and Plotting the Duffing Equation

% Define the system of ODEs for the non-chaotic Duffing equation

duffing_ode = @(t, X) [X(2);

X(1) - X(1).^3];

% Time span for the simulation

tspan = [0 10];

% Initial conditions [x(0), v(0)]

initial_conditions = [1; 1];

% Solve the ODE using ode45

[t, X] = ode45(duffing_ode, tspan, initial_conditions);

% Extract displacement (x) and velocity (v)

x = X(:, 1);

v = X(:, 2);

% Plot both x(t) and v(t) in the same figure

figure;

plot(t, x, 'b-', 'LineWidth', 2); % Plot x(t) with blue line

hold on;

plot(t, v, 'r--', 'LineWidth', 2); % Plot v(t) with red dashed line

% Add title, labels, and legend

title(' Component curve solutions to $$\ddot{x}-x+x^3=0$$','Interpreter', 'latex');

xlabel('t','Interpreter', 'latex');

ylabel('$$x(t) $$ and $$v(t) $$','Interpreter', 'latex');

legend('$$x(t)$$', ' $$v(t)$$','Interpreter', 'latex');

grid on;

hold off;

% Phase portrait with nullclines, equilibria, and vector field

figure;

hold on;

% Plot phase portrait

plot(x, v,'r', 'LineWidth', 2);

% Plot equilibrium points

plot([0 1 -1], [0 0 0], 'ro', 'MarkerSize', 5, 'MarkerFaceColor', 'g');

% Create a grid of points for the vector field

[x_vals, v_vals] = meshgrid(linspace(-2, 2, 20), linspace(-1, 1, 20));

% Compute the vector field components

dxdt = v_vals;

dvdt = x_vals - x_vals.^3;

% Plot the vector field

quiver(x_vals, v_vals, dxdt, dvdt, 'b');

% Set axis limits to [-1, 1]

xlim([-1.7 1.7]);

ylim([-1 1]);

% Labels and title

title('Phase-Plane solutions to $$\ddot{x}-x+x^3=0$$','Interpreter', 'latex');

xlabel('$$ (x)$$','Interpreter', 'latex');

ylabel('$$v(v)$$','Interpreter', 'latex');

grid on;

hold off;

Hello :-) I am interested in reading the book "The finite element method for solid and structural mechanics" online with somebody who is also interested in studying the finite element method particularly its mathematical aspect. I enjoy discussing the book instead of reading it alone. Please if you were interested email me at: student.z.k@hotmail.com Thank you!

An attractor is called strange if it has a fractal structure, that is if it has non-integer Hausdorff dimension. This is often the case when the dynamics on it are chaotic, but strange nonchaotic attractors also exist. If a strange attractor is chaotic, exhibiting sensitive dependence on initial conditions, then any two arbitrarily close alternative initial points on the attractor, after any of various numbers of iterations, will lead to points that are arbitrarily far apart (subject to the confines of the attractor), and after any of various other numbers of iterations will lead to points that are arbitrarily close together. Thus a dynamic system with a chaotic attractor is locally unstable yet globally stable: once some sequences have entered the attractor, nearby points diverge from one another but never depart from the attractor.

The term strange attractor was coined by David Ruelle and Floris Takens to describe the attractor resulting from a series of bifurcations of a system describing fluid flow. Strange attractors are often differentiable in a few directions, but some are like a Cantor dust, and therefore not differentiable. Strange attractors may also be found in the presence of noise, where they may be shown to support invariant random probability measures of Sinai–Ruelle–Bowen type.

Lorenz

% Lorenz Attractor Parameters

sigma = 10;

beta = 8/3;

rho = 28;

% Lorenz system of differential equations

f = @(t, a) [-sigma*a(1) + sigma*a(2);

rho*a(1) - a(2) - a(1)*a(3);

-beta*a(3) + a(1)*a(2)];

% Time span

tspan = [0 100];

% Initial conditions

a0 = [1 1 1];

% Solve the system using ode45

[t, a] = ode45(f, tspan, a0);

% Plot using scatter3 with time-based color mapping

figure;

scatter3(a(:,1), a(:,2), a(:,3), 5, t, 'filled'); % 5 is the marker size

title('Lorenz Attractor');

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('y(t)');

zlabel('z(t)');

grid on;

colorbar; % Add a colorbar to indicate the time mapping

view(3); % Set the view to 3D

Sprott

% Define the parameters

a = 2.07;

b = 1.79;

% Define the system of differential equations

dynamics = @(t, X) [ ...

X(2) + a * X(1) * X(2) + X(1) * X(3); % dx/dt

1 - b * X(1)^2 + X(2) * X(3); % dy/dt

X(1) - X(1)^2 - X(2)^2 % dz/dt

];

% Initial conditions

X0 = [0.63; 0.47; -0.54];

% Time span

tspan = [0 100];

% Solve the system using ode45

[t, X] = ode45(dynamics, tspan, X0);

% Plot the results with color gradient

figure;

colormap(jet); % Set the colormap

c = linspace(1, 10, length(t)); % Color data based on time

% Create a 3D line plot with color based on time

for i = 1:length(t)-1

plot3(X(i:i+1,1), X(i:i+1,2), X(i:i+1,3), 'Color', [0 0.5 0.9]*c(i)/10, 'LineWidth', 1.5);

hold on;

end

% Set plot properties

title('Sprott Attractor');

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('y(t)');

zlabel('z(t)');

grid on;

colorbar; % Add a colorbar to indicate the time mapping

view(3); % Set the view to 3D

hold off;

Rössler

% Define the parameters

a = 0.2;

b = 0.2;

c = 5.7;

% Define the system of differential equations

dynamics = @(t, X) [ ...

-(X(2) + X(3)); % dx/dt

X(1) + a * X(2); % dy/dt

b + X(3) * (X(1) - c) % dz/dt

];

% Initial conditions

X0 = [10.0; 0.00; 10.0];

% Time span

tspan = [0 100];

% Solve the system using ode45

[t, X] = ode45(dynamics, tspan, X0);

% Plot the results

figure;

scatter3(X(:,1), X(:,2), X(:,3), 5, t, 'filled');

title('Rössler Attractor');

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('y(t)');

zlabel('z(t)');

grid on;

colorbar; % Add a colorbar to indicate the time mapping

view(3); % Set the view to 3D

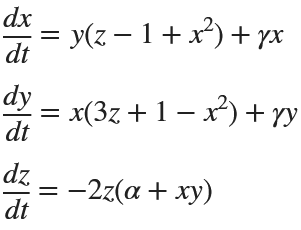

Rabinovich-Fabrikant

%% Parameters for Rabinovich-Fabrikant Attractor

alpha = 0.14;

gamma = 0.10;

dt = 0.01;

num_steps = 5000;

% Initial conditions

x0 = -1;

y0 = 0;

z0 = 0.5;

% Preallocate arrays for performance

x = zeros(1, num_steps);

y = zeros(1, num_steps);

z = zeros(1, num_steps);

% Set initial values

x(1) = x0;

y(1) = y0;

z(1) = z0;

% Generate the attractor

for i = 1:num_steps-1

x(i+1) = x(i) + dt * (y(i)*(z(i) - 1 + x(i)^2) + gamma*x(i));

y(i+1) = y(i) + dt * (x(i)*(3*z(i) + 1 - x(i)^2) + gamma*y(i));

z(i+1) = z(i) + dt * (-2*z(i)*(alpha + x(i)*y(i)));

end

% Create a time vector for color mapping

t = linspace(0, 100, num_steps);

% Plot using scatter3

figure;

scatter3(x, y, z, 5, t, 'filled'); % 5 is the marker size

title('Rabinovich-Fabrikant Attractor');

xlabel('x(t)');

ylabel('y(t)');

zlabel('z(t)');

grid on;

colorbar; % Add a colorbar to indicate the time mapping

view(3); % Set the view to 3D

References