Contenuto principale

Risultati per

Hi, I'm looking for sites where I can find coding & algorithms problems and their solutions. I'm doing this workshop in college and I'll need some problems to go over with the students and explain how Matlab works by solving the problems with them and then reviewing and going over different solution options. Does anyone know a website like that? I've tried looking in the Matlab Cody By Mathworks, but didn't exactly find what I'm looking for. Thanks in advance.

We are modeling the introduction of a novel pathogen into a completely susceptible population. In the cells below, I have provided you with the Matlab code for a simple stochastic SIR model, implemented using the "GillespieSSA" function

Simulating the stochastic model 100 times for

Since γ is 0.4 per day,  per day

per day

% Define the parameters

beta = 0.36;

gamma = 0.4;

n_sims = 100;

tf = 100; % Time frame changed to 100

% Calculate R0

R0 = beta / gamma

% Initial state values

initial_state_values = [1000000; 1; 0; 0]; % S, I, R, cum_inc

% Define the propensities and state change matrix

a = @(state) [beta * state(1) * state(2) / 1000000, gamma * state(2)];

nu = [-1, 0; 1, -1; 0, 1; 0, 0];

% Define the Gillespie algorithm function

function [t_values, state_values] = gillespie_ssa(initial_state, a, nu, tf)

t = 0;

state = initial_state(:); % Ensure state is a column vector

t_values = t;

state_values = state';

while t < tf

rates = a(state);

rate_sum = sum(rates);

if rate_sum == 0

break;

end

tau = -log(rand) / rate_sum;

t = t + tau;

r = rand * rate_sum;

cum_sum_rates = cumsum(rates);

reaction_index = find(cum_sum_rates >= r, 1);

state = state + nu(:, reaction_index);

% Update cumulative incidence if infection occurred

if reaction_index == 1

state(4) = state(4) + 1; % Increment cumulative incidence

end

t_values = [t_values; t];

state_values = [state_values; state'];

end

end

% Function to simulate the stochastic model multiple times and plot results

function simulate_stoch_model(beta, gamma, n_sims, tf, initial_state_values, R0, plot_type)

% Define the propensities and state change matrix

a = @(state) [beta * state(1) * state(2) / 1000000, gamma * state(2)];

nu = [-1, 0; 1, -1; 0, 1; 0, 0];

% Set random seed for reproducibility

rng(11);

% Initialize plot

figure;

hold on;

for i = 1:n_sims

[t, output] = gillespie_ssa(initial_state_values, a, nu, tf);

% Check if the simulation had only one step and re-run if necessary

while length(t) == 1

[t, output] = gillespie_ssa(initial_state_values, a, nu, tf);

end

if strcmp(plot_type, 'cumulative_incidence')

plot(t, output(:, 4), 'LineWidth', 2, 'Color', rand(1, 3));

elseif strcmp(plot_type, 'prevalence')

plot(t, output(:, 2), 'LineWidth', 2, 'Color', rand(1, 3));

end

end

xlabel('Time (days)');

if strcmp(plot_type, 'cumulative_incidence')

ylabel('Cumulative Incidence');

ylim([0 inf]);

elseif strcmp(plot_type, 'prevalence')

ylabel('Prevalence of Infection');

ylim([0 50]);

end

title(['Stochastic model output for R0 = ', num2str(R0)]);

subtitle([num2str(n_sims), ' simulations']);

xlim([0 tf]);

grid on;

hold off;

end

% Simulate the model 100 times and plot cumulative incidence

simulate_stoch_model(beta, gamma, n_sims, tf, initial_state_values, R0, 'cumulative_incidence');

% Simulate the model 100 times and plot prevalence

simulate_stoch_model(beta, gamma, n_sims, tf, initial_state_values, R0, 'prevalence');

Base case:

Suppose you need to do a computation many times. We are going to assume that this computation cannot be vectorized. The simplest case is to use a for loop:

number_of_elements = 1e6;

test_fcn = @(x) sqrt(x) / x;

tic

for i = 1:number_of_elements

x(i) = test_fcn(i);

end

t_forward = toc;

disp(t_forward + " seconds")

Preallocation:

This can easily be sped up by preallocating the variable that houses results:

tic

x = zeros(number_of_elements, 1);

for i = 1:number_of_elements

x(i) = test_fcn(i);

end

t_forward_prealloc = toc;

disp(t_forward_prealloc + " seconds")

In this example, preallocation speeds up the loop by a factor of about three to four (running in R2024a). Comment below if you get dramatically different results.

disp(sprintf("%.1f", t_forward / t_forward_prealloc))

Run it in reverse:

Is there a way to skip the explicit preallocation and still be fast? Indeed, there is.

clear x

tic

for i = number_of_elements:-1:1

x(i) = test_fcn(i);

end

t_backward = toc;

disp(t_backward + " seconds")

By running the loop backwards, the preallocation is implicitly performed during the first iteration and the loop runs in about the same time (within statistical noise):

disp(sprintf("%.2f", t_forward_prealloc / t_backward))

Do you get similar results when running this code? Let us know your thoughts in the comments below.

Beneficial side effect:

Have you ever had to use a for loop to delete elements from a vector? If so, keeping track of index offsets can be tricky, as deleting any element shifts all those that come after. By running the for loop in reverse, you don't need to worry about index offsets while deleting elements.

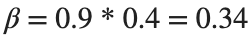

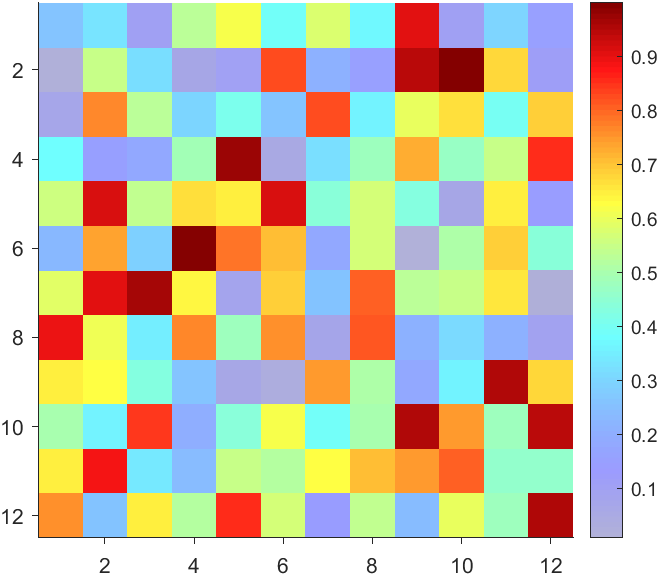

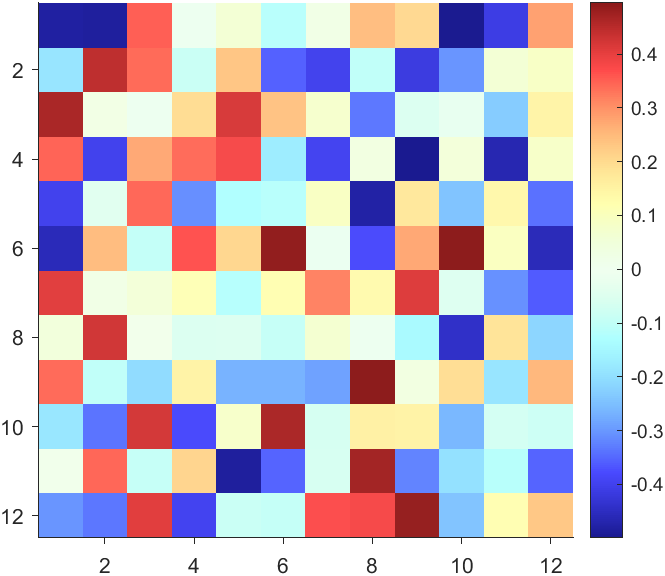

Many times when ploting, we not only need to set the color of the plot, but also its

transparency, Then how we set the alphaData of colorbar at the same time ?

It seems easy to do so :

data = rand(12,12);

% Transparency range 0-1, .3-1 for better appearance here

AData = rescale(- data, .3, 1);

% Draw an imagesc with numerical control over colormap and transparency

imagesc(data, 'AlphaData',AData);

colormap(jet);

ax = gca;

ax.DataAspectRatio = [1,1,1];

ax.TickDir = 'out';

ax.Box = 'off';

% get colorbar object

CBarHdl = colorbar;

pause(1e-16)

% Modify the transparency of the colorbar

CData = CBarHdl.Face.Texture.CData;

ALim = [min(min(AData)), max(max(AData))];

CData(4,:) = uint8(255.*rescale(1:size(CData, 2), ALim(1), ALim(2)));

CBarHdl.Face.Texture.ColorType = 'TrueColorAlpha';

CBarHdl.Face.Texture.CData = CData;

But !!!!!!!!!!!!!!! We cannot preserve the changes when saving them as images :

It seems that when saving plots, the `Texture` will be refresh, but the `Face` will not :

however, object Face only have 4 colors to change(The four corners of a quadrilateral), how

can we set more colors ??

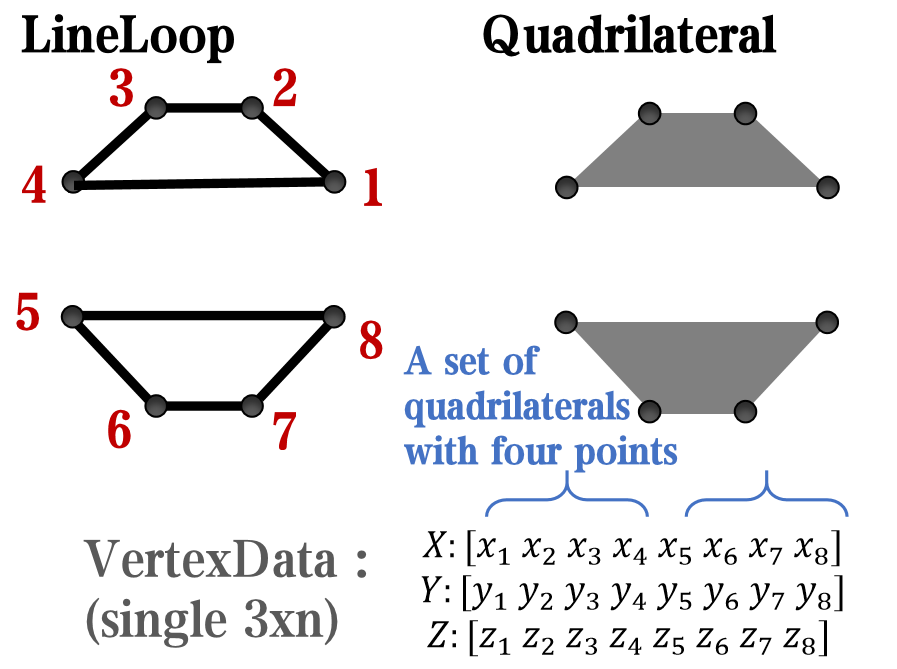

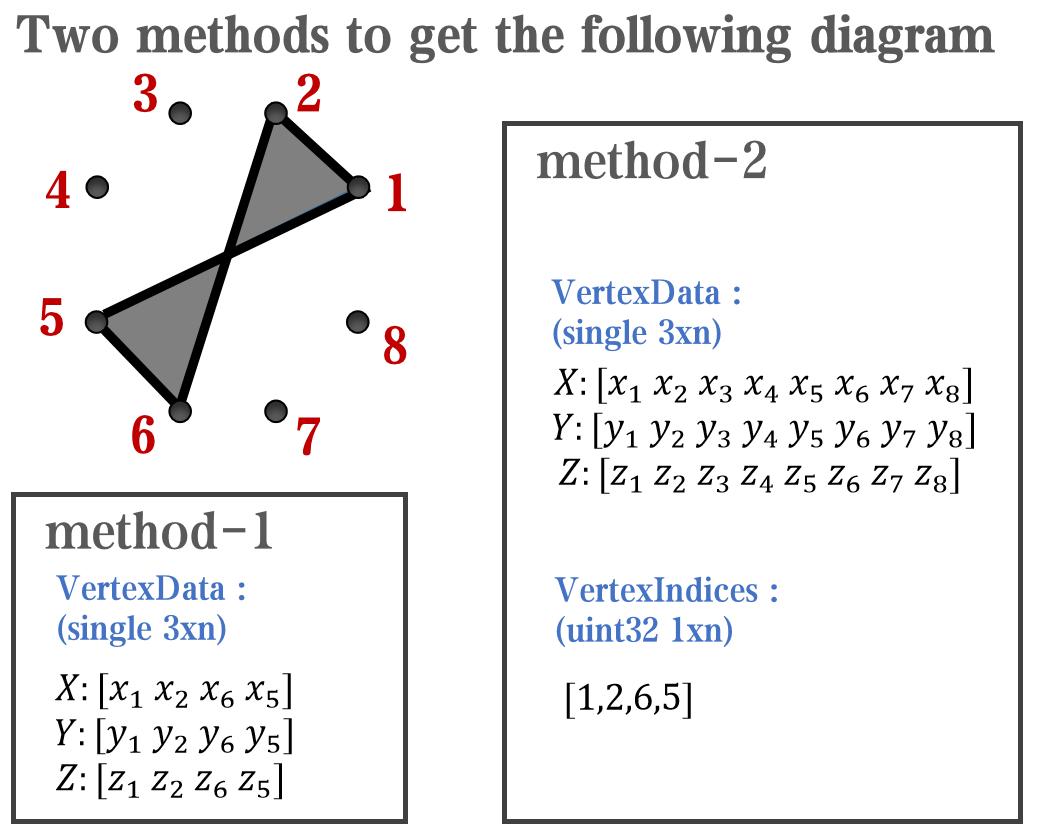

`Face` is a quadrilateral object, and we can change the `VertexData` to draw more than one little quadrilaterals:

data = rand(12,12);

% Transparency range 0-1, .3-1 for better appearance here

AData = rescale(- data, .3, 1);

%Draw an imagesc with numerical control over colormap and transparency

imagesc(data, 'AlphaData',AData);

colormap(jet);

ax = gca;

ax.DataAspectRatio = [1,1,1];

ax.TickDir = 'out';

ax.Box = 'off';

% get colorbar object

CBarHdl = colorbar;

pause(1e-16)

% Modify the transparency of the colorbar

CData = CBarHdl.Face.Texture.CData;

ALim = [min(min(AData)), max(max(AData))];

CData(4,:) = uint8(255.*rescale(1:size(CData, 2), ALim(1), ALim(2)));

warning off

CBarHdl.Face.ColorType = 'TrueColorAlpha';

VertexData = CBarHdl.Face.VertexData;

tY = repmat((1:size(CData,2))./size(CData,2), [4,1]);

tY1 = tY(:).'; tY2 = tY - tY(1,1); tY2(3:4,:) = 0; tY2 = tY2(:).';

tM1 = [tY1.*0 + 1; tY1; tY1.*0 + 1];

tM2 = [tY1.*0; tY2; tY1.*0];

CBarHdl.Face.VertexData = repmat(VertexData, [1,size(CData,2)]).*tM1 + tM2;

CBarHdl.Face.ColorData = reshape(repmat(CData, [4,1]), 4, []);

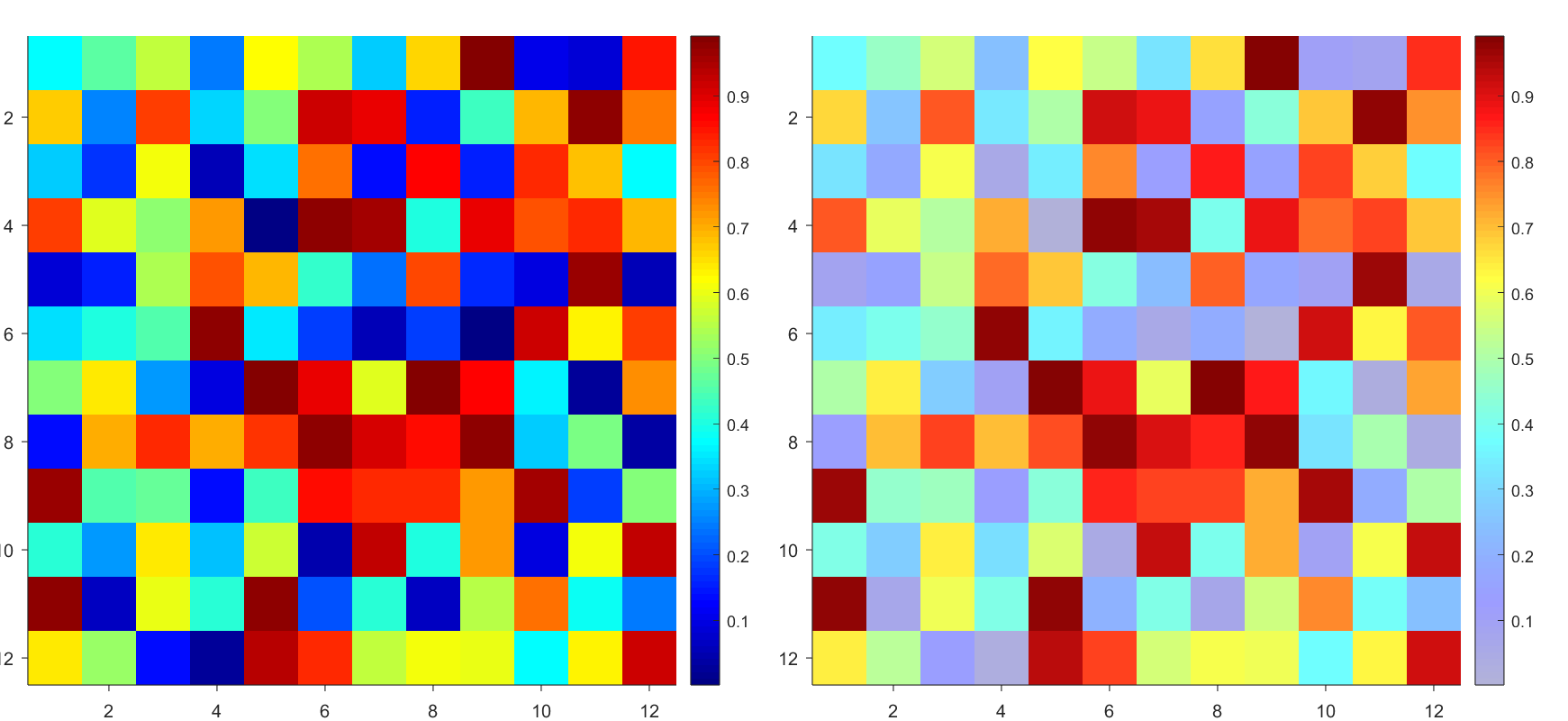

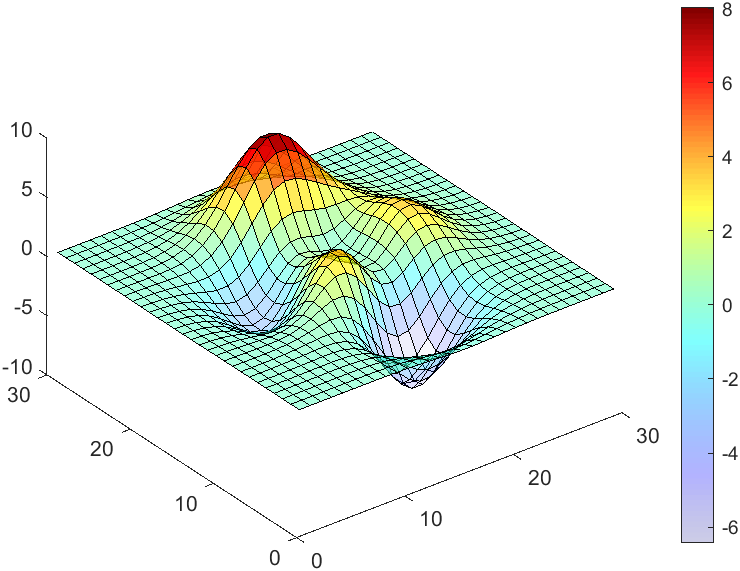

The higher the value, the more transparent it becomes

data = rand(12,12);

AData = rescale(- data, .3, 1);

imagesc(data, 'AlphaData',AData);

colormap(jet);

ax = gca;

ax.DataAspectRatio = [1,1,1];

ax.TickDir = 'out';

ax.Box = 'off';

CBarHdl = colorbar;

pause(1e-16)

CData = CBarHdl.Face.Texture.CData;

ALim = [min(min(AData)), max(max(AData))];

CData(4,:) = uint8(255.*rescale(size(CData, 2):-1:1, ALim(1), ALim(2)));

warning off

CBarHdl.Face.ColorType = 'TrueColorAlpha';

VertexData = CBarHdl.Face.VertexData;

tY = repmat((1:size(CData,2))./size(CData,2), [4,1]);

tY1 = tY(:).'; tY2 = tY - tY(1,1); tY2(3:4,:) = 0; tY2 = tY2(:).';

tM1 = [tY1.*0 + 1; tY1; tY1.*0 + 1];

tM2 = [tY1.*0; tY2; tY1.*0];

CBarHdl.Face.VertexData = repmat(VertexData, [1,size(CData,2)]).*tM1 + tM2;

CBarHdl.Face.ColorData = reshape(repmat(CData, [4,1]), 4, []);

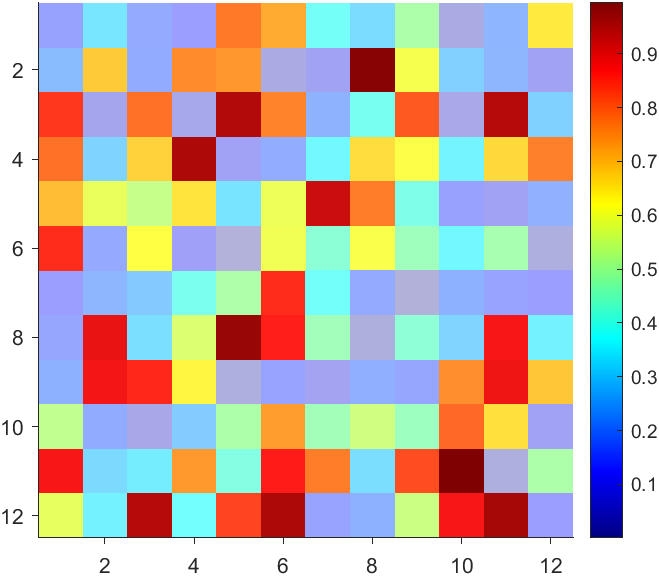

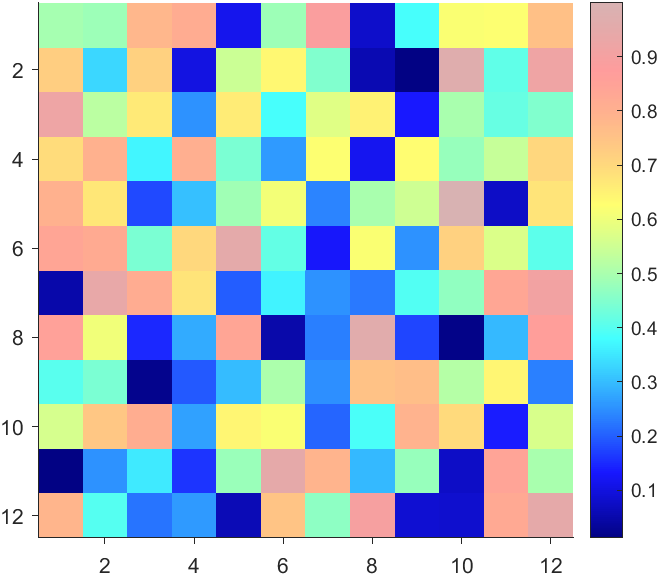

More transparent in the middle

data = rand(12,12) - .5;

AData = rescale(abs(data), .1, .9);

imagesc(data, 'AlphaData',AData);

colormap(jet);

ax = gca;

ax.DataAspectRatio = [1,1,1];

ax.TickDir = 'out';

ax.Box = 'off';

CBarHdl = colorbar;

pause(1e-16)

CData = CBarHdl.Face.Texture.CData;

ALim = [min(min(AData)), max(max(AData))];

CData(4,:) = uint8(255.*rescale(abs((1:size(CData, 2)) - (1 + size(CData, 2))/2), ALim(1), ALim(2)));

warning off

CBarHdl.Face.ColorType = 'TrueColorAlpha';

VertexData = CBarHdl.Face.VertexData;

tY = repmat((1:size(CData,2))./size(CData,2), [4,1]);

tY1 = tY(:).'; tY2 = tY - tY(1,1); tY2(3:4,:) = 0; tY2 = tY2(:).';

tM1 = [tY1.*0 + 1; tY1; tY1.*0 + 1];

tM2 = [tY1.*0; tY2; tY1.*0];

CBarHdl.Face.VertexData = repmat(VertexData, [1,size(CData,2)]).*tM1 + tM2;

CBarHdl.Face.ColorData = reshape(repmat(CData, [4,1]), 4, []);

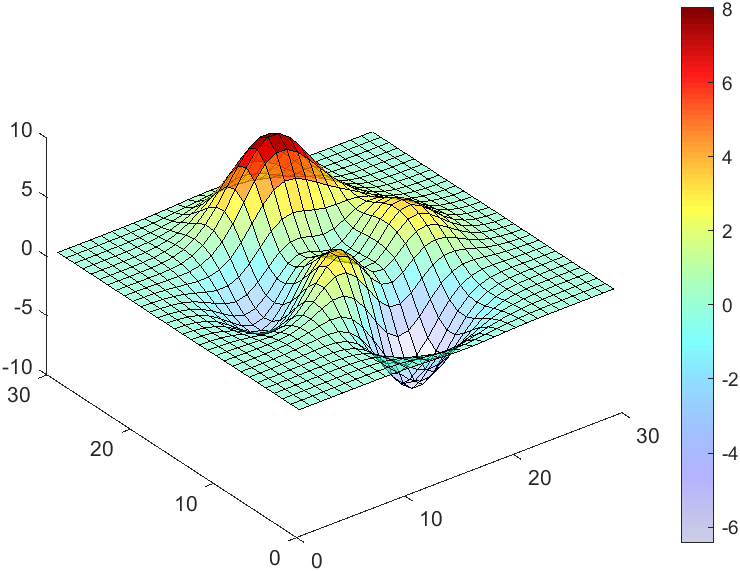

The code will work if the plot have AlphaData property

data = peaks(30);

AData = rescale(data, .2, 1);

surface(data, 'FaceAlpha','flat','AlphaData',AData);

colormap(jet(100));

ax = gca;

ax.DataAspectRatio = [1,1,1];

ax.TickDir = 'out';

ax.Box = 'off';

view(3)

CBarHdl = colorbar;

pause(1e-16)

CData = CBarHdl.Face.Texture.CData;

ALim = [min(min(AData)), max(max(AData))];

CData(4,:) = uint8(255.*rescale(1:size(CData, 2), ALim(1), ALim(2)));

warning off

CBarHdl.Face.ColorType = 'TrueColorAlpha';

VertexData = CBarHdl.Face.VertexData;

tY = repmat((1:size(CData,2))./size(CData,2), [4,1]);

tY1 = tY(:).'; tY2 = tY - tY(1,1); tY2(3:4,:) = 0; tY2 = tY2(:).';

tM1 = [tY1.*0 + 1; tY1; tY1.*0 + 1];

tM2 = [tY1.*0; tY2; tY1.*0];

CBarHdl.Face.VertexData = repmat(VertexData, [1,size(CData,2)]).*tM1 + tM2;

CBarHdl.Face.ColorData = reshape(repmat(CData, [4,1]), 4, []);

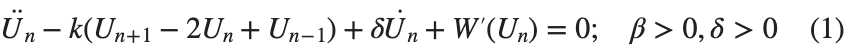

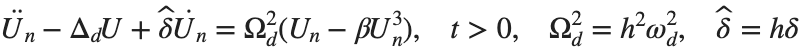

The study of the dynamics of the discrete Klein - Gordon equation (DKG) with friction is given by the equation :

In the above equation, W describes the potential function:

to which every coupled unit  adheres. In Eq. (1), the variable $

adheres. In Eq. (1), the variable $ $ is the unknown displacement of the oscillator occupying the n-th position of the lattice, and

$ is the unknown displacement of the oscillator occupying the n-th position of the lattice, and  is the discretization parameter. We denote by h the distance between the oscillators of the lattice. The chain (DKG) contains linear damping with a damping coefficient

is the discretization parameter. We denote by h the distance between the oscillators of the lattice. The chain (DKG) contains linear damping with a damping coefficient  , while

, while is the coefficient of the nonlinear cubic term.

is the coefficient of the nonlinear cubic term.

$ is the unknown displacement of the oscillator occupying the n-th position of the lattice, and

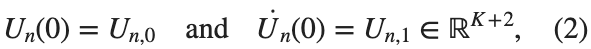

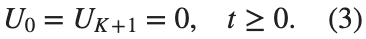

$ is the unknown displacement of the oscillator occupying the n-th position of the lattice, and For the DKG chain (1), we will consider the problem of initial-boundary values, with initial conditions

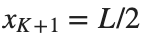

and Dirichlet boundary conditions at the boundary points  and

and  , that is,

, that is,

and

and  , that is,

, that is,

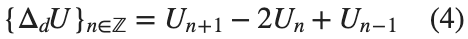

Therefore, when necessary, we will use the short notation  for the one-dimensional discrete Laplacian

for the one-dimensional discrete Laplacian

for the one-dimensional discrete Laplacian

for the one-dimensional discrete Laplacian

Now we want to investigate numerically the dynamics of the system (1)-(2)-(3). Our first aim is to conduct a numerical study of the property of Dynamic Stability of the system, which directly depends on the existence and linear stability of the branches of equilibrium points.

For the discussion of numerical results, it is also important to emphasize the role of the parameter  . By changing the time variable

. By changing the time variable  , we rewrite Eq. (1) in the form

, we rewrite Eq. (1) in the form

. We consider spatially extended initial conditions of the form:

. We consider spatially extended initial conditions of the form:We also assume zero initial velocity:

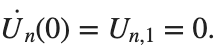

the following graphs for  and

and

% Parameters

L = 200; % Length of the system

K = 99; % Number of spatial points

j = 2; % Mode number

omega_d = 1; % Characteristic frequency

beta = 1; % Nonlinearity parameter

delta = 0.05; % Damping coefficient

% Spatial grid

h = L / (K + 1);

n = linspace(-L/2, L/2, K+2); % Spatial points

N = length(n);

omegaDScaled = h * omega_d;

deltaScaled = h * delta;

% Time parameters

dt = 1; % Time step

tmax = 3000; % Maximum time

tspan = 0:dt:tmax; % Time vector

% Values of amplitude 'a' to iterate over

a_values = [2, 1.95, 1.9, 1.85, 1.82]; % Modify this array as needed

% Differential equation solver function

function dYdt = odefun(~, Y, N, h, omegaDScaled, deltaScaled, beta)

U = Y(1:N);

Udot = Y(N+1:end);

Uddot = zeros(size(U));

% Laplacian (discrete second derivative)

for k = 2:N-1

Uddot(k) = (U(k+1) - 2 * U(k) + U(k-1)) ;

end

% System of equations

dUdt = Udot;

dUdotdt = Uddot - deltaScaled * Udot + omegaDScaled^2 * (U - beta * U.^3);

% Pack derivatives

dYdt = [dUdt; dUdotdt];

end

% Create a figure for subplots

figure;

% Initial plot

a_init = 2; % Example initial amplitude for the initial condition plot

U0_init = a_init * sin((j * pi * h * n) / L); % Initial displacement

U0_init(1) = 0; % Boundary condition at n = 0

U0_init(end) = 0; % Boundary condition at n = K+1

subplot(3, 2, 1);

plot(n, U0_init, 'r.-', 'LineWidth', 1.5, 'MarkerSize', 10); % Line and marker plot

xlabel('$x_n$', 'Interpreter', 'latex');

ylabel('$U_n$', 'Interpreter', 'latex');

title('$t=0$', 'Interpreter', 'latex');

set(gca, 'FontSize', 12, 'FontName', 'Times');

xlim([-L/2 L/2]);

ylim([-3 3]);

grid on;

% Loop through each value of 'a' and generate the plot

for i = 1:length(a_values)

a = a_values(i);

% Initial conditions

U0 = a * sin((j * pi * h * n) / L); % Initial displacement

U0(1) = 0; % Boundary condition at n = 0

U0(end) = 0; % Boundary condition at n = K+1

Udot0 = zeros(size(U0)); % Initial velocity

% Pack initial conditions

Y0 = [U0, Udot0];

% Solve ODE

opts = odeset('RelTol', 1e-5, 'AbsTol', 1e-6);

[t, Y] = ode45(@(t, Y) odefun(t, Y, N, h, omegaDScaled, deltaScaled, beta), tspan, Y0, opts);

% Extract solutions

U = Y(:, 1:N);

Udot = Y(:, N+1:end);

% Plot final displacement profile

subplot(3, 2, i+1);

plot(n, U(end,:), 'b.-', 'LineWidth', 1.5, 'MarkerSize', 10); % Line and marker plot

xlabel('$x_n$', 'Interpreter', 'latex');

ylabel('$U_n$', 'Interpreter', 'latex');

title(['$t=3000$, $a=', num2str(a), '$'], 'Interpreter', 'latex');

set(gca, 'FontSize', 12, 'FontName', 'Times');

xlim([-L/2 L/2]);

ylim([-2 2]);

grid on;

end

% Adjust layout

set(gcf, 'Position', [100, 100, 1200, 900]); % Adjust figure size as needed

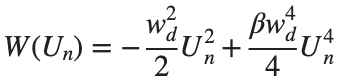

Dynamics for the initial condition ,  , for

, for  , for different amplitude values. By reducing the amplitude values, we observe the convergence to equilibrium points of different branches from

, for different amplitude values. By reducing the amplitude values, we observe the convergence to equilibrium points of different branches from  and the appearance of values

and the appearance of values  for which the solution converges to a non-linear equilibrium point

for which the solution converges to a non-linear equilibrium point  Parameters:

Parameters:

Detection of a stability threshold  : For

: For  , the initial condition ,

, the initial condition ,  , converges to a non-linear equilibrium point

, converges to a non-linear equilibrium point .

.

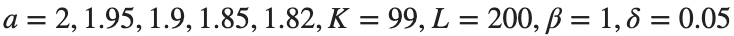

Characteristics for  , with corresponding norm

, with corresponding norm  where the dynamics appear in the first image of the third row, we observe convergence to a non-linear equilibrium point of branch

where the dynamics appear in the first image of the third row, we observe convergence to a non-linear equilibrium point of branch  This has the same norm and the same energy as the previous case but the final state has a completely different profile. This result suggests secondary bifurcations have occurred in branch

This has the same norm and the same energy as the previous case but the final state has a completely different profile. This result suggests secondary bifurcations have occurred in branch

where the dynamics appear in the first image of the third row, we observe convergence to a non-linear equilibrium point of branch

where the dynamics appear in the first image of the third row, we observe convergence to a non-linear equilibrium point of branch By further reducing the amplitude, distinct values of  are discerned: 1.9, 1.85, 1.81 for which the initial condition

are discerned: 1.9, 1.85, 1.81 for which the initial condition  with norms

with norms  respectively, converges to a non-linear equilibrium point of branch

respectively, converges to a non-linear equilibrium point of branch  This equilibrium point has norm

This equilibrium point has norm  and energy

and energy  . The behavior of this equilibrium is illustrated in the third row and in the first image of the third row of Figure 1, and also in the first image of the third row of Figure 2. For all the values between the aforementioned a, the initial condition

. The behavior of this equilibrium is illustrated in the third row and in the first image of the third row of Figure 1, and also in the first image of the third row of Figure 2. For all the values between the aforementioned a, the initial condition  converges to geometrically different non-linear states of branch

converges to geometrically different non-linear states of branch  as shown in the second image of the first row and the first image of the second row of Figure 2, for amplitudes

as shown in the second image of the first row and the first image of the second row of Figure 2, for amplitudes  and

and  respectively.

respectively.

respectively, converges to a non-linear equilibrium point of branch

respectively, converges to a non-linear equilibrium point of branch  and energy

and energy Refference:

Check out this episode about PIVLab: https://www.buzzsprout.com/2107763/15106425

Join the conversation with William Thielicke, the developer of PIVlab, as he shares insights into the world of particle image velocimetery (PIV) and its applications. Discover how PIV accurately measures fluid velocities, non invasively revolutionising research across the industries. Delve into the development journey of PI lab, including collaborations, key features and future advancements for aerodynamic studies, explore the advanced hardware setups camera technologies, and educational prospects offered by PIVlab, for enhanced fluid velocity measurements. If you are interested in the hardware he speaks of check out the company: Optolution.

How to leave feedback on a doc page

Leaving feedback is a two-step process. At the bottom of most pages in the MATLAB documentation is a star rating.

Start by selecting a star that best answers the question. After selecting a star rating, an edit box appears where you can offer specific feedback.

When you press "Submit" you'll see the confirmation dialog below. You cannot go back and edit your content, although you can refresh the page to go through that process again.

Tips on leaving feedback

- Be productive. The reader should clearly understand what action you'd like to see, what was unclear, what you think needs work, or what areas were really helpful.

- Positive feedback is also helpful. By nature, feedback often focuses on suggestions for changes but it also helps to know what was clear and what worked well.

- Point to specific areas of the page. This helps the reader to narrow the focus of the page to the area described by your feedback.

What happens to that feedback?

Before working at MathWorks I often left feedback on documentation pages but I never knew what happens after that. One day in 2021 I shared my speculation on the process:

> That feedback is received by MathWorks Gnomes which are never seen nor heard but visit the MathWorks documentation team at night while they are sleeping and whisper selected suggestions into their ears to manipulate their dreams. Occassionally this causes them to wake up with a Eureka moment that leads to changes in the documentation.

I'd like to let you in on the secret which is much less fanciful. Feedback left in the star rating and edit box are collected and periodically reviewed by the doc writers who look for trends on highly trafficked pages and finer grain feedback on less visited pages. Your feedback is important and often results in improvements.

Let's talk about probability theory in Matlab.

Conditions of the problem - how many more letters do I need to write to the sales department to get an answer?

To get closer to the problem, I need to buy a license under a contract. Maybe sometimes there are responsible employees sitting here who will give me an answer.

Thank you

In the MATLAB description of the algorithm for Lyapunov exponents, I believe there is ambiguity and misuse.

The lambda(i) in the reference literature signifies the Lyapunov exponent of the entire phase space data after expanding by i time steps, but in the calculation formula provided in the MATLAB help documentation, Y_(i+K) represents the data point at the i-th point in the reconstructed data Y after K steps, and this calculation formula also does not match the calculation code given by MATLAB. I believe there should be some misguidance and misunderstanding here.

According to the symbol regulations in the algorithm description and the MATLAB code, I think the correct formula might be y(i) = 1/dt * 1/N * sum_j( log( ||Y_(j+i) - Y_(j*+i)|| ) )

A colleague said that you can search the Help Center using the phrase 'Introduced in' followed by a release version. Such as, 'Introduced in R2022a'. Doing this yeilds search results specific for that release.

Seems pretty handy so I thought I'd share.

Are you local to Boston?

Shape the Future of MATLAB: Join MathWorks' UX Night In-Person!

When: June 25th, 6 to 8 PM

Where: MathWorks Campus in Natick, MA

🌟 Calling All MATLAB Users! Here's your unique chance to influence the next wave of innovations in MATLAB and engineering software. MathWorks invites you to participate in our special after-hours usability studies. Dive deep into the latest MATLAB features, share your valuable feedback, and help us refine our solutions to better meet your needs.

🚀 This Opportunity Is Not to Be Missed:

- Exclusive Hands-On Experience: Be among the first to explore new MATLAB features and capabilities.

- Voice Your Expertise: Share your insights and suggestions directly with MathWorks developers.

- Learn, Discover, and Grow: Expand your MATLAB knowledge and skills through firsthand experience with unreleased features.

- Network Over Dinner: Enjoy a complimentary dinner with fellow MATLAB enthusiasts and the MathWorks team. It's a perfect opportunity to connect, share experiences, and network after work.

- Earn Rewards: Participants will not only contribute to the advancement of MATLAB but will also be compensated for their time. Plus, enjoy special MathWorks swag as a token of our appreciation!

👉 Reserve Your Spot Now: Space is limited for these after-hours sessions. If you're passionate about MATLAB and eager to contribute to its development, we'd love to hear from you.

Bringing the beauty of MathWorks Natick's tulips to life through code!

Remix challenge: create and share with us your new breeds of MATLAB tulips!

Are you a Simulink user eager to learn how to create apps with App Designer? Or an App Designer enthusiast looking to dive into Simulink?

Don't miss today's article on the Graphics and App Building Blog by @Robert Philbrick! Discover how to build Simulink Apps with App Designer, streamlining control of your simulations!

Northern lights captured from this weekend at MathWorks campus ✨

Did you get a chance to see lights and take some photos?

From Alpha Vantage's website: API Documentation | Alpha Vantage

Try using the built-in Matlab function webread(URL)... for example:

% copy a URL from the examples on the site

URL = 'https://www.alphavantage.co/query?function=TIME_SERIES_DAILY&symbol=IBM&apikey=demo'

% or use the pattern to create one

tickers = [{'IBM'} {'SPY'} {'DJI'} {'QQQ'}]; i = 1;

URL = ...

['https://www.alphavantage.co/query?function=TIME_SERIES_DAILY_ADJUSTED&outputsize=full&symbol=', ...

+ tickers{i}, ...

+ '&apikey=***Put Your API Key here***'];

X = webread(URL);

You can access any of the data available on the site as per the Alpha Vantage documentation using these two lines of code but with different designations for the requested data as per the documentation.

It's fun!

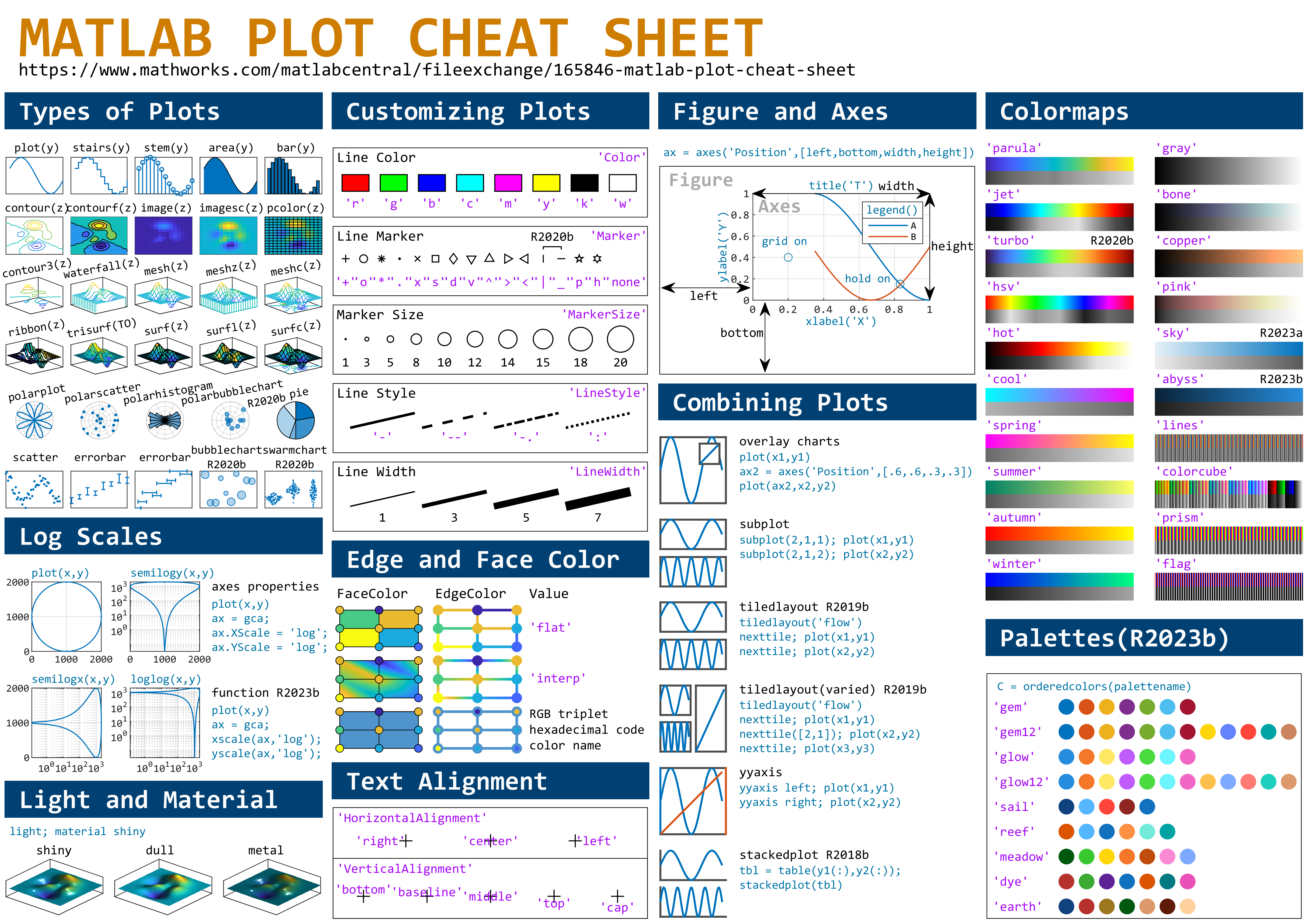

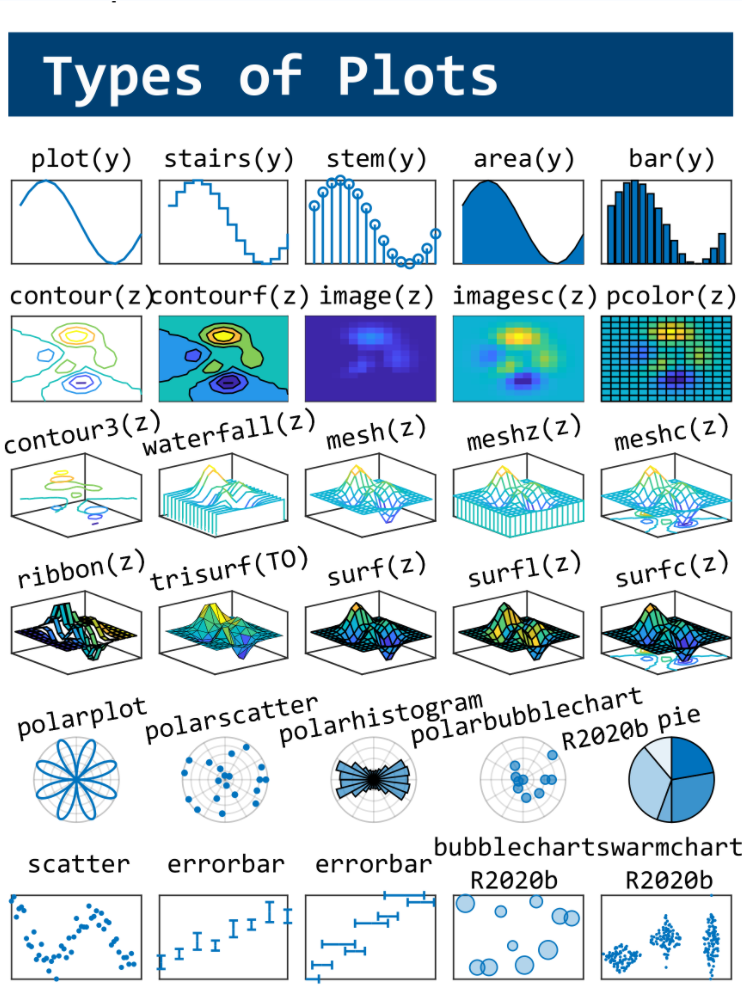

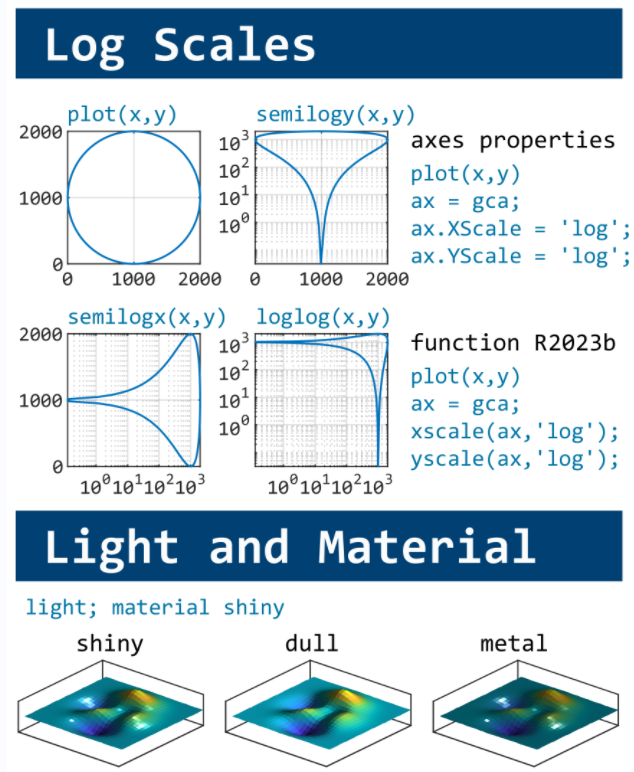

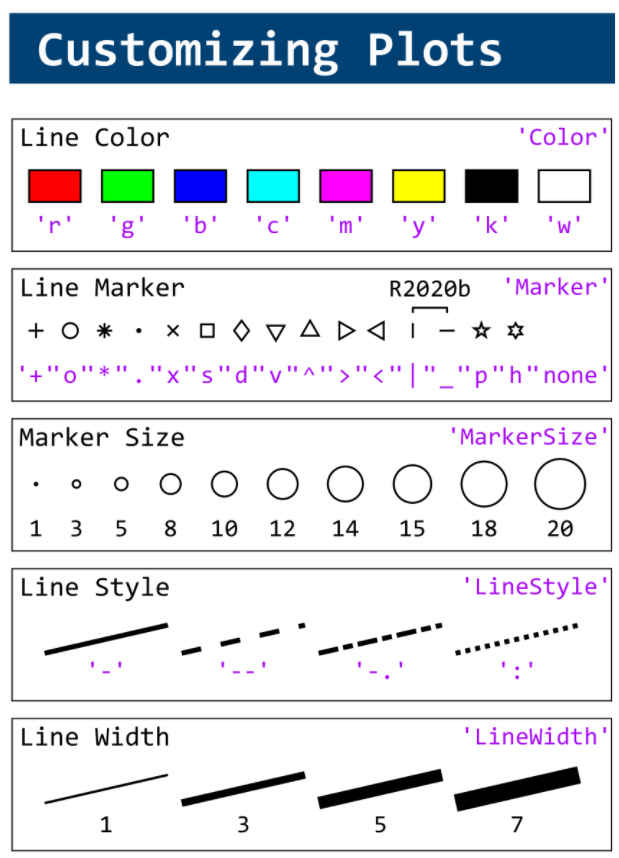

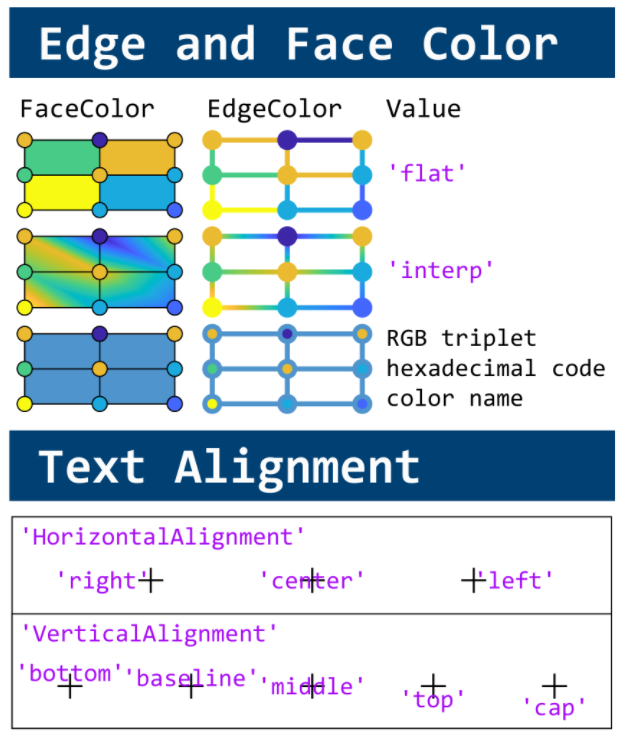

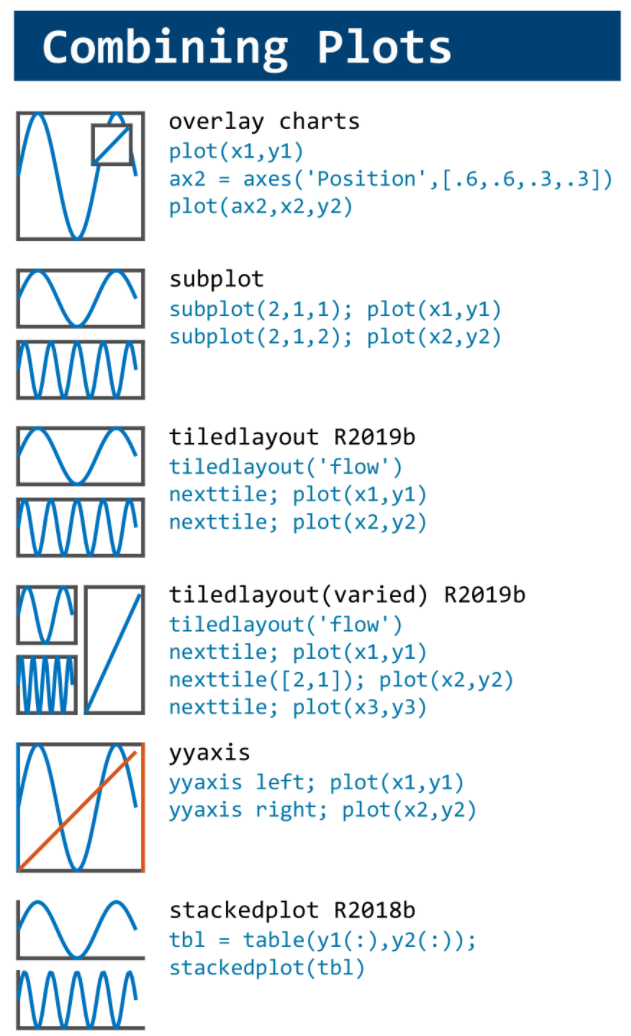

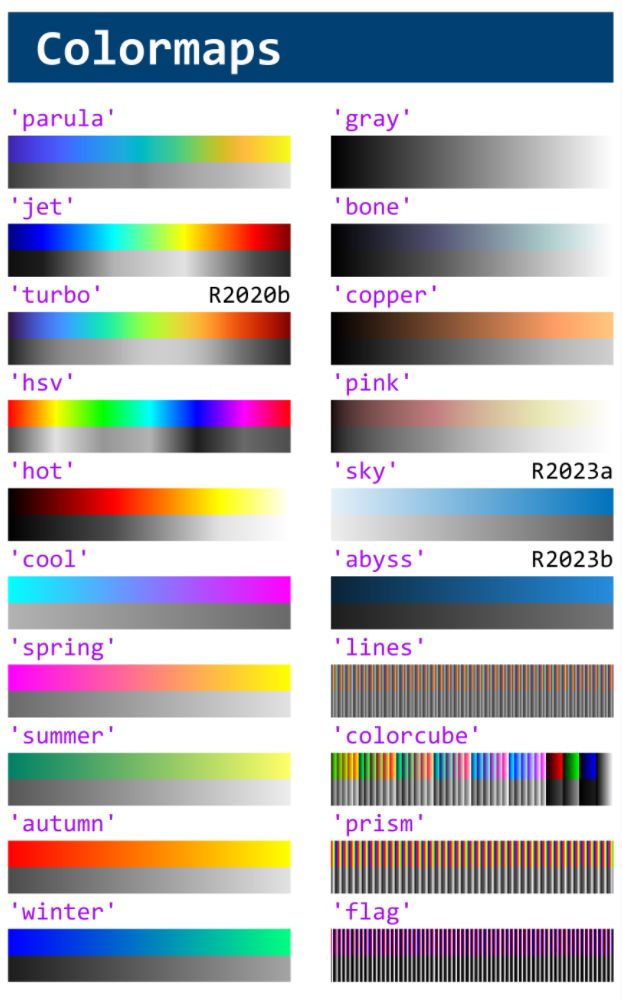

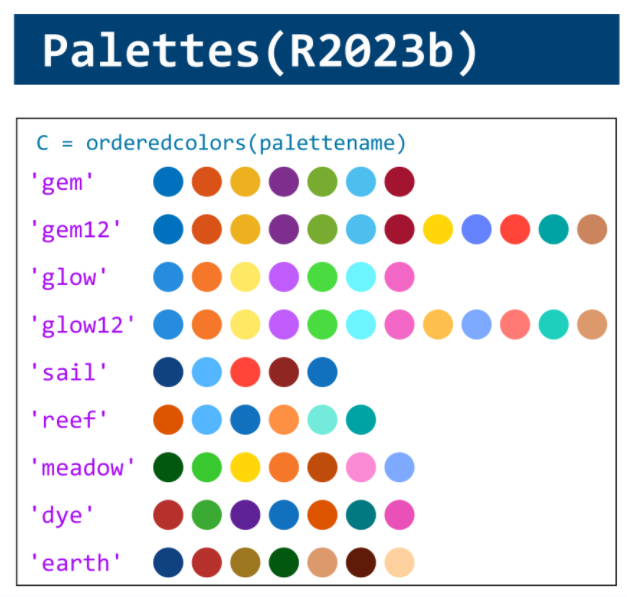

This cheat sheet is here:

reference:

- https://github.com/peijin94/matlabPlotCheatsheet

- https://github.com/mathworks/visualization-cheat-sheet

- https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab/plot-gallery.html

- https://www.mathworks.com/help/matlab/release-notes.html

MATLAB used to have official visualization-cheat-sheet, but there have been quite a few new updates in MATLAB versions recently. Therefore, I made my own cheat sheet and marked the versions of each new thing that were released :

Hi to all.

I'm trying to learn a bit about trading with cryptovalues. At the moment I'm using Freqtrade (in dry-run mode of course) for automatic trading. The tool is written in python and it allows to create custom strategies in python classes and then run them.

I've written some strategy just to learn how to do, but now I'd like to create some interesting algorithm. I've a matlab license, and I'd like to know what are suggested tollboxes for following work:

- Create a criptocurrency strategy algorythm (for buying and selling some crypto like BTC, ETH etc).

- Backtesting the strategy with historical data (I've a bunch of json files with different timeframes, downloaded with freqtrade from binance).

- Optimize the strategy given some parameters (they can be numeric, like ROI, some kind of enumeration, like "selltype" and so on).

- Convert the strategy algorithm in python, so I can use it with Freqtrade without worrying of manually copying formulas and parameters that's error prone.

- I'd like to write both classic algorithm and some deep neural one, that try to find best strategy with little neural network (they should run on my pc with 32gb of ram and a 3080RTX if it can be gpu accelerated).

What do you suggest?

Dear MATLAB contest enthusiasts,

I believe many of you have been captivated by the innovative entries from Zhaoxu Liu / slanderer, in the 2023 MATLAB Flipbook Mini Hack contest.

Ever wondered about the person behind these creative entries? What drives a MATLAB user to such levels of skill? And what inspired his participation in the contest? We were just as curious as you are!

We were delighted to catch up with him and learn more about his use of MATLAB. The interview has recently been published in MathWorks Blogs. For an in-depth look into his insights and experiences, be sure to read our latest blog post: Community Q&A – Zhaoxu Liu.

But the conversation doesn't end here! Who would you like to see featured in our next interview? Drop their name in the comments section below and let us know who we should reach out to next!

The study of the dynamics of the discrete Klein - Gordon equation (DKG) with friction is given by the equation :

above equation, W describes the potential function :

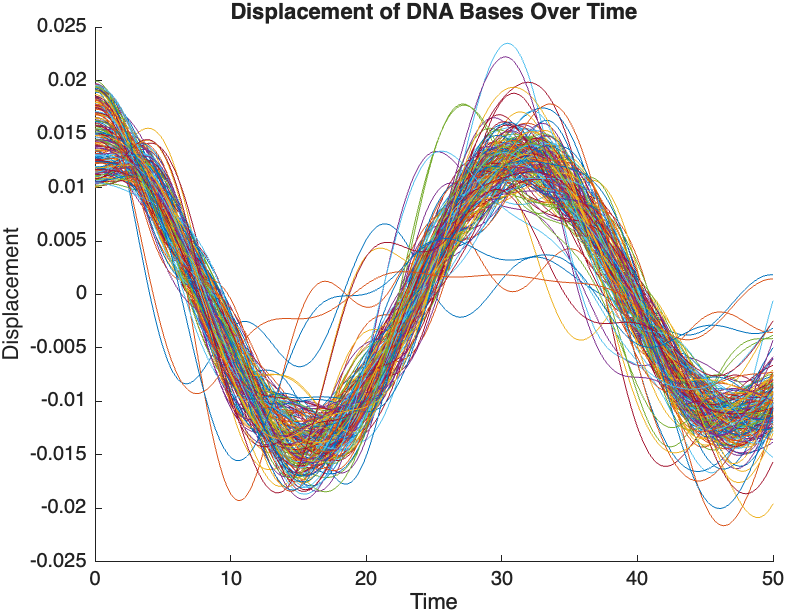

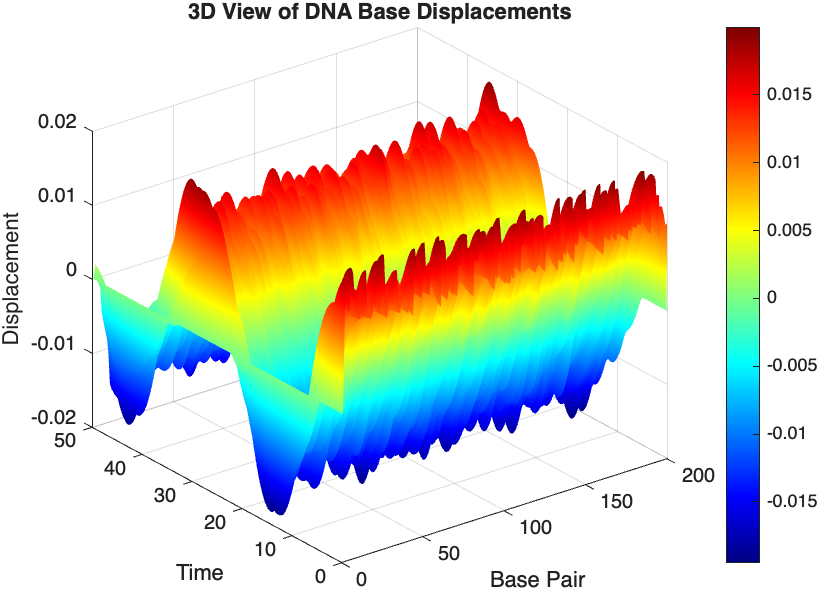

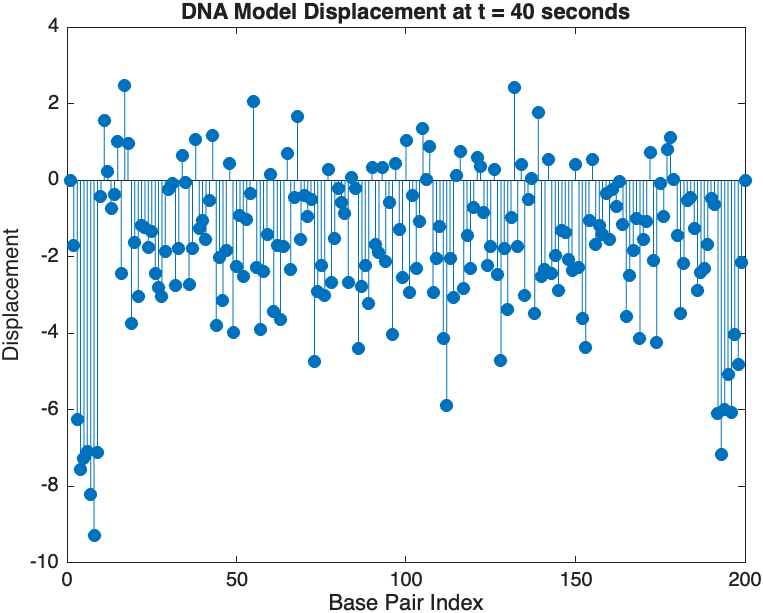

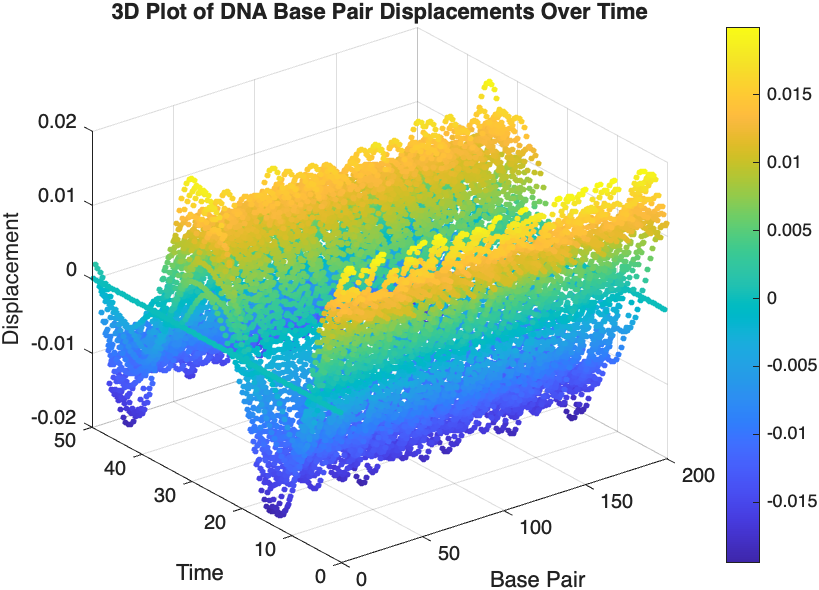

The objective of this simulation is to model the dynamics of a segment of DNA under thermal fluctuations with fixed boundaries using a modified discrete Klein-Gordon equation. The model incorporates elasticity, nonlinearity, and damping to provide insights into the mechanical behavior of DNA under various conditions.

% Parameters

numBases = 200; % Number of base pairs, representing a segment of DNA

kappa = 0.1; % Elasticity constant

omegaD = 0.2; % Frequency term

beta = 0.05; % Nonlinearity coefficient

delta = 0.01; % Damping coefficient

- Position: Random initial perturbations between 0.01 and 0.02 to simulate the thermal fluctuations at the start.

- Velocity: All bases start from rest, assuming no initial movement except for the thermal perturbations.

% Random initial perturbations to simulate thermal fluctuations

initialPositions = 0.01 + (0.02-0.01).*rand(numBases,1);

initialVelocities = zeros(numBases,1); % Assuming initial rest state

The simulation uses fixed ends to model the DNA segment being anchored at both ends, which is typical in experimental setups for studying DNA mechanics. The equations of motion for each base are derived from a modified discrete Klein-Gordon equation with the inclusion of damping:

% Define the differential equations

dt = 0.05; % Time step

tmax = 50; % Maximum time

tspan = 0:dt:tmax; % Time vector

x = zeros(numBases, length(tspan)); % Displacement matrix

x(:,1) = initialPositions; % Initial positions

% Velocity-Verlet algorithm for numerical integration

for i = 2:length(tspan)

% Compute acceleration for internal bases

acceleration = zeros(numBases,1);

for n = 2:numBases-1

acceleration(n) = kappa * (x(n+1, i-1) - 2 * x(n, i-1) + x(n-1, i-1)) ...

- delta * initialVelocities(n) - omegaD^2 * (x(n, i-1) - beta * x(n, i-1)^3);

end

% positions for internal bases

x(2:numBases-1, i) = x(2:numBases-1, i-1) + dt * initialVelocities(2:numBases-1) ...

+ 0.5 * dt^2 * acceleration(2:numBases-1);

% velocities using new accelerations

newAcceleration = zeros(numBases,1);

for n = 2:numBases-1

newAcceleration(n) = kappa * (x(n+1, i) - 2 * x(n, i) + x(n-1, i)) ...

- delta * initialVelocities(n) - omegaD^2 * (x(n, i) - beta * x(n, i)^3);

end

initialVelocities(2:numBases-1) = initialVelocities(2:numBases-1) + 0.5 * dt * (acceleration(2:numBases-1) + newAcceleration(2:numBases-1));

end

% Visualization of displacement over time for each base pair

figure;

hold on;

for n = 2:numBases-1

plot(tspan, x(n, :));

end

xlabel('Time');

ylabel('Displacement');

legend(arrayfun(@(n) ['Base ' num2str(n)], 2:numBases-1, 'UniformOutput', false));

title('Displacement of DNA Bases Over Time');

hold off;

The results are visualized using a plot that shows the displacements of each base over time . Key observations from the simulation include :

- Wave Propagation: The initial perturbations lead to wave-like dynamics along the segment, with visible propagation and reflection at the boundaries.

- Damping Effects: The inclusion of damping leads to a gradual reduction in the amplitude of the oscillations, indicating energy dissipation over time.

- Nonlinear Behavior: The nonlinear term influences the response, potentially stabilizing the system against large displacements or leading to complex dynamic patterns.

% 3D plot for displacement

figure;

[X, T] = meshgrid(1:numBases, tspan);

surf(X', T', x);

xlabel('Base Pair');

ylabel('Time');

zlabel('Displacement');

title('3D View of DNA Base Displacements');

colormap('jet');

shading interp;

colorbar; % Adds a color bar to indicate displacement magnitude

% Snapshot visualization at a specific time

snapshotTime = 40; % Desired time for the snapshot

[~, snapshotIndex] = min(abs(tspan - snapshotTime)); % Find closest index

snapshotSolution = x(:, snapshotIndex); % Extract displacement at the snapshot time

% Plotting the snapshot

figure;

stem(1:numBases, snapshotSolution, 'filled'); % Discrete plot using stem

title(sprintf('DNA Model Displacement at t = %d seconds', snapshotTime));

xlabel('Base Pair Index');

ylabel('Displacement');

% Time vector for detailed sampling

tDetailed = 0:0.5:50; % Detailed time steps

% Initialize an empty array to hold the data

data = [];

% Generate the data for 3D plotting

for i = 1:numBases

% Interpolate to get detailed solution data for each base pair

detailedSolution = interp1(tspan, x(i, :), tDetailed);

% Concatenate the current base pair's data to the main data array

data = [data; repmat(i, length(tDetailed), 1), tDetailed', detailedSolution'];

end

% 3D Plot

figure;

scatter3(data(:,1), data(:,2), data(:,3), 10, data(:,3), 'filled');

xlabel('Base Pair');

ylabel('Time');

zlabel('Displacement');

title('3D Plot of DNA Base Pair Displacements Over Time');

colorbar; % Adds a color bar to indicate displacement magnitude

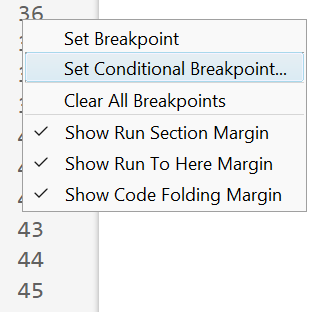

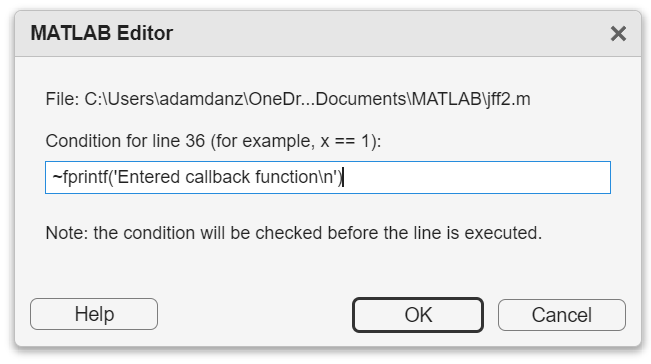

Temporary print statements are often helpful during debugging but it's easy to forget to remove the statements or sometimes you may not have writing privileges for the file. This tip uses conditional breakpoints to add print statements without ever editing the file!

What are conditional breakpoints?

Conditional breakpoints allow you to write a conditional statement that is executed when the selected line is hit and if the condition returns true, MATLAB pauses at that line. Otherwise, it continues.

The Hack: use ~fprintf() as the condition

fprintf prints information to the command window and returns the size of the message in bytes. The message size will always be greater than 0 which will always evaluate as true when converted to logical. Therefore, by negating an fprintf statement within a conditional breakpoint, the fprintf command will execute, print to the command window, and evalute as false which means the execution will continue uninterupted!

How to set a conditional break point

1. Right click the line number where you want the condition to be evaluated and select "Set Conditional Breakpoint"

2. Enter a valid MATLAB expression that returns a logical scalar value in the editor dialog.

Handy one-liners

Check if a line is reached: Don't forget the negation (~) and the line break (\n)!

~fprintf('Entered callback function\n')

Display the call stack from the break point line: one of my favorites!

~fprintf('%s\n',formattedDisplayText(struct2table(dbstack)))

Inspect variable values: For scalar values,

~fprintf('v = %.5f\n', v)

~fprintf('%s\n', formattedDisplayText(v)).

Make sense of frequent hits: In some situations such as responses to listeners or interactive callbacks, a line can be executed 100s of times per second. Incorporate a timestamp to differentiate messages during rapid execution.

~fprintf('WindowButtonDownFcn - %s\n', datetime('now'))

Closing

This tip not only keeps your code clean but also offers a dynamic way to monitor code execution and variable states without permanent modifications. Interested in digging deeper? @Steve Eddins takes this tip to the next level with his Code Trace for MATLAB tool available on the File Exchange (read more).

Summary animation

To reproduce the events in this animation:

% buttonDownFcnDemo.m

fig = figure();

tcl = tiledlayout(4,4,'TileSpacing','compact');

for i = 1:16

ax = nexttile(tcl);

title(ax,"#"+string(i))

ax.ButtonDownFcn = @axesButtonDownFcn;

xlim(ax,[-1 1])

ylim(ax,[-1,1])

hold(ax,'on')

end

function axesButtonDownFcn(obj,event)

colors = lines(16);

plot(obj,event.IntersectionPoint(1),event.IntersectionPoint(2),...

'ko','MarkerFaceColor',colors(obj.Layout.Tile,:))

end